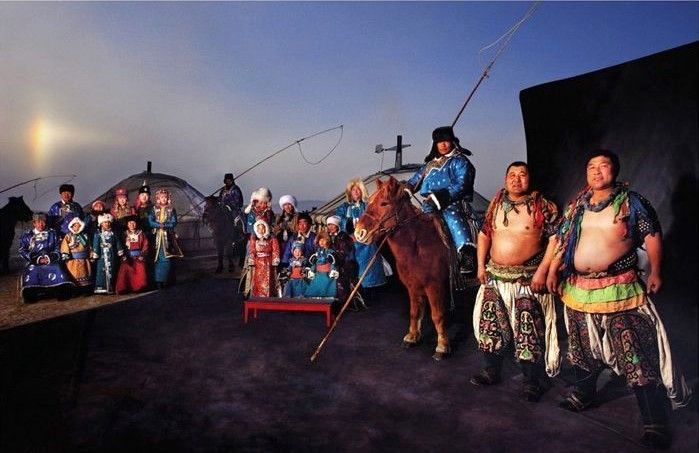

The festivals of the Mongolian people are lavish and lively affairs, resplendent with fine banquets, rugged horse-racing, archery competitions, heated bouts of wrestling, and animated performances of singing and dancing. They are the ideal forum to learn more about their vibrant nomadic culture, from their dairy-based cuisine and colourful traditional clothes to their unparalleled horsemanship and poignant respect for the natural world.

The Ovoo Worship Ceremony

The Mongols follow their own folk religion known as Mongolian shamanism and, within this faith, ovoos are sacred stone heaps made from nearby rocks, wood, and strips of colourful silk. They function as sacrificial altars and are each representative of a different deity in the religion’s pantheon. From May to August, grand worship ceremonies will take place at different ovoos throughout Inner Mongolia, when the grasslands are carpeted with jade and wild flowers are in full bloom. It serves as a forerunner to the Naadam Festival in late August, and focuses primarily on ancestor worship, nature worship, and hero worship.

Herdsmen will travel from far-flung settlements and congregate at an ovoo, where they will make sacrificial offerings of meat, dairy products, and alcohol. Within the ceremony, there are four different categories of worship: Blood Worship, Wine Worship, Fire Worship, and Jade Worship. The Mongols believe that all livestock is a gift from the gods, so blood worship involves slaughtering a horse or lamb in front of the ovoo as a way to repay the gods’ benevolence and generosity. Wine worship entails pouring libations of fresh milk and mare’s milk wine onto the ovoo.

The most unusual of all is arguably fire worship, where Mongols throw well-cooked beef or mutton into a bonfire while whispering their family names in the hopes of dispelling evil forces. Jade worship is more of an antiquated pastime, where Mongolian nobles would place expensive jade items onto the ovoo as offerings. Nowadays, cheaper substitutes such as coins, fried rice, and pearls are used.

The bulk of the ceremony consists of a Buddhist lama chanting sutras and carrying out a variety of important rituals, such as burning incense and pouring libations onto the ovoo. Once the lama is finished, the participants will circle around the ovoo three times while praying for good fortune and longevity. At this point, it’s time for the ovoo to receive a much needed facelift! Its silk banners are replaced and new rocks are added to revive its stately and spiritual appearance. After the sombre religious rituals are over, the real festivities begin! Potent milk wine flows, banquets are plentiful, locals chat happily, horse races tear up the earth, and young people seize the opportunity to search for a sweetheart.

The Naadam Festival

Like Spring Festival to the Han Chinese, the Naadam Festival is the most important holiday in the Mongolian calendar and is designed to celebrate the yearly harvest. It dates all the way back to the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368) and is celebrated annually in late August for between five to seven days. The name Naadam, which is short for “Eriyn Gurvan Naadam” or the “Three Manly Games”, is a reference to horse racing, archery, and wrestling, which are the three main events that the festival revolves around. However, performances of singing, dancing, and even a livestock fair also form a significant part of the festivities. The largest Naadam Festival is held in Ulaanbaatar, the capital of Mongolia, although grand festivals are still held throughout Inner Mongolia, Xinjiang, Gansu province, and Qinghai province as well.

Winners of the festival competitions are granted prizes of silk scarves and livestock, and are regarded as local heroes, so the stakes are high! Much like the Olympics, the festivities begin with a vibrant parade of participating athletes, horse riders, monks, musicians, and dancers, all decked out in their colourful traditional clothes. The size of each competitive event depends upon the size of the festival itself. Small-sized festivals only attract between 60 to 120 wrestlers and 30 to 50 horse riders; medium-sized ones boast around 250 wrestlers and 100 to 150 riders; and larger festivals can have upwards of 500 wrestlers and 300 riders!

Wrestling, which is usually the first event of the festival, is held in high regard by the Mongolian people as a test of strength, intelligence, and tactics. The wrestling contest has no weight classes and is a single-elimination tournament that lasts roughly nine to ten rounds. The only rule is that the number of participants must be divisible by two. The participants must wear a traditional costume comprised of a tight leather shoulder vest, a pair of shorts, special leather boots, and a colourful silk ribbon tied around their neck. This leaves their chest bare, thus proving that the wrestler is male. According to legend, it was said that long ago many men were defeated by a single woman, and this is why the wrestling costume now must expose the chest. You could almost say that they have to keep abreast of the competition!

Mongolian wrestling is made up of thirteen basic skills, including pushing, pressing, and pulling. You are permitted to grab the shoulder, hold the waist, or grasp your opponent’s clothes, but you cannot hold your opponent’s legs, hit his face, pull his hair, kick him above the knees, or get behind his back and push him over. In order to win, you have to force your opponent to touch the ground with his upper body or elbow.

The top wrestlers are awarded one of the following six titles: Falcon, Hawk, Elephant, Garuda, Lion, and Titan. Any wrestler who defeated five opponents is a Falcon; six wins grants you the title of Hawk; an Elephant is anyone who won seven or eight matches; the mighty Garuda will have toppled eight or nine opponents; and the Lion is the ultimate winner of the entire competition. Anyone who wins the national wrestling competition more than once is granted the enviable title of Titan.

Archery follows the wrestling contest, and enjoys a venerable history in Mongolian culture. Since ancient times, bows and arrows have been the primary weapons of the Mongolian people, either to hunt animals or to fight in tribe wars. Nowadays they are mainly used recreationally, but remain a symbol of the Mongols’ enduring legacy as formidable warriors.

The archery contest itself falls into three categories: field archery, archery on horseback, and long distance archery. Unlike wrestling, participants of all ages and genders are allowed to take part in the archery contests. They must bring their own bows and arrows, although there are no restrictions on the style, tension, length, or weight of their equipment. There are 3 rounds, with each participant shooting 3 arrows per round. The one who hits the target most often is the winner. It’s as simple as that!

Much like archery, the horse riding falls into three categories: the speed contest, the pace contest, and the acrobatic contest. The speed contest is a simple distance race, the pace contest is much like modern-day dressage, and the acrobatic contest is based on spectacular acrobatic manoeuvres performed on horseback. Typically children between the ages of 6 and 13 compete in the horse riding contests. Talk about starting them young!

Historically, the ancestors of the Mongols were small nomadic tribes, such as the Xiongnu, the Xianbei, and the Donghu, who roamed the regions surrounding the Argun River sometime between the 5th and 3rd century BC. They remained largely separate until the beginning of the 13th century, when an enigmatic warrior loomed on the horizon and threatened to irrevocably change the course of history.

Historically, the ancestors of the Mongols were small nomadic tribes, such as the Xiongnu, the Xianbei, and the Donghu, who roamed the regions surrounding the Argun River sometime between the 5th and 3rd century BC. They remained largely separate until the beginning of the 13th century, when an enigmatic warrior loomed on the horizon and threatened to irrevocably change the course of history.