The Western Han Dynasty (206 BC-9 AD) and the Xin Dynasty (9-25 AD)

When Emperor Gaozu took power and established the Han Dynasty, he enfeoffed several of his relatives as princes and allowed them to rule over ten semi-autonomous kingdoms in the east. Talk about keeping it in the family! During his reign, tensions between the Han and Xiongnu people began to rise. Like Coca Cola versus Pepsi, this set the precedent for one of history’s greatest rivalries. He set a trade embargo against the group and even mounted surprise attacks on Xiongnu people while they traded at border markets. In retaliation, Xiongnu forces invaded modern-day Shanxi province and defeated Han troops. These skirmishes eventually led to the 44-year-long Han-Xiongnu War, which began in 133 BC and was one of the bloodiest in Chinese history. And you thought your neighbours were bad!

Although it happened as a consequence of his actions, it was a war that the first Han emperor would luckily be spared from seeing, as Emperor Gaozu died in 195 BC. He was succeeded by his son Emperor Hui, who indulged in so much hedonistic behaviour that he promptly passed away in 188 BC, aged just 22 years old. Sometimes the apple really does fall far from the tree! He was briefly succeeded by his two infant sons Liu Gong and Liu Hong before his half-brother, Liu Heng, finally took the throne as Emperor Wen.

Alongside his father Gaozu and his descendant Emperor Wu, Wen came to be regarded as one of the three greatest emperors of the Western Han Dynasty. He listened to the advice of his statesmen, yielded when it was necessary, and shunned the typical extravagance of previous emperors; in short, he was an ideal ruler according to Confucian principles. It was Emperor Wen who first introduced the concept of electing imperial officials based on examinations, which proved to be a model that lasted right up until the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912). Under his steady hand, China’s economy and political power flourished.

Alongside his father Gaozu and his descendant Emperor Wu, Wen came to be regarded as one of the three greatest emperors of the Western Han Dynasty. He listened to the advice of his statesmen, yielded when it was necessary, and shunned the typical extravagance of previous emperors; in short, he was an ideal ruler according to Confucian principles. It was Emperor Wen who first introduced the concept of electing imperial officials based on examinations, which proved to be a model that lasted right up until the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912). Under his steady hand, China’s economy and political power flourished.

Unfortunately it seemed his son, Emperor Jing, was far less concerned with keeping the peace and tragically brought about a period of unrest known as the Rebellion of the Seven States. What started out as a dispute between the Emperor and his cousin ended in a ferocious civil war that lasted for over three months. Now that’s one serious family feud! As a result of this atrocity, in 145 BC the princes were stripped of their privileges. Their territories were divided into commanderies, they were no longer allowed to appoint their own staff, and their personal income was made up of just a small portion of the tax they collected. In essence, they were just glorified taxmen!

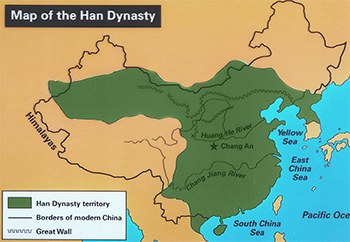

Yet it was Emperor Jing’s son, Liu Che, who would be singled out repeatedly by historians for special praise. He took the name Emperor Wu and not only boasted the longest reign of all the Han emperors, but was revered as a brave ruler who repeatedly extended the territory of the empire. To this end, he built long stretches of earthen wall along the northern frontier in order to protect his western territory from the northern Xiongnu people. This would eventually form the foundation of the Ming Dynasty Great Wall and relics of this original Han Dynasty wall, such as the Yumen Pass and the Yang Pass, can still be visited today. He was also famously fascinated with the Western Regions and even drove the Xiongnu out of modern-day Gansu province and Xinjiang in order to form friendly ties with the Western peoples. This was the key to his success as a ruler, as it allowed him to establish significant control over the Silk Road. On his death in 87 BC, he left behind a considerably larger empire than he had inherited.

Yet it was Emperor Jing’s son, Liu Che, who would be singled out repeatedly by historians for special praise. He took the name Emperor Wu and not only boasted the longest reign of all the Han emperors, but was revered as a brave ruler who repeatedly extended the territory of the empire. To this end, he built long stretches of earthen wall along the northern frontier in order to protect his western territory from the northern Xiongnu people. This would eventually form the foundation of the Ming Dynasty Great Wall and relics of this original Han Dynasty wall, such as the Yumen Pass and the Yang Pass, can still be visited today. He was also famously fascinated with the Western Regions and even drove the Xiongnu out of modern-day Gansu province and Xinjiang in order to form friendly ties with the Western peoples. This was the key to his success as a ruler, as it allowed him to establish significant control over the Silk Road. On his death in 87 BC, he left behind a considerably larger empire than he had inherited.

Unfortunately he was succeeded by his eight-year-old son, Emperor Zhao. While most of us were still trying to learn how to ride a bicycle, Zhao was busy learning how to run an entire country! His thirteen-year reign was marked by peace but, in an almost comical turn, his grandnephew and successor Liu He was made Emperor for just 37 days before being deposed by a powerful minister named Huo Guang. Imagine just how terrible you have to be at your job to get fired in less than 2 months! He was succeeded by Emperor Xuan, who had grown up as a commoner and thus understood the suffering of the people. The country prospered under his reign and many historians regard his death as the point when the Western Han Dynasty began to decline.

His son, Emperor Yuan, was notoriously indecisive and his inability to quash political squabbles meant that the state of the empire deteriorated. He was followed by Emperor Cheng, who was a womaniser and a drunk; Emperor Ai, who was equally as ineffectual; and Emperor Ping, who was just nine years old when he took the throne and fourteen when he died. It was this string of incompetent rulers that laid the foundation for Wang Mang’s eventual usurpation. Ping’s cousin Liu Ying was meant to take the throne but, on January 10th 9 AD, the Emperor Regent Wang Mang claimed it for himself and established the Xin Dynasty (9-23 AD).

Wang tried to appeal to the poorer classes by eliminating private landholding, introducing new currencies, and abolishing private slavery, but this antagonised the wealthy aristocracy and inevitably led to many noblemen defying him. After all, you should never bite the hand that feeds, nor the one that pays the most taxes! In the course of the ensuing warfare, the capital of Chang’an was almost completely destroyed. Meanwhile, massive floods from 3 to 11 AD caused the Yellow River to overflow. Farmers whose homes had been subsequently destroyed were forced to join roving bandit groups in order to survive. One such group, named the Red Eyebrows, became so large that they were able to defeat Wang Mang’s army, take control of the capital, force their way into the palace, and murder Wang in a most brutal fashion. Like Macbeth, it was Wang’s blind ambition that led to his inevitable downfall.

During the Warring States Period (c. 476-221 BC), China as we known it was separated into seven major warring kingdoms known as the Yan, Zhao, Qi, Chu, Han, Wei, and Qin. Each of these states vied for dominance, but for a long time they all appeared to be equally matched. Part of the reason for this was, believe it or not, because of their dedication to good manners! From the Spring and Autumn Period (c. 771-476 BC) onwards, the popular philosophy designated warfare as a gentleman’s activity, much like the concept of chivalry in Europe. It was considered improper to take advantage of an enemy’s weaknesses and there was a certain etiquette involved when it came to engaging in battle. Like a spot of English afternoon tea, it was of paramount importance to remain polite! Yet, during the 4th century BC, a Qin statesman named Lord Shang Yang emerged, and it was his philosophy of Legalism that would change the political and military landscape forever.

During the Warring States Period (c. 476-221 BC), China as we known it was separated into seven major warring kingdoms known as the Yan, Zhao, Qi, Chu, Han, Wei, and Qin. Each of these states vied for dominance, but for a long time they all appeared to be equally matched. Part of the reason for this was, believe it or not, because of their dedication to good manners! From the Spring and Autumn Period (c. 771-476 BC) onwards, the popular philosophy designated warfare as a gentleman’s activity, much like the concept of chivalry in Europe. It was considered improper to take advantage of an enemy’s weaknesses and there was a certain etiquette involved when it came to engaging in battle. Like a spot of English afternoon tea, it was of paramount importance to remain polite! Yet, during the 4th century BC, a Qin statesman named Lord Shang Yang emerged, and it was his philosophy of Legalism that would change the political and military landscape forever.

In order to rule such a vast territory, the Qin court opted for a strict, totalitarian regime. They began by abolishing feudal privileges and standardising everything, from weights and measurements to currency and the writing system. After all, you can’t get jealous of someone when they have the exact same things as you! This was perhaps one of their most revolutionary and influential reforms, as Li Si’s creation of a uniform writing system helped greatly in uniting the country. Yet Qin Shi Huang wasn’t content with just controlling his citizens’ material lives; he also sought to dominate them mentally.

In order to rule such a vast territory, the Qin court opted for a strict, totalitarian regime. They began by abolishing feudal privileges and standardising everything, from weights and measurements to currency and the writing system. After all, you can’t get jealous of someone when they have the exact same things as you! This was perhaps one of their most revolutionary and influential reforms, as Li Si’s creation of a uniform writing system helped greatly in uniting the country. Yet Qin Shi Huang wasn’t content with just controlling his citizens’ material lives; he also sought to dominate them mentally.