In 1900, after yet another humiliating defeat by foreign powers, the Qing Dynasty was on the brink of collapse and revolutionary thought was spreading across China. The imperial treasury was crippled with debt, peasant uprisings wreaked havoc throughout the country, and foreign countries continued to impose their excessive demands on the administration. In 1908, the reigning Guangxu Emperor was fatally poisoned and, just a day later, the infamous Empress Dowager Cixi also passed away. She had long held a political stranglehold on the imperial court, and her death left a power vacuum in the Qing government.

On her deathbed, Cixi chose a boy named Puyi to succeed as emperor, in spite of the fact that he was only two years old at the time. Puyi’s father Zaifeng (Prince Chun) was made regent, while the formidable military general Yuan Shikai was dismissed from his position of power. Before the deaths of Guangxu and Cixi, many members of the upper class had been demanding that a constitutional government be instituted. Although Zaifeng created a committee of thirteen senior ministers to aid him, five of them were members of the imperial family and this caused outrage among the people.

Meanwhile, a commoner called Sun Yat-sen was rising to prominence. He had been educated in Western-style schools in Hawaii and Hong Kong, and thus had no background in Confucian orthodoxy. In 1894, he travelled to Tianjin to meet with a high-ranking official and present his radical reform program, but he was refused an interview. This event sparked an anti-dynastic attitude that would eventually change the course of Chinese history. As a result, Sun formed a secret society of revolutionaries known as the Revive China Society.

After an abortive attempt to capture Guangzhou in 1895, Sun fled to Hong Kong and then went on to Japan, where he soon garnered a flock of dedicated followers. Many of his supporters were disillusioned Chinese youths who were studying abroad in Japan. They faced competition from former Qing officials such as Kang Youwei and Liang Qichao, who had also fled to Japan and took a reformist rather than a revolutionary stance. The two camps vied for funds and secret-society members on the mainland. Unfortunately, Sun would be forced to flee from Japan later that year and stopped off in Hawaii before finally ending up in the UK. He didn’t leave the UK until 1897, when he visited Canada and eventually returned to Japan.

Sun’s party enjoyed a major victory when they managed to secure the alliance of an influential secret society from the mainland called the Society of Brothers and Elders. Together, they formed the Revive Han Association and nominated Sun as their leader. In 1900, they started an uprising in Guangdong province, but it ended after just two weeks of fighting. Though it may have failed, Sun’s movement clearly ignited a spark in the Chinese people, as revolutionary organisations such as the Chinese Educational Association and the Restoration Society began appearing in Shanghai not long thereafter.

Many of Sun’s original followers had been uneducated, and he was by no means a master of political philosophy. Thus, he found it challenging to manage the new young intellectuals who were joining his ranks in droves. His response came in the form of the Three Principles of the People: Nationalism, Democracy, and Socialism. From 1903 to 1905, he travelled across America and Europe expounding his philosophy before finally returning to Tokyo, where he was invited by activists to become the leader of a new organisation called the United League.

Unfortunately, the League soon fell into disharmony, as some followers denounced Sun’s Three Principles, while others simply turned to anarchism. Meanwhile, in mainland China, a very different crisis was unfolding. In 1905, China managed to retrieve the Hankou-Guangzhou railway line from the American China Development Company, and this prompted a nationwide desire for railway expansion. However, year after year railway construction was delayed because the imperial treasury was unable to raise enough capital.

To combat this problem, the Qing court decided to nationalise some important railway lines in the hopes that they would attract foreign investment. In 1911, the Hankou-Guangzhou and Sichuan-Hankou lines were nationalised and a loan contract was signed with the four-power banking consortium (bankers of Britain, France, Germany, and the United States). This incensed the Sichuan gentry, merchants, and landlords, who had invested large sums of money in the Sichuan-Hankou line. Soon the situation escalated into a province-wide uprising. While some troops from Hubei province were dispatched to quell the revolt, many of them chose to mutiny instead.

On October 10th, these rebel troops occupied the provincial capital of Wuchang (modern-day Wuhan), and this came to be known as the memorial day of the Chinese Revolution (1911-1912). The success of these rebels triggered numerous supportive uprisings in important cities throughout central and southern China. Although the constitutionalist movement had originally been anti-revolutionary, they soon followed suit and coerced their provincial governments into declaring their provinces independent of Qing rule.

With the uprisings swiftly spiralling out of control, the Qing government was forced to recall General Yuan Shikai from retirement, along with the dedicated New Army that he commanded. However, Yuan had other plans! While he deprived the Qing government of its most powerful army, he simultaneously began negotiating with the revolutionaries. Towards the end of 1911, Yuan’s emissaries and the revolutionary representatives had agreed that the Qing Emperor must abdicate, and that a National Assembly would be formed to decide whether Yuan should become the president of the new republic.

Yuan’s plan seemingly backfired when the presidency was awarded to Sun Yat-sen instead. However, Yuan finally came to an agreement with Empress Dowager Longyu that the Qing emperor would step down if Yuan was made president. Feeling that his life’s work was accomplished and that the republic was in safe hands, Sun voluntarily resigned in February 1912, the child emperor Puyi abdicated, and Yuan became the President of the Republic of China. After 268 years, the Qing Dynasty finally came to an end. Yet, far more significantly, this event marked the end of over 2,000 years of imperial rule in China.

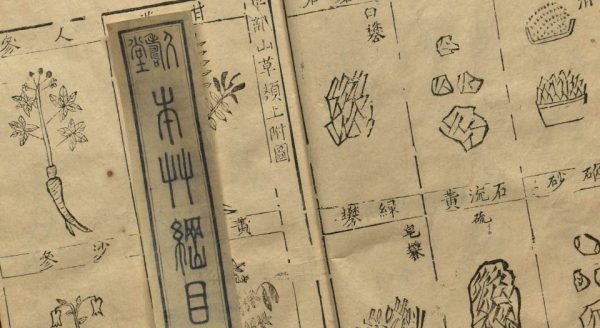

While writers and philosophers were striking out in bold new directions, artists and artisans weren’t far behind. The Ming Dynasty has long been esteemed for the diversity and quality of its crafted wares, particularly with reference to cloisonné and porcelain. The most famous of these is the iconic blue-and-white porcelain, which was a hot commodity in Europe at the time. When it came to painting, the style of the time was greatly influenced by the Four Masters of the Wu School: Shen Zhou, Qiu Ying, Tang Yin, and Wen Zhengming. They were the most highly esteemed artists of their age, and their work prompted a movement away from the academic, instead placing emphasis on individualistic self-expression and technical excellence.

While writers and philosophers were striking out in bold new directions, artists and artisans weren’t far behind. The Ming Dynasty has long been esteemed for the diversity and quality of its crafted wares, particularly with reference to cloisonné and porcelain. The most famous of these is the iconic blue-and-white porcelain, which was a hot commodity in Europe at the time. When it came to painting, the style of the time was greatly influenced by the Four Masters of the Wu School: Shen Zhou, Qiu Ying, Tang Yin, and Wen Zhengming. They were the most highly esteemed artists of their age, and their work prompted a movement away from the academic, instead placing emphasis on individualistic self-expression and technical excellence. This made life particularly difficult for the Christian missionaries who had travelled from Europe to China. It was only when Matteo Ricci, a Jesuit who spoke fluent Chinese and was well-acquainted with Confucian principles, arrived in 1583 that the reputation of European foreigners began to change. By the time of his death in 1610, a handful of Chinese officials had converted to Christianity, and Jesuit communities could be found throughout central and southern China. In fact, he was held in such high regard that the Emperor even allowed his remains to be buried in Beijing and eventually other missionaries would be buried in the same spot, which came to be known as the Zhalan Cemetery. It was these Jesuits who produced a number of books in Chinese about European science and theology. Although their effect was quite limited, European technology and ideas were beginning to take hold in China towards the end of the Ming Dynasty.

This made life particularly difficult for the Christian missionaries who had travelled from Europe to China. It was only when Matteo Ricci, a Jesuit who spoke fluent Chinese and was well-acquainted with Confucian principles, arrived in 1583 that the reputation of European foreigners began to change. By the time of his death in 1610, a handful of Chinese officials had converted to Christianity, and Jesuit communities could be found throughout central and southern China. In fact, he was held in such high regard that the Emperor even allowed his remains to be buried in Beijing and eventually other missionaries would be buried in the same spot, which came to be known as the Zhalan Cemetery. It was these Jesuits who produced a number of books in Chinese about European science and theology. Although their effect was quite limited, European technology and ideas were beginning to take hold in China towards the end of the Ming Dynasty.