The name “Longjing” literally means “Dragon Well” and is unsurprisingly named after the Dragon Well in Longjing Village, which rests just outside of Hangzhou in Zhejiang province. According to legend, this well was used as a tunnel by a local dragon to move freely between the lakes of Hangzhou and the East China Sea. Nowadays Longjing is heralded as one of the finest teas in China and is renowned for its “four wonders”: its emerald green colour, its strong and sumptuous aroma, its subtly sweet flavour, and the pleasing appearance of its delicate, flat leaves. The best quality Longjing comes from the West Lake area, although to be classified as “authentic” it need only come from Zhejiang province.

The tradition of growing Longjing dates back over 1,200 years, but it wasn’t popularised until the Song Dynasty (960-1279). During the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912), it was granted the status of “Gong Cha” or imperial tea by the Kangxi Emperor, meaning it was an acceptable type of tea to be given as tribute to the imperial court. One legend states that the Kangxi Emperor’s grandson, the Qianlong Emperor, was visiting Hu Gong Temple near West Lake when he was presented with a cup of Longjing tea. He was so impressed that he conferred imperial status upon the 18 tea bushes that grew near the temple. These bushes are still alive today and the tea they produce commands a higher price per gram than the equivalent weight in gold!

Another legend states that, on a similar such visit, the Qianlong Emperor was watching some ladies pick the tea and became enamoured by the effortlessness and dexterity of their movements. He decided to try picking the tea for himself, but he’d not long started when he received a message saying that his mother, the Empress Dowager Chongqing, was ill. Without thinking, he shoved the tea leaves into his sleeves and immediately began his return journey to Beijing. When he arrived at the imperial palace, he went to visit his mother and she quickly noticed the enticing aroma of the tea. He brewed it for her and she praised it for its fine taste, claiming that its health benefits helped her overcome her illness. Nowadays the characteristic flattened shape of the leaves is meant to mimic the appearance of those that travelled in the Qianlong Emperor’s sleeves.

In order to make Longjing tea, first the leaves are carefully hand-picked and then left to wither, either in a warm room or outside, for between 6 to 12 hours. This is to reduce some of the moisture content but, unlike black and oolong teas, it should not be allowed to go through the natural oxidation process. The tea is then separated and roasted based on its quality, as high grade tea should be roasted at a different temperature to low grade tea. The leaves are pan-fried in a large, red-hot wok for about 15 minutes before being allowed to cool.

This is perhaps the most significant and difficult part of the process, as it is all done by hand and requires the skill of a master tea roaster. They shift and press the leaves against the wok with their bare hands, so that they can feel the gradual change of the leaves. We’re sure you’ll agree that being a tea roaster is not everyone’s cup of tea! After the leaves have been allowed to cool, they are fried a second time to perfect their flat, spear-like shape. If the tea roaster puts too much pressure on them then they will become too dark in colour, but not enough pressure and they will be the wrong shape. Let’s just say there’s a lot of pressure on the tea roaster to get it right!

In terms of quality, it can be separated into six grades: superior, and then 1 to 5. How highly a tea is graded depends on where it is from and when it was picked. The best quality Longjing tea is picked right before the Qingming Festival, which takes place on the 15th day after the Spring Equinox (usually April 4th or 5th), and is thus referred to as Mingqian or “Pre-Qingming” Longjing. Any tea picked before the Grain Rain Season, beginning from April 19th to 21st each year, is still considered good quality and is called Yuqian or “Pre-Rain” Longjing, but tea picked after this season is widely regarded as worthless.

Xihu or “West Lake” Longjing is perhaps the most famous variety and is grown in a designated area of just 168 square kilometres (65 sq. mi). Originally it was separated into four sub-regions: Lion (Shi), Dragon (Long), Cloud (Yun), and Tiger (Hu). Nowadays there is less distinction between the teas from these sub-regions, so any tea from the West Lake region that is not from Lion Peak or Meijiawu Village is referred to as Xihu Longjing. Tea that is picked from the bushes grown on Shi Feng or “Lion Peak” is called Shi Feng Longjing and supposedly has a fresh taste, a sharp, long-lasting fragrance, and a far more yellowish colour than other varieties of Longjing.

Meijiawu Longjing comes exclusively from Meijiawu Village and is renowned for its deeply jade green colour. Qiantang Longjing refers to any type of Longjing tea that comes from outside of the Xihu district and is generally regarded as inferior in quality, meaning it is markedly cheaper. On top of these four broad designations, there are potentially as many varieties of Longjing as there are tea leaves in a cup!

Bear in mind, high quality Longjing can be very expensive so, if you do decide to indulge, be sure to prepare it properly! Ideally it should be infused with water that has been heated to between 75°C and 80°C (167-176°F) and should be left to steep for approximately 3 to 4 minutes, until the water has turned a slight yellowy green colour. High quality tea will produce this yellowish colour, while low quality tea tends to be more bluish or deep green in hue. Local legend states that the best Longjing is made using water from the Running Tiger Spring just outside of Hangzhou, as the water is deliciously pure and enhances the subtle flavours of the tea perfectly.

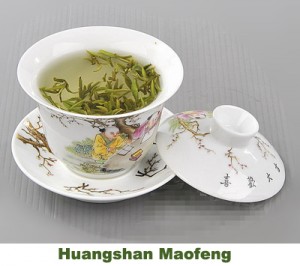

At 700 to 800 metres above sea level, the area around and on Huangshan Mountain, is the perfect place and main area of production for the superfine Huangshan Maofeng tea leaves. Huangshan Maofeng is produced in several different places on the mountain, including Peach Blossom Peak, Purple Cloud Peak, Cloud Valley Monastery, Pine Valley Temple and Hanging Bridge Temple. In fact, Huangshan Maofeng is produced throughout the whole Huizhou District. This region boasts a temperate climate and receives plenty of rainfall. The annual average temperature is between 15 to 16°C, and the average amount of precipitation is between 1,800 to 2,000 millimetres. The soil is deeply layered and made up of the yellow earth typically found in mountainous regions. This type of soil is loose in texture and has good water permeability. It contains an abundance of organic matter and phosphorus potassium, and it has an acidity level of between ph 4.5 and 5.5 which makes it suitable for the growth of tea trees.

At 700 to 800 metres above sea level, the area around and on Huangshan Mountain, is the perfect place and main area of production for the superfine Huangshan Maofeng tea leaves. Huangshan Maofeng is produced in several different places on the mountain, including Peach Blossom Peak, Purple Cloud Peak, Cloud Valley Monastery, Pine Valley Temple and Hanging Bridge Temple. In fact, Huangshan Maofeng is produced throughout the whole Huizhou District. This region boasts a temperate climate and receives plenty of rainfall. The annual average temperature is between 15 to 16°C, and the average amount of precipitation is between 1,800 to 2,000 millimetres. The soil is deeply layered and made up of the yellow earth typically found in mountainous regions. This type of soil is loose in texture and has good water permeability. It contains an abundance of organic matter and phosphorus potassium, and it has an acidity level of between ph 4.5 and 5.5 which makes it suitable for the growth of tea trees.