The sleepy town of Shaxi near the Heihui River is a far cry from what it once was. However, go there any given Friday and you’ll be met with the bustling local market, the last remnant of a trading culture that has all but disappeared in modern-day China. Like Dali Ancient Town and Shuhe Town, Shaxi once prospered thanks to the ancient Tea-Horse Road but, unlike its local counterparts, it has not yet suffered from the commercialisation that tourist towns inevitably succumb to. Though Shaxi boasts a few Western-style restaurants and boutique hotels, its relative inaccessibility compared to many of the other ancient towns in Yunnan means it does not receive the hordes of tourists that can make these spots a little less magical.

During the Tang Dynasty (618-907), Shaxi became one of the focal trade hubs along the Tea-Horse Road and by the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1912) dynasties it had flourished into one of the most affluent towns in Yunnan. Shaxi’s success largely arose from the salt wells that were dug near the town. It soon became the salt trade capital and, with salt being one of the most valuable commodities at the time, it prospered far beyond expectation. Revenge may be sweet, but success is evidently salty! This allowed the town to expand and many of the elaborate buildings found throughout Shaxi were erected during this time.

The town is largely inhabited by the Bai ethnic minority and many of its old buildings follow the Bai-style of “three rooms and one wall screening”. The house will usually consist of one main room, two side rooms and a “shining wall” that faces west so as to reflect light back into the house at sunset. The houses normally have three storeys in total and nine rooms, as nine is an auspicious number in Bai culture. The ground floor usually consists of one large sitting room flanked by two bedrooms, while the upper floors are used for storage with a special room set aside for the ancestral shrine.

Life in Shaxi mainly revolves around Square Street, the town’s central square. This ancient plaza is covered in red sand bricks and has two Chinese scholar trees standing at its centre that are each centuries old. It is still fully functioning on market day and is surrounded by a number of small temples, shops, teahouses and restaurants. It is flanked on its east side by an ancient stage and on its west by the 600-year-old Xingjiao Temple. The many ancient alleyways that branch out from Square Street are the backbone of Shaxi and provide access to its outer reaches. They lead to the village gates and pass by ancient caravansaries, eventually heading out towards Dali, Tibet and the salt wells.

The ancient stage is widely considered to be the heart and soul of Shaxi. The craftsmanship with which it was made is palpable in its many intricate carvings. It was built during the Qing Dynasty and is part of the three-storey Kuixing Pavilion. If you pay 10 yuan (about £1), you can ascend the ancient stage and head up to an exhibition of locally excavated cultural relics on the pavilion’s second storey. Just don’t linger too long on the stage, or the locals might expect a performance from you!

If you fancy getting in touch with the town’s history, you should certainly take a trip to Ouyang House. It was one of the original caravansaries and has been home to generations of muleteers over a period of one hundred years. In the early 1900s, the Ouyang family opened their house to passing caravans and offered food, lodgings and entertainment. They swiftly became the leading innkeepers in Shaxi and their substantial income enabled them to renovate and extend their inn. Nowadays, you can pay just 5 yuan (about 50p) to take a tour of the house and marvel at its ancient stables, guest quarters, kitchen, and ancestral shrine.

In spite of all these visual wonders, the must-see attraction in Shaxi is the town market, which has supposedly been held weekly since 1415. Although it started as a small affair, it has now become an all-consuming venture that billows out from the town square and floods the streets of Shaxi every week. From 10am till 5pm every Friday, goods ranging from washing machines to embroidered shoes and exotic fruits can be purchased at this eclectic market. It is a living remnant of Shaxi’s history as a trading post and is a spectacle of vibrancy, colour and animation that should not be missed.

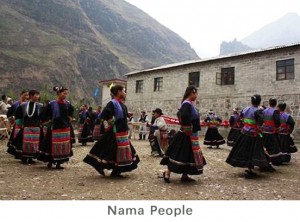

Not far from the town you’ll find Mount Shibao, which is a mountain that has been delicately engraved with Buddhist carvings that date back to the 7th century. These 1,300-year-old carvings, punctuated by small temples along the mountainside, are truly stunning and make for a wonderful day out. If you decide to cycle out of the town, there are many small Bai and Yi villages in the Shaxi Valley that are only a short distance away and each boast their own unique attractions, from the renovated Pear Orchard Temple in Diantou Village to the Kuixing Pavilion of Changle Village.

If possible, we recommend you aim to catch the Temple Fair of Prince Shakyamuni, which takes place on the 8th day of the 2nd month according to the Chinese lunar calendar. During this festival, locals in colourful traditional clothes gather at Xingjiao Temple and parade through the streets carrying statues of Shakyamuni[1], while a team of people beat gongs and drums to liven up the procession. Performances will take place on the ancient stage throughout the festival and the celebrations carry on late into the night, electrifying the town square with bright lights, lively music and joyous dancing.

[1] Shakyamuni: One of the titles of Gautama Buddha, the central figure of the Buddhist faith. It is derived from the name Sakya, which is where he was born.