(960–1127)

Like many rulers before him, Zhao Kuangyin began his political career under the service of others. He was a militarist working for the Later Zhou Dynasty (951–960), which controlled China’s northern territories during a chaotic era known as the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms Period (907-960). The country had been fractured into a number of warring regimes, with five dynasties ruling consecutively in the north and ten kingdoms dominating the south and west. When Emperor Shizong suddenly died, he was succeeded by a seven-year-old boy and the Later Zhou weakened further.

In 960, Zhao decided to seize this valuable opportunity and usurped the throne, establishing himself as Emperor Taizu of the Song Dynasty. He was a staunch believer in Confucian ideals and, as such, he made the decision to live modestly, listen to his advisors carefully, and curb excessive taxation. News quickly spread of his benevolence and the Song Dynasty rose in prestige. Although he commanded a formidable army, he decided to employ diplomacy when it came to vanquishing his rivals. Rather than face weathered military generals in battle, he offered them honorary titles, cushy government jobs, and generous pensions in exchange for their allegiance. Never before had an emperor employed such a political strategy in Chinese history.

This expert political manoeuvring, coupled with well-planned military strategies, led Taizu to slowly but surely annex many of his rival kingdoms. During his reign, he also promoted the use of the imperial examinations to select officials based on skill and merit, rather than social standing or military position. This set the standard for the rest of the dynasty, and eventually resulted in the imperial government transforming from an aristocratic entity into a bureaucratic one.

On his untimely death in 976, he was succeeded by his younger brother, Emperor Taizong, who decided to finish what his sibling had started. After all, you’ve got to uphold your family values! Taizong turned his attention northward and conquered the last of the Ten Kingdoms, the Kingdom of Northern Han (951–979). Thus China was finally unified under Song rule. However, it seemed that Taizong allowed this victory to go to his head! During this time, the Song faced two major enemies on their borders: the Khitans of the Liao Dynasty (907–1125) in the northeast and the Tanguts of the Western Xia Dynasty (1038–1227) to the northwest.

Taizong embarked on a campaign to dominate the Liao and retrieve an area known as the Sixteen Prefectures, which belonged to the Liao but was traditionally considered part of China proper. His attempts culminated in a disastrous defeat in 986. After several more brutal clashes, his successor, Emperor Zhenzong, arranged the signing of the Chanyuan Treaty in 1005, which assured a peaceful co-existence between the two regimes on the proviso that the Song provide a yearly tribute to the Liao and recognise them as peers. Considering the economic prosperity of the Song, it was a small price to pay for security.

By this time, the bureaucracy had developed from a simplistic system into a well-oiled machine. The imperial examinations were well-regulated and led to the appointment of several excellent scholar-officials. It was these talented men who came to dominate the higher levels of policy-making in government. However, many members of this educated elite staunchly upheld Confucian ideals, and this frequently caused tension between them and the aristocracy. They were highly critical of palace impropriety, corruption, sluggishness, and social inequality within the realm. Long-standing officials from the north, who often had aristocratic family backgrounds, resolutely opposed these “newcomers”. However, it appeared that the complaints of the new officials were justified, as peace and prosperity within the regime gradually began to erode.

Small-scale rebellions broke out near the capital, and the Western Xia Dynasty suddenly renounced its vassal status, declaring its independence. Meanwhile, the Liao Dynasty threatened another invasion, which was only staved off when the Song increased its yearly tribute. On the surface, the system seemed stable, but it was rapidly deteriorating. Military expenditures and a costly, expanding bureaucracy meant that palace income no longer covered expenses. By the time Emperor Yingzong took the throne in 1063, the government was embroiled in a series of minor disputes that resulted in severe schisms.

But it seems the worst was yet to come! Yingzong’s successor, Emperor Shenzong, is often bemoaned for ending the Song’s golden age of effective governance. His response to the bureaucratic crisis was to make the scholar-poet Wang Anshi his chief councillor and bestow upon him inordinate political power. Wang’s reforms, known as the New Laws or New Policies, attempted to drastically change the established institution. The main aim was to streamline the administration, increase the empire’s fiscal intake, and improve the Song’s military strength. Wang was nothing if not ambitious!

To this end, he finally acknowledged the rapidly spreading money economy by prompting the state to increase the supply of currency, become involved in trading, and stabilise prices whenever and wherever it was deemed necessary. In this way, the imperial court was able to make a commercial profit. A number of other reforms, such as maintaining emergency granaries and employing a graduated tax system based on individual income, were designed to relieve the financial burden of China’s citizens. It seemed that, in many ways, Wang was on the right track to achieving his ideal.

However, this gigantic reform program required an energetic bureaucracy, one which Wang attempted to create with limited success. He promoted a nationwide school system; demoted or dismissed uncooperative officials; and provided strong incentives, such as promotions, for members of the administration who improved their performance. Although his intentions may have been for the greater good, Wang’s reform program was met with bitter opposition. His policies hurt the interests of several key social groups, including large landowners, powerful merchants, and moneylenders. The bulk of government officials, who came from these wealthy classes, were deliberately rebellious or openly attempted to sabotage his plans.

Both Shenzong and Wang failed to acknowledge the fact that the administrative system, which had become deeply entrenched by that time, simply couldn’t tolerate such radical change. Many of their reforms concentrated power at the top, expanded the government’s influence in society, and applied policies uniformly to a uniquely diverse empire. Many of Wang’s opponents argued against these reforms based on Confucian principles, claiming it was inappropriate for the state to pursue profits, assume inordinate political power, and excessively interfere in the lives of its people.

While Wang claimed the reforms would bring about social equality, stability, and an end to corruption, they ended up doing just the opposite. Unscrupulous officials were able to exploit the system to their advantage, factional strife within the court was at an all-time high, and the country’s population suffered intensely. The Song Dynasty, which was once famed for its “art of governance”, was slowly starting to unravel.

The situation became still more confused when Shenzong passed away. The reforms were repealed by the Empress Dowager, only to be swiftly re-established by Emperor Zhezong. When Zhezong’s heir, Emperor Huizong, took the throne, the situation only worsened. Although Huizong was a patron of the arts and a phenomenal artist himself, he was incredibly self-indulgent and irresponsible when it came to matters of state. His extravagant spending pushed the imperial treasury ever closer towards bankruptcy.

More serious still was Huizong’s carelessness when it came to foreign policy. He chose to disregard the treaty that the Song held with the Liao Dynasty and instead allied with the formidable Jurchen people, who sought to expand their empire. Eventually, they were able to conquer the Liao and established the Jin Dynasty[1] (1115–1234) in its stead. However, the Jurchens had done much of the fighting and accused the Song of not holding up their end of the deal. The alliance between them quickly soured and the Jin-Song Wars (1125–1234) began.

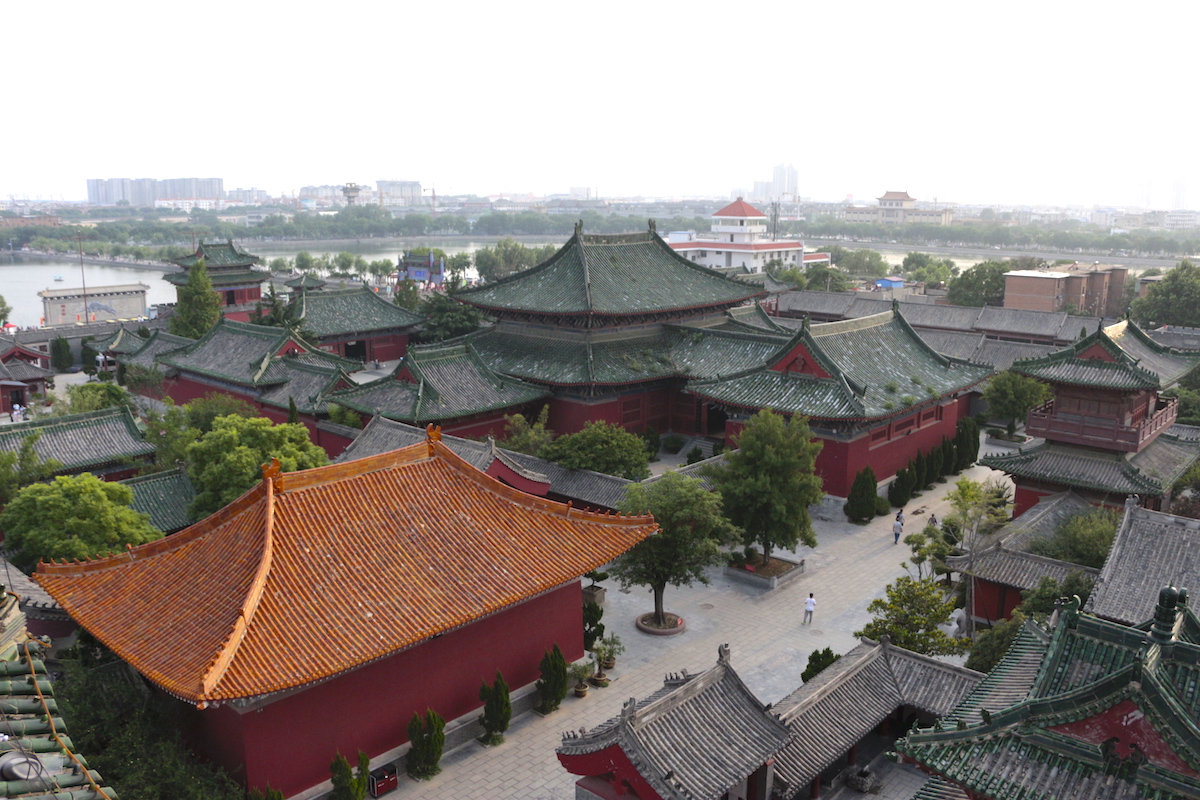

At this inopportune moment, Huizong chose to abdicate and placed his unprepared son, Emperor Qinzong, on the throne. Corruption ran rife throughout the imperial court and the administration became increasingly ineffective, making the Song easy prey for the Jurchens. In 1127, they laid siege to the imperial capital of Bianjing (modern-day Kaifeng) and demanded extortionate ransoms from the imperial court.

When they became aware that local resources were nearly exhausted, the invaders changed their tactics. They captured Huizong, Qinzong, and much of the imperial family, exiled them to Manchuria, and took control of China’s northern territories. This put a tragic end to the Northern Song Dynasty, but it wasn’t about to go out without a fight! The Jurchens had failed to capture one of Huizong’s sons, who fled south to Lin’an (modern-day Hangzhou) and established the Southern Song Dynasty (1127–1279) under the title Emperor Gaozong.

[1] This is often referred to as the Jurchen Jin Dynasty to avoid confusion with dynasties of the same name.