At the beginning of the 18th century, Tibet was in turmoil as two powerful political groups became embroiled in the search for the next Dalai Lama. One group was led by a man named Lha-bzang Khan, who was the ruler of the Khoshut Khanate [1]. The leader of the opposing faction was known as Desi Sangye Gyatso and was widely regarded as the most powerful man in Tibet, particularly since he had been the regent of the 5th Dalai Lama. ON top of all of this internal political power, Desi Sangye Gyatso also had a good relationship with the Dzungar Khanate [2]. The conflict only ended because Desi Sangye Gyatso was murdered. It seems Lha-bzang Khan would not escape so lightly either, as the Dzungar Khanate invaded Tibet in 1717 and he was killed in the ensuing chaos.

The invasion subsequently quashed by an expedition sent by the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912 AD), which was the ruling regime of China at the time. This Qing military expedition expelled the Dzungars from Tibet in 1720. In 1721, they enthroned Kelzang Gyatso as the seventh Dalai Lama in a ceremony at the Potala Palace.

In spite of this outward calm, however, secret dissent and popular discontent was increasing during the new Tibetan cabinet era. This eventually led to the assassination of the leader and chaos reigned once again. The new ruling leader, a man named Polhané Sönam Topgyé, decided to take revenge on those who were responsible for the assassination. In a shocking twist, it was believed that the father of the seventh Dalai Lama had been involved in planning the assassination!

From here onwards, the story seems to diverge, as there are two different versions of what may have happened next. The seventh Dalai Lama was either summoned to Beijing by the Qing government but was stopped in Litang by Polhané Sönam Topgyé, or he was ordered to go to Litang, which was his birth place.

Regardless of the reasoning behind it, the seventh Dalai Lama Kelzang Gyatso was sent to Litang, where the Huiyuan Monastery was built for him. Meanwhile, the 5th Panchen Lama was called to Lhasa by the Qing emperor Yongzheng in order to take control of certain areas within the ancient region of Tibet. From then on, the Panchen Lama’s power was used to balance out the power of the Dalai Lama.

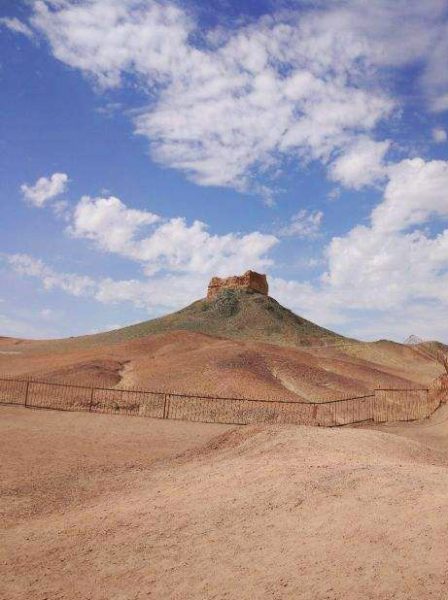

When you are standing in front of the Huiyuan Monastery, you may be surprised to find that such an isolated monastery with such a simple appearance is related to some of the most influential moments in Tibetan history. The Huiyuan Monastery belongs to the Gelug sect of Tibetan Buddhism and, in terms of its architecture, it follows the typical Tibetan Buddhist monastery style. You may get the feeling that the Huiyuan Monastery is a simplified version of the Drepung Monastery, but it incorporates some royal architectural features.

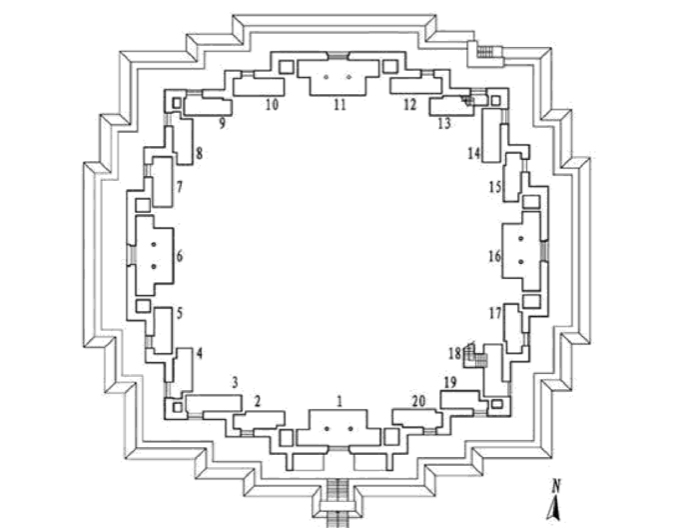

The monastery is located in the county of Daofu within the Garzê Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture. The entire complex covers a colossal area of around 83 acres and contains more than one thousand rooms. According to a typical monastery’s layout, the main structures are the Buddha Hall, the studying area for the monks, and the monks’ dormitories. Alongside these main structures, the Huiyuan monastery has something extra special, the steles pavilion, which is home to five steles that date back to the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911).

The 7th Dalai Lama Kelzang Gyatso lived within the Huiyuan Monastery for seven years. In 1735, the Yongzheng Emperor sent his own brother, Prince Guo, to help Kelzang Gyatso return to Lhasa. During his time at the monastery, Prince Guo wrote a long poem that described the local life and culture, which was made into a stele. However, it was destroyed during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976).

The significance of the Huiyuan Monastery didn’t end up when Kelzang Gyatso left. Over one hundred years later, fate would shine on the monastery yet again, as the 11th Dalai Lama Khedrup Gyatso was born near the Huiyuan Monastery. In response to this fortuitous event, the Qing court bestowed an honour known as the “Nine Dragons and Nine Lions” on the monastery. “Nine Dragons” refers to the Qing court, while “Nine Lions” represents the Kashag [3]of Tibet. Visitors can find the “Nine Dragons and Nine Lions” on the wall outside of the main hall.

During its long and venerable history, the Huiyuan Monastery was supported directly by the royal family of the Qing Dynasty. The buildings and Buddhist art in the monastery, however, were tragically damaged during the Cultural Revolution. In 1982, the government provided grants to the complex so that they could be repaired.

Every year, from the 1st to the 7th of June according to the Tibetan Calendar, a prayer ceremony and other religious activities are held in the Huiyuan Temple. Collectively, these festivities are known as the Mask Dance Festival.

On the first day, the monks who inhabit the temple will dance in gorgeously decorative dress, but without their iconic masks. The next day is dedicated entirely to the prayer ceremony, where worshippers pray for blessings and a brighter future. On the third day, the local people and monks will burn incense and make sacrifices to the gods in the hopes that their homes will be protected from future disasters. On the fourth day, the monks don their traditional dress again, along with their iconic masks, and perform the mask dance, which is known as the Cham Dance. From the 5th through to the final 7th day, there are horse racing events and other folk activities.

1) The Khoshut Khanate was a kingdom located on Tibetan Plateau, which ruled the area from 1642 to 1717.

2) The Dzungar Khanate (1634-1755) was an Inner Asian khanate ruled by the Oirat Mongolians.

3) The Kashag was the governing council of Tibet from 1721 right through until the 1950s.

Make your dream trip to the Huiyuan Monastery come true on our travel:

Explore the Mystery of Tibetan Culture Festival by Festival