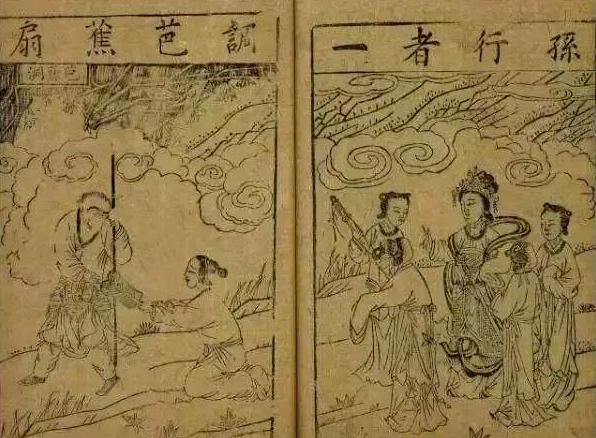

Considering how strict and dictatorial the Ming Dynasty was, it would seem surprising that any creative expression would be possible in such an oppressive environment. Yet it was during this time that three of the Four Great Classical Novels of Chinese literature were penned: Journey to the West, Romance of the Three Kingdoms, and The Water Margin. To this day, these historic works are highly revered and have exerted considerable influence on modern Chinese culture.

While the scholarly elite were educated enough to fully comprehend and appreciate Classical Chinese, the Ming Dynasty saw the rise of a large audience with a rudimentary but functional education, who were eager to devour any literary works written in vernacular Chinese. Although this type of colloquial fiction had been popular since the Tang Dynasty (618-907), it didn’t fully blossom until the Ming. It was during this time that some of the true masterpieces of popular fiction were created. Superlative theatrical works, such as The Peony Pavilion, also enjoyed great popularity.

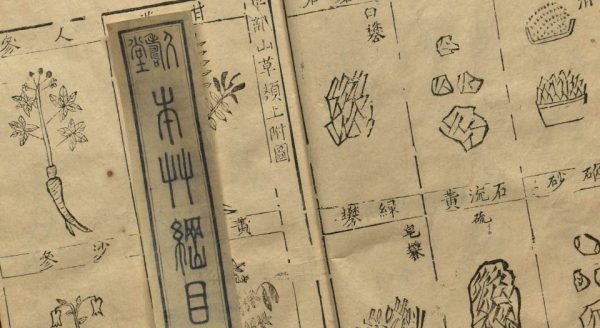

Yet Ming literature wasn’t solely confined to the realms of the spectacular and the fantastical! In many ways, Ming literati were some of the most prolific when it came to creating and preserving works of sober scholarship. Great private libraries were founded, such as the famed Tianyige Collection of the Fan family, and huge anthologies of rare books were published in order to save them from extinction. Scholars produced stunning illustrated encyclopaedias on topics innumerable; from the Bencao Gangmu or “Index of Native Herbs”, which listed over 1,800 herbal remedies and their applications, to the Wubeizhi or “Treatise on Military Preparedness”, a comprehensive guide on weaponry, fortifications, and military strategies.

However, arguably the most influential Ming scholar was a man named Wang Yangming. Wang was a philosopher whose teachings were based on those of Zhu Xi, the founder of Neo-Confucianism, and his concept of the “extension of knowledge”. According to this concept, people should thoroughly investigate all things in order to garner knowledge. This included reading and classical studies on society and human relations, but also incorporated the study of nature and natural phenomena.

Wang, however, chose to go against the main principles of Zhu Xi’s philosophy by arguing that anyone could gain an understanding of universal concepts simply by carefully and rationally investigating things and events. In a bold move, he thus claimed that anyone, regardless of social standing or education, could become as wise as venerated masters like Confucius and Mencius. According to his theory, a peasant who had a great deal of experience and intelligence would therefore be wiser than an official who had memorised the Classics but had no practical experience of the real world.

Other officials frequently tried to diminish Wang’s influence by sending him off to deal with military affairs and rebellions far away from the capital, but he amassed a substantial following regardless and renewed the peoples’ interest in Taoism and Buddhism. Perhaps most significantly, he caused people to question the Confucian social hierarchy and debate whether certain professions, such as the scholar, should really rank above others, like the farmer.

Some of Wang Yangming’s disciples, such as the salt-mine worker Wang Gen and the scholar Li Zhi, would frequently give lectures that disseminated his philosophies. Wang Gen advocated that commoners pursue academics in order to better their everyday lives, while Li Zhi radically contended that women were the intellectual equals of men and should be offered the same education. Their “dangerous ideas” eventually landed them in prison, but it was not long before China’s civilians began embracing them.

While writers and philosophers were striking out in bold new directions, artists and artisans weren’t far behind. The Ming Dynasty has long been esteemed for the diversity and quality of its crafted wares, particularly with reference to cloisonné and porcelain. The most famous of these is the iconic blue-and-white porcelain, which was a hot commodity in Europe at the time. When it came to painting, the style of the time was greatly influenced by the Four Masters of the Wu School: Shen Zhou, Qiu Ying, Tang Yin, and Wen Zhengming. They were the most highly esteemed artists of their age, and their work prompted a movement away from the academic, instead placing emphasis on individualistic self-expression and technical excellence.

While writers and philosophers were striking out in bold new directions, artists and artisans weren’t far behind. The Ming Dynasty has long been esteemed for the diversity and quality of its crafted wares, particularly with reference to cloisonné and porcelain. The most famous of these is the iconic blue-and-white porcelain, which was a hot commodity in Europe at the time. When it came to painting, the style of the time was greatly influenced by the Four Masters of the Wu School: Shen Zhou, Qiu Ying, Tang Yin, and Wen Zhengming. They were the most highly esteemed artists of their age, and their work prompted a movement away from the academic, instead placing emphasis on individualistic self-expression and technical excellence.

Yet perhaps the greatest cultural influence on the Ming Dynasty came in the form of foreign traders. Foreign envoys were originally permitted to buy and sell private goods at official, supervised marketplaces, which were located both in the capital and in certain coastal cities. The Ming government was infamously strict when it came to foreign trade and eventually banned private trade between foreigners and native Chinese, even going so far as to close all of the maritime trading ports except Guangzhou during the 16th century. However, merchants weren’t about to let that stop them. After all, money is the great motivator!

In 1514, Portuguese traders began illegally smuggling goods in and out of China, much to the Ming court’s discontent. They were so persistent in their activities that by 1557 they had taken control of present-day Macau and were even trading regularly at Guangzhou. Once the Portuguese had found their way in, the Spanish and the Dutch soon followed suit. By 1637, even the English had begun illegally trading with China. Silk, porcelain, thoroughbred horses, and Chinese tea flowed out of the country, while silver and precious spices were brought in. However, the Ming imperials still regarded much of this activity as piracy, and it severely hampered their opinion of Europeans.

This made life particularly difficult for the Christian missionaries who had travelled from Europe to China. It was only when Matteo Ricci, a Jesuit who spoke fluent Chinese and was well-acquainted with Confucian principles, arrived in 1583 that the reputation of European foreigners began to change. By the time of his death in 1610, a handful of Chinese officials had converted to Christianity, and Jesuit communities could be found throughout central and southern China. In fact, he was held in such high regard that the Emperor even allowed his remains to be buried in Beijing and eventually other missionaries would be buried in the same spot, which came to be known as the Zhalan Cemetery. It was these Jesuits who produced a number of books in Chinese about European science and theology. Although their effect was quite limited, European technology and ideas were beginning to take hold in China towards the end of the Ming Dynasty.

This made life particularly difficult for the Christian missionaries who had travelled from Europe to China. It was only when Matteo Ricci, a Jesuit who spoke fluent Chinese and was well-acquainted with Confucian principles, arrived in 1583 that the reputation of European foreigners began to change. By the time of his death in 1610, a handful of Chinese officials had converted to Christianity, and Jesuit communities could be found throughout central and southern China. In fact, he was held in such high regard that the Emperor even allowed his remains to be buried in Beijing and eventually other missionaries would be buried in the same spot, which came to be known as the Zhalan Cemetery. It was these Jesuits who produced a number of books in Chinese about European science and theology. Although their effect was quite limited, European technology and ideas were beginning to take hold in China towards the end of the Ming Dynasty.