Towards the end of the Tang Dynasty (618-907), military governors known as jiedushi began to accrue power outside of imperial rule. They controlled expansive regions and commanded large armies, making them very difficult for the imperial government to control. After the brutal Huang Chao Rebellion (874-884), the Tang Empire was virtually crippled and the jiedushi effectively became rulers of their respective territories. When one such jiedushi, named Zhu Wen, finally overthrew the Tang Dynasty in 907, China had already been divided up among a series of rival regimes. While five consecutive dynasties ruled over the north, the south and the west were fractured into a series of kingdoms that regularly ran concurrently.

Although a number of small kingdoms formed during this time, traditionally only ten major ones are listed. These were known as the Wu (902–937), the Southern Tang (937–976), the Jingnan (924–963), the Min (909–945), the Chu (927–951), the Former Shu (907–925), the Later Shu (934–965), the Northern Han (951–979), the Southern Han (917–971), and the Wuyue (907–978).

The Kingdom of Wu

The Kingdom of Wu controlled a south-central region known as Huainan, which included modern-day central and southern Anhui province, central and southern Jiangsu province, much of Jiangxi province, and eastern Hubei province. It was founded by a man named Yang Xingmi, who had been a volunteer soldier during the Tang Dynasty. Through cunning military strategies, he was eventually named Prince of Wu by the Tang court, although it wasn’t until his son Yang Wo took over that Wu was declared an independent sovereign state.

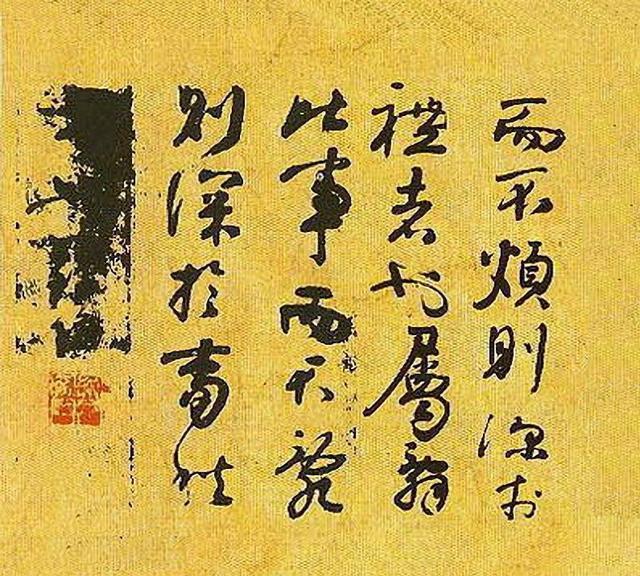

Having ascended the throne at a very young age, Yang Wo relied on an official named Xu Wen, whose power he gradually came to resent. His suspicions turned out to be well-founded, as Wen and a colleague assassinated Wo in 908. After a falling out between the crafty pair eventually resulted in the colleague’s untimely death, Wen installed Yang Wo’s brother, Yang Longyan, as a puppet ruler. Wen was succeeded by his step-son, Xu Zhigao, on his death in 927, and this represented a turning point for the Wu regime. Zhigao deposed the reigning Yang Pu and adopted the surname “Li”, which had been that of the Tang royal family. To this end, he proclaimed the restoration of the Tang Dynasty and established the Kingdom of Southern Tang.

The Kingdom of Southern Tang

By comparison to the other Ten Kingdoms, the Southern Tang would prove to be relatively stable and prosperous. When Li Bian’s son, Li Jing, took over in 943, he embarked on a campaign that would greatly expand his empire. In particular, his military intellect allowed him to take advantage of a revolt in the Kingdom of Min. When the Min appealed to the Southern Tang for help, Li Jing instead absorbed the rebellious territory into his own. It seemed that the Min had trusted the Southern Tang an inch and suddenly they were out by miles, of territory that is! By 945, the Southern Tang had completed its conquest of the Min and annexed all of its lands.

In a similar way, the Southern Tang was able to exploit internal strife within the Kingdom of Chu and eventually conquered it in 951, expanding their empire even further. However, tragedy struck when the Song Dynasty was founded in the north of China. After almost a year of fighting, the Southern Tang was defeated by the Song in 975 and their empire was formally seized in 976.

The Kingdom of Jingnan

That being said, the Southern Tang wasn’t the first to go. The Kingdom of Jingnan, which only covered two small districts on the Yangtze River and was the smallest of the southern kingdoms, suffered much the same fate. It was initially founded by a military governor named Gao Jichang, who had served under the Later Liang Dynasty (907–923) but declared independence when they were conquered by the Later Tang (923–36).

As a small and rather weak state, Jingnan was incredibly vulnerable to its powerful neighbours. It survived largely by maintaining crucial alliances with the dynasties that ruled northern China and its status as a central trading hub also helped to protect it from invasion. However, when the Song Dynasty’s armies invaded Jingnan territory in 963, they had neither the manpower nor the finances to defend themselves, and so promptly surrendered.

The Kingdom of Min

The Kingdoms of Min and Chu would not be so lucky, as they would find themselves brutally conquered long before the Song Dynasty was established. The Kingdom of Min, which was established in 909 by a military governor named Wang Shenzhi, covered a mountainous region in modern-day Fujian province and held its capital at Changle (modern-day Fuzhou). The territory it occupied was isolated and rugged, meaning it was one of the least economically prosperous of the Ten Kingdoms. However, they were also in an advantageous position to engage in maritime trade and this set the stage for Fujian province to become a vital trading port during future dynasties.

Tragedy struck in 943, when Wang Shenzhi faced a rebellion from one of his own sons, who took control of the kingdom’s northwestern territory and established the Kingdom of Yin. The Min court begged assistance from the nearby Kingdom of Southern Tang but, rather than helping them, the Southern Tang simply invaded the Kingdom of Yin and annexed its territory! Not long thereafter, the Kingdom of Min was absorbed entirely into the Southern Tang.

The Kingdom of Chu

The Kingdom of Chu was a close neighbour to the Min, controlling modern-day Hunan province and northeastern Guangxi. It was founded by a military governor named Ma Yin and, under his rule, Chu was a peaceful and prosperous state that became known for exporting horses, silk, and tea. However, Ma Yin’s death led to conflicts within the royal family that eventually proved to be the downfall of the kingdom. The Southern Tang, fresh from its conquest of the Min, immediately took advantage of this crisis and seized the kingdom in 951.

The Kingdoms of Former and Later Shu

Meanwhile, other kingdoms in western China were experiencing mixed luck. The Kingdom of Former Shu, which ruled over modern-day Sichuan province, southern Gansu province, and southern Shaanxi province, was established by a military governor named Wang Jian. When he passed away in 918, he was succeeded by his incompetent son, Wang Yan. In its weakened state, the kingdom was invaded by the Later Tang Dynasty and its territories were swiftly occupied.

However, unbeknownst to the Later Tang imperial court, one of their military governors was amassing power. His name was Meng Zhixiang and, in 930, he entered into open rebellion. Although the rebellion was successful, Meng decided to remain a vassal of the Later Tang until it was obvious that the dynasty was in decline. He finally declared independence in 934 under the Kingdom of Later Shu, but died less than a year later. His son, Meng Chang, ruled effectively for thirty years until the Later Shu was conquered by the Song Dynasty in 965.

The Kingdoms of Southern and Northern Han

Unlike the Former Shu and the Later Shu, which were named because they reigned over the region known as Shu, the Southern Han and the Northern Han were so-called because their rulers claimed descent from the royal Liu family of the venerable Han Dynasty (206 BC–220 AD). The Kingdom of Southern Han held its capital in Guangzhou and controlled parts of modern-day Guangdong province, Guangxi, the island of Hainan, and Hanoi in Vietnam. It was established by a military officer named Liu Yin, although it didn’t officially claim independence until after Liu Yin’s death in 917, when his brother Liu Yan took the throne. It maintained steady leadership for over 60 years, until it was finally forced to submit to the Song Dynasty in 971.

It was the Kingdom of Northern Han that would truly prove to be the thorn in the Song Dynasty’s side. When the short-lived Later Han Dynasty (947–951) fell, the royal family fled back to their stronghold in Shanxi province and established the Northern Han in its stead. Its ruler, Liu Min, immediately restored the relationship that his family had once held with the mighty Khitan people, who founded the Liao Dynasty (916–1125). It was this alliance that would prove to be the Northern Han’s saving grace as, in spite of their small size, they were protected by an ally whose power equalled that of the Song Dynasty.

It was only after the Song Dynasty had annexed all of the other rival kingdoms that it finally turned its attention to the Northern Han. In the end, Song forces laid siege to its capital of Taiyuan and, after two long months, it finally surrendered. However, though the Northern Han may have been the last of the Ten Kingdoms to fall, it was by no means the most influential.

The Kingdom of Wuyue

The Kingdom of Wuyue, which survived throughout the entirety of the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms Period, was arguably the most significant regime of this turbulent era. It covered modern-day Zhejiang province and Shanghai Municipality, as well as the southern portion of Jiangsu province, and was founded by the Qian family. The name Wuyue was derived from a combination of Wu and Yue, which were ancient kingdoms that had ruled during the Spring and Autumn Period (c. 771-476 BC). However, while the Wuyue’s territory roughly covered that of the ancient Yue, it included very little of ancient Wu. This led to accusations by the Kingdom of Wu that the Wuyue had designs on their territory and the name became a source of tension between them. In short, it was a real case of naming and shaming!

Under its first king, Qian Liu, the Wuyue thrived economically and rapidly developed its own regional culture, one that survives to this day. This set a precedent for his descendants, which would be strictly followed by four succeeding kings. The kingdom’s coastal location meant that it was able to establish diplomatic relations with several other countries, including Japan, the Korean states of Later Baekje, Goryeo, and Silla, and the Khitan-led Liao Dynasty. Buddhism played a crucial role in these interactions, as Japanese, Korean, and Chinese monks would regularly and freely travel between the three countries.

It was only in 978, when the reigning King Qian Chu faced certain annihilation from the Song Dynasty’s troops, that he finally submitted and pledged his allegiance to the Song in order to spare his people from war. While Wuyue was absorbed into the Song Empire, Qian Chu nominally remained king until his death in 988. Many shrines dedicated to the Qian royal family were erected throughout the region as a testament to the positive impact of their rule, the most popular of which is the one near West Lake in Hangzhou.

In spite of being dominated by the Song, the Kingdom of Wuyue cemented the Wuyue region’s status as a cultural and economic centre in China for centuries to come. The cultural distinctiveness of the region is still palpable today, with locals speaking a dialect of Chinese known as Wu, which is unintelligible to Mandarin Chinese speakers. On top of this, the Kingdom of Wuyue left behind a physical legacy in the form of stunning Buddhist temples, towering pagodas, and complex canal systems.