The sprawling city of Jingdezhen is perhaps better known throughout the world as the “Porcelain Capital” of China. For over 1,000 years, it has been renowned as the production centre for the finest quality Chinese ceramics in the country and its well-documented history of porcelain artisanship stretches back for more than 2,000 years. Although Jingdezhen did not become a major manufacturer of imperial porcelain until the Song Dynasty (960-1279), historical documents indicate that it was producing pottery as early as the Han Dynasty (206 BC–220 AD), when it was a market town known as Xinping. Situated along the banks of the shimmering Chang River, it was renamed to Changnan or “South of the Chang” during the Tang Dynasty (618-907).

In fact, it wasn’t given the illustrious name Jingdezhen until 1004, which represented a major turning point in the town’s history. “Jingdezhen” literally translates to mean “Town of Jingde” and refers to the reign of Emperor Zhenzong, which was known as the Jingde era. It was honoured with this name because it was during the Jingde era that Jingdezhen truly became famous throughout China for its porcelain wares. In fact, even though Jingdezhen was upgraded to the status of “city” after 1949, it still retains its original name in homage to its heritage.

The sudden boom in the quality and production of porcelain is typically attributed to the advent of the Jin invasion, as talented ceramic workers from the north were forced south due to warfare and took refuge in Jingdezhen. When the imperial capital was finally moved south to Lin’an (modern-day Hangzhou) after the Jin Dynasty (1115-1234) annexed northern China, Jingdezhen’s reputation as a major trading and production hub for ceramics was solidified.

It was during the Song period that Jingdezhen became particularly famous for a type of porcelain known as Qingbai (青白) or “Blueish-white” ware. This is not to be confused with the later blue-and-white style of porcelain, as Qingbai ware is not bicolour and is instead characterised by its solid white colour with a blueish tint. This style of porcelain was simply decorated by delicately carving or incising patterns into the surface, rather than painting patterns onto the porcelain. Arguably one of the most famous pieces of Qingbai porcelain is known as the Fonthill Vase, which was crafted in Jingdezhen during the 14th century and is the earliest documented piece of Chinese porcelain to have reached Europe.

While the traditional blue-and-white porcelain that Jingdezhen has become famous for reached its peak production during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), the trend was actually started and rose to popularity during the Yuan Dynasty! This is simply because the Mongolian people, who controlled China at the time, were enamored with this colour scheme, as the colours of blue and white carried deep significance in Mongolian culture.

A collection of British Museum

It was during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), however, that Jingdezhen reached its apotheosis as the official centre for imperial porcelain production and large quantities of blue-and-white porcelain were manufactured. It was during this dynasty that official imperial kilns were established at Pearl Hill in Jingdezhen. By 1402, Jingdezhen was home to twelve imperial kilns and was one of only three areas in the country that had been granted this privilege. Although these kilns were controlled by and limited exclusively to the Emperor, the imperial court generated a surprisingly large demand for porcelain.

Alongside the main palaces and imperial residences, there were the regional courts of princes, imperial temples, monasteries, and shrines that all needed to be supplied with well-crafted porcelain on a reasonably regular basis. On top of this, the Emperor also required a substantial supply of porcelain to give as gifts. For example, in 1433, the palace placed a single order for 443,500 pieces of porcelain! In order to meet this demand, the imperial kilns hired hundreds of workers, whose duties were separated depending on their specialty.

According to regulations dating back to 1899, the Emperor was entitled to 1,014 pieces of yellow porcelain per year and his mother the Empress Dowager Cixi was permitted 821. By contrast, a concubine of the first rank was given 121 pieces of yellow porcelain with a white interior, while concubines of the second rank had to settle for yellow porcelain that had been decorated with green dragons. These porcelain wares were not simply for decoration; the amount and style of the porcelain also served to demonstrate the imperial rank of their owner. Since yellow was the colour of the imperial household, the amount of pure yellow in a piece of porcelain indicated how high the owner’s status was.

Tragically, the fall of the Ming Dynasty and the rebellion of Wu Sangui in 1675 heralded destruction for Jingdezhen. Immediately thereafter, however, the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912) took great pains to rebuild the town and founded a government ceramics factory in place of the previous imperial kilns. Thanks to the work of three accomplished directors, known as Zang Yingxuan, Nian Xiyao, and Tang Ying, ceramics production in Jingdezhen once again rose to the finest quality. Porcelain produced during this time was also marked by its adventurous nature, as ceramicists had unprecedented freedom and access to resources that allowed them to use new patterns and styles.

It was during the Qing Dynasty that famille-style porcelain rose to popularity, which was characterised by its use of various colour “families” and was named after the dominant colour. For example, famille rose porcelain utilised various shades of pink and famille verte porcelain focused largely on the colour green. The copying of famous porcelain wares from previous dynasties was also popularised during the Qing Dynasty. All 9,000 original kilns in Jingdezhen were tragically destroyed during the Taiping Rebellion (1850-1864) and weren’t rebuilt until after 1866. The town’s popularity, however, rarely waned, and it even served as the main producer of porcelain badges and statues of Mao Zedong during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976).

To this day, Jingdezhen remains one of the major producers of porcelain in China and antique porcelain from Jingdezhen is prized by collectors throughout the world. The highest price ever achieved for a piece of porcelain was for a blue-and-white porcelain jar produced in Jingdezhen during the Yuan Dynasty, which sold in 2005 for a whopping 230 million yuan (over 25 million pounds or 32 million dollars). To put that into perspective, that’s enough money to buy roughly 100 Ferrari sports’ cars!

In spite of its remote and mountainous location, one of the main reasons why Jingdezhen flourished as a centre for porcelain production was due to its proximity to high quality deposits of kaolin or china clay, petuntse or porcelain stone, coal, manganese, and lime. It was surrounded by pine forests, which provided wood for the kilns, and it was located close to a river, meaning that its fragile wares could be easily transported throughout the country by boat. Alongside the domestic market, there was huge demand for porcelain to be exported from Jingdezhen to Japan, all of Southeast Asia, and much of the Middle East. In fact, the large round serving-plates that were produced in Jingdezhen were exclusively for the Middle Eastern market, as Chinese people would traditionally use bowls instead of plates.

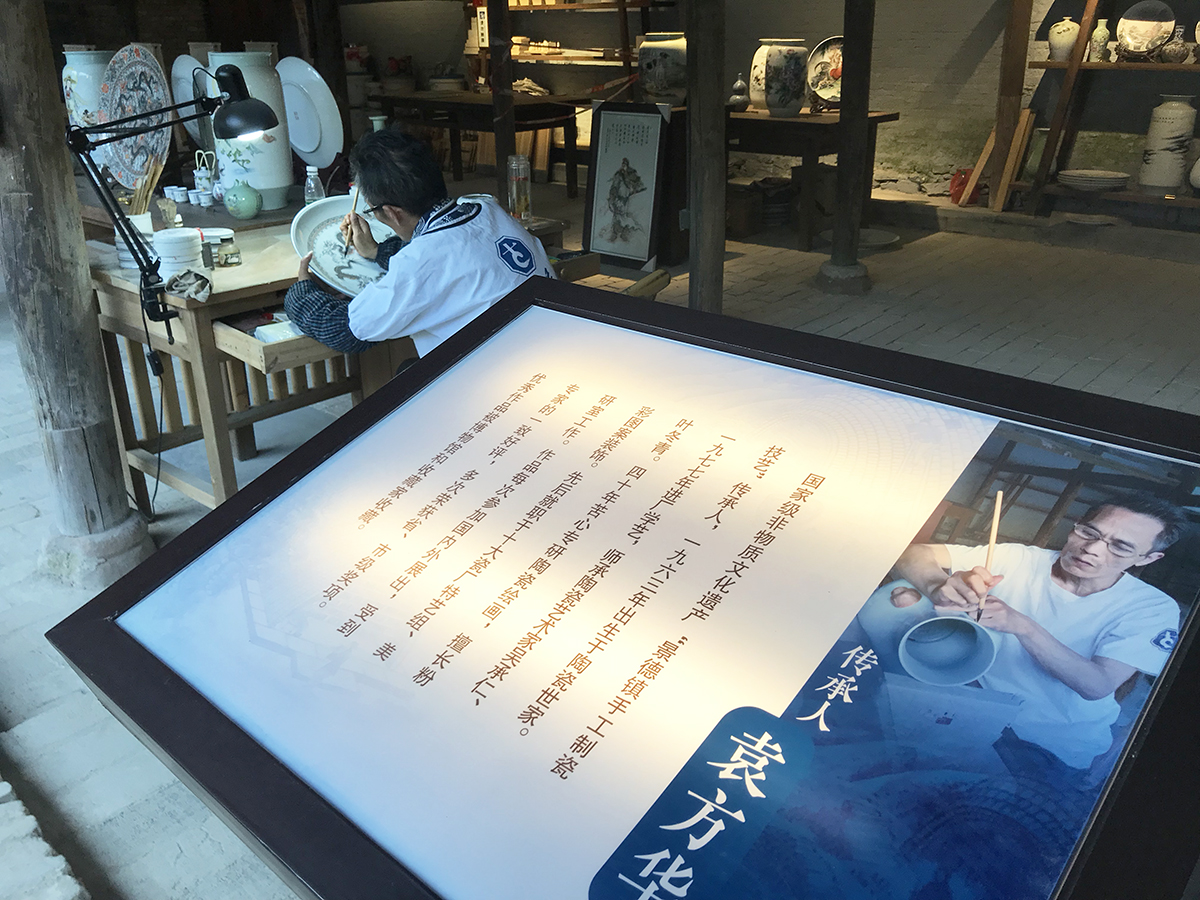

Nowadays, the ideal place to connect with Jingdezhen’s venerable legacy of porcelain production is at the Jingdezhen Ceramics Museum and the Jingdezhen Ceramics Folk Museum. Just try not to get the two confused! The Jingdezhen Ceramics Museum is the first museum in the world to be dedicated solely to exhibitions about ceramics. It is currently separated into two sections: one section hosting modern ceramics; and one section exhibiting ancient ceramics. By contrast, the Jingdezhen Ceramics Folk Museum is actually a sprawling complex made up of several workshops, where visitors can witness first-hand how ceramics are moulded, fired, and painted in Jingdezhen following traditional methods.

Alongside the museums, Jingdezhen is also home to a wide variety of specialist markets, where visitors can browse the work of local ceramicists and even purchase some for themselves. Among the multifarious markets in Jingdezhen, the four most famous are Tao Yi Street, the Tao Xi Chuan Market, the Ming Qing Yuan Market, and the Ghost Market. Tao Yi Street is unsurprisingly a street where established artists from the area own their own shops and art studios. It is home to some of the most beautiful ceramics boutiques in Jingdezhen and the works sold along this street are of the finest quality, which naturally also makes it the most expensive place to buy ceramics!

By contrast, the Tao Xi Chuan Market is an open air flea market designed to provide exposure for young ceramists. The market is strictly organized by both the local government and a local culture management company, who work in tandem to help art students and local artists sell their works. All ceramists who want to exhibit their works at the market have to first go through an intense vetting procedure, where they submit a portfolio online. The market organizer selects only the most impressive portfolios and offers these ceramists the opportunity to sell their wares at Tao Xi Chuan. Like Tao Xi Chuan, the Ming Qing Yuan market is a flea market that is designed to help local artists exhibit their wares. However, the vetting procedure for Ming Qing Yuan is not as strict as that of Tao Xi Chuan, so you may find that the products won’t be of as high a standard.

Unlike the aforementioned markets, the Ghost Market is a very traditional type of market that isn’t strictly dedicated to ceramics and instead offers an abundance of different antiques. It is the oldest market in Jingdezhen and was originally started so that people could trade antiques back when it was illegal to do so during the early years of Communist rule. This is why the market was and continues to be held in the early hours of Monday morning, under cover of darkness! This market offers a variety of relics, including Communist paraphernalia, old coins, and jade ornaments. However, you must be particularly careful when shopping there, as there are numerous fake antiques that are mixed up with the authentic ones, and it is remarkably difficult to tell them apart. After all, you wouldn’t want to end up feeling haunted by a bad purchase!

Make your dream trip to Jingdezhen come true on our travel: Explore Traditional Culture in Picturesque Ancient Villages