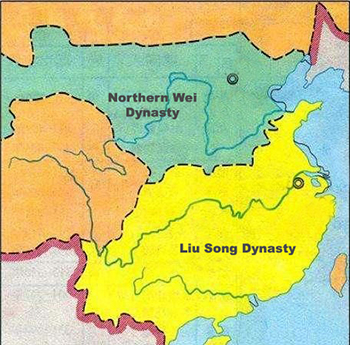

During the Sixteen Kingdoms Period (304-439), a time when the north of China was ravaged by numerous warring states, the Tuoba clan established the Northern Wei Dynasty (386–535). Like many rulers of the time, the Tuoba clan were descended from northern nomads who had immigrated to China, specifically the Xianbei people. However, this imposing dynasty didn’t begin its rise to prominence until 439, when Emperor Taiwu annexed all of the northern territories and effectively ended the Sixteen Kingdoms Period. With the north of China united under one ruling family, the Northern Wei had no choice but to turn their gaze south. Yet the Southern Dynasties would prove to be powerful nemeses, and the political stalemate between the North and the South would last for over 100 years. In short, this was a North-South divide to end all North-South divides!

Emperor Taiwu masterminded numerous expeditions against the southern Liu Song Dynasty (420–479) but, because of harassment from the Mongol-led Rouran Khaganate (330–555) in the north, he could not focus all of his efforts on vanquishing his southern rivals. His descendants would try numerous times to succeed where he had failed, but none of them would manage to make any significant territorial gains in the south.

Emperor Taiwu masterminded numerous expeditions against the southern Liu Song Dynasty (420–479) but, because of harassment from the Mongol-led Rouran Khaganate (330–555) in the north, he could not focus all of his efforts on vanquishing his southern rivals. His descendants would try numerous times to succeed where he had failed, but none of them would manage to make any significant territorial gains in the south.

It wasn’t until the ascension of Emperor Xiaowen (r. 471-499) that major changes began to take place in the imperial court. Up until his reign, Han Chinese subjects had been employed as officials, but only Xianbei tribesmen were allowed into positions of higher power. However, Emperor Xiaowen’s loyalties were torn, since his father was of Xianbei descent and his mother was Han Chinese. He was distinctly passionate about his dual Xianbei-Chinese identity and began a Sinification campaign in 493, which dictated that Xianbei nobles had to conform to certain Chinese standards.

These included banning traditional Xianbei dress at court, compulsory learning of the Chinese language for anyone under the age of thirty, applying one-character Chinese surnames to Xianbei families, and the encouragement of Xianbei-Chinese intermarriage. In one final act of severance from his Xianbei heritage, he even changed his own family name to “Yuan”, thus adhering to the Chinese tradition of single character surnames. This growing Chinese influence eventually seeped its way into the upper echelons of the imperial court, where the need for Han Chinese administrative methods and advisors grew.

Emperor Xiaowen also used the foreign religion of Buddhism to legitimise his rule, erecting large statues of Buddha near Pingcheng and declaring that the Northern Wei imperials were the representatives of Buddha. During this time, numerous Buddhist temples were constructed, as well as the magnificent Longmen Grottoes at Luoyang and Yungang Grottoes at Datong. As time went on, Xianbei customs were gradually abandoned.

The Emperor ultimately decided to move the imperial capital from Pingcheng to Luoyang, and roughly 150,000 Xianbei soldiers were forced to move there. However, many military men were left behind in northern garrison towns. Serving in these garrisons had once been a prestigious honour, as defending the empire against the Rouran Khaganate was paramount during the early years of the dynasty. However, after Emperor Xiaowen’s Sinification campaign, these Xianbei warrior families were stripped of their privileges and largely regarded as lower class citizens. As a result, they felt great hostility towards their aristocratic kinsmen.

In 523, they were pushed over the edge by a food shortage and began a fierce rebellion that would last for over a decade! Meanwhile, the empire was under the control of Empress Dowager Hu, who was manipulating her son, Emperor Xiaoming. In 528, when Emperor Xiaoming came of age and began criticising his mother’s handling of the rebellion, she had him poisoned. Not exactly the paragon of motherhood! Ironically, prior to Empress Dowager Hu’s rise to power, all Northern Wei empresses and concubines who gave birth to a boy would be immediately put to death, so as to ensure they would never interfere with their son’s reign. This law was only abolished by Empress Dowager Hu’s husband, Emperor Xuanwu, because of his devout dedication to Buddhism. If it hadn’t been for Emperor Xuanwu’s compassion, perhaps Emperor Xiaoming would have survived into adulthood.

Upon hearing of the Emperor’s death, General Erzhu Rong tricked the Empress Dowager into meeting him on the pretence of choosing the next emperor. On arrival, he butchered an estimated 2,000 city officials and had Empress Dowager Hu, along with her puppet child emperor Yuan Zhao, thrown into the Yellow River. Talk about taking drastic action! Erzhu placed Emperor Xiaozhuang on the throne, but continued to control the empire from behind the scenes. However, Emperor Xiaozhuang was naturally suspicious of Erzhu, since he had already thrown one emperor into a river! In 530, his arranged assassination of Erzhu prompted a civil war between the Erzhu Family and the imperial court. It was the Erzhu clan who came out on top, but numerous others continued to resist their rule.

Included among these rebels was a military general named Gao Huan, who had once been a top lieutenant under the Erzhu clan. Gao Huan was appalled by the Erzhu clan’s brutality, and the Erzhu clan were simultaneously aware that Gao Huan wielded great military power. Gao knew that he must gather his troops before the Erzhu clan made the first move. In 532, he amassed an army and occupied the capital of Luoyang. Confident in his power, he enthroned the puppet ruler Emperor Xiaowu before continuing his military campaigns, but the Emperor soon began plotting against him. When the Emperor’s plans were eventually foiled, he fled west to a region ruled by a formidable warlord named Yuwen Tai.

In 534, Gao Huan moved the imperial capital from Luoyang to the city of Ye or Yecheng and placed Emperor Xiaojing on the throne, thus founding the Eastern Wei Dynasty (534–550). Meanwhile, after having killed Emperor Xiaowu over a dispute, Yuwen Tai re-established the imperial capital of Chang’an (modern-day Xi’an) and instated Yuan Baoju as Emperor Wen of the Western Wei Dynasty (535–557). In this way, the Northern Wei Dynasty was severed between two rival claimants.

Although Gao Huan and Yuwen Tai were content to rule vicariously through their puppet emperors, it seemed that their sons were not. In 551, Gao Yang forced Emperor Xiaojing to abdicate and took the throne for himself, founding the Northern Qi Dynasty (551–577). In an almost identical power-play, Yuwen Jue seized power from Emperor Gong of Western Wei and established the Northern Zhou Dynasty (557–580). Although Northern Qi was the most powerful of the dynasties at the time, it was swiftly weakened by corrupt officials and a sequence of incompetent rulers. Thanks to the concerted efforts of Emperor Wu, the Northern Zhou Dynasty was finally able to conquer the Northern Qi in 577. Unfortunately, like many victories in this turbulent period, it would be fleeting.

Emperor Xuan, the grandson of Yuwen Tai, proved to be an erratic leader and the Northern Zhou Dynasty deteriorated under his reign. His father-in-law, Yang Jian, took advantage of his death in 580 and seized power, eventually overthrowing the reigning Emperor Jing and establishing himself as Emperor Wen of the Sui Dynasty (581-618). In a bold and malicious move, he then slaughtered all members of the imperial Yuwen family. Yet cruel though Yang may have been, he did manage to succeed where all of the northern rulers had failed.

Through the use of military power, public morale, and convincing propaganda, he was able to conquer the Chen Dynasty (557–589) in the south and thus successfully re-united China. Though the Sui Dynasty may not have lasted long, they brought into effect a golden age of centralised rule that continued throughout the succeeding Tang Dynasty (618–907).

One Reply to “The Northern Dynasties”

Comments are closed.