During the early Han Dynasty (206 BC–220 AD), the western border of the empire was ceaselessly invaded and terrorised by the fearsome Xiongnu people. These hardy nomads were both feared and despised by the Han Chinese, who regarded them as their arch nemeses. Rather than meet the formidable Xiongnu warriors in battle, many of the Han rulers chose to marry off their daughters to Xiongnu leaders in a feeble attempt to broker peace. Yet it seemed that even the most beautiful maidens weren’t enough to quell the Xiongnu people’s desire for the fertile land that lay within Emperor’s territory! This was all set to change in 141 BC, when the valiant Emperor Wu rose to power.

He abolished this cowardly policy and replaced it with his own strategic military agenda. In 121 BC, fierce counterattacks led by the celebrated military general Huo Qubing eventually drove the Xiongnu troops out of the west and allowed Emperor Wu to secure the western frontier. In order to cement this victory, the Emperor established two vital fortifications: Yumen Pass and Yang Pass. By strengthening the border and helping to prevent further invasions from the Xiongnu, they became the most significant passes along the western section of the Great Wall. Located within the narrow Hexi Corridor, approximately 70 kilometres (43 mi) from Dunhuang, Yang Pass was once a military fortress beyond compare.

During the Tang Dynasty (618-907), it welcomed the return of the illustrious monk Xuanzang, whose fabled pilgrimage to the west was eventually immortalised in the Chinese classic Journey to the West by Wu Cheng’en. The name “Yang” literally translates to mean “Sun”, but is actually in reference to its location south of Yumen Pass. This is derived from the fact that, due to the geography of the region, the sun shone in the south for most of the day, so the word “sun” became synonymous with the word “south”. However, in spite of its fortuitous past and cheerful name, it seems that Yang Pass suffered from a much maligned reputation.

Both Yumen Pass and Yang Pass served as major trading posts along the Silk Road and acted as gateways to the mysterious Western Regions. Yang Pass swiftly became associated with the grief of parting, as it was often the place where people would see their loved ones off before they left the country on long journeys. In fact, the image of Yang Pass as a place of sorrow became so ingrained in Chinese culture that it featured frequently in Chinese literature, most notably in the Tang Dynasty poet Wang Wei’s “Seeing Yuan’er Off on a Mission to Anxi”. In the final line, Wang beseeches Yuan’er by saying: “Oh, my dear friend, let’s have one more cup of wine; out west beyond Yang Pass, old friends there’ll be none”.

This poem went on to inspire the “Three Variations of Yang Pass”, a classical farewell song from the Tang Dynasty that has become one of the most famous pieces of Chinese music. The term “three variations” refers to the fact that the song must be sung three times, either partially or wholly, with some changes added each time. The earliest surviving version dates back to the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), although the most popular is based on a score developed during the late Qing Dynasty (1644-1912). It seems oddly fitting that, like a noble swan song, this tragic melody would rise to popularity around the same time that Yang Pass fell into obscurity.

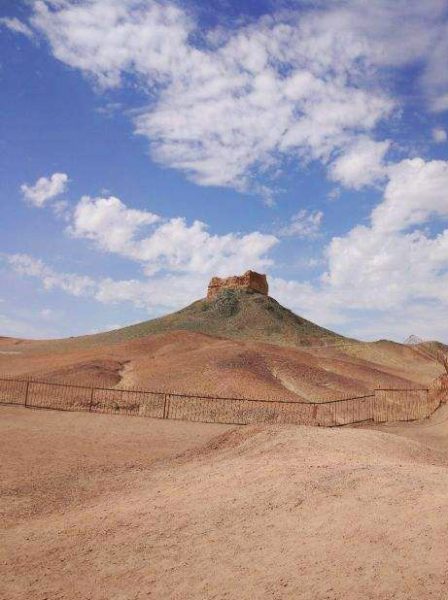

The decline of the Silk Road during the Song (960-1279) and Ming dynasties meant that Yang Pass gradually became obsolete and was eventually abandoned completely. It once was linked to Yumen Pass by a 64-kilometre (40 mi) stretch of wall, interspersed every 5 kilometres (3 mi) by a grand beacon tower. Nowadays, most of Yang Pass is buried under the shifting sands of the unforgiving desert. All that remains is a small section of wall and a single beacon tower measuring just 5 metres (16 ft.) in height. In 2003, the Yang Pass Museum was opened and features nearly 4,000 ancient Han Dynasty artefacts, paintings, and exhibitions about the history of this venerable gateway. It was built to imitate what the pass would have looked like in its heyday, complete with its own gate tower, general’s office, and barracks. In fact, it’s so well-designed that it could almost pass for the real thing!