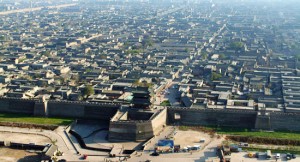

At the grand age of 2,700 years, Pingyao is one of the oldest cities in China and was once the financial centre of the entire country. The city was established during the reign of King Xuan (827-782 BC) of the Western Zhou Dynasty (c. 1046–771 BC), although it had to be largely rebuilt in 1370, during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644). It was during this time that the city was expanded and its famed city walls were constructed. By the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912), it was home to more than 20 financial institutions, which represented more than half of the total number in the entirety of China.

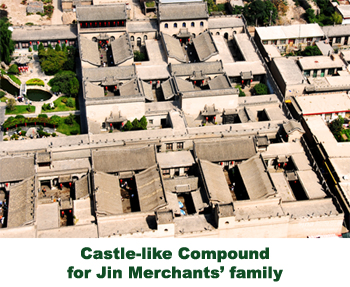

The Jin merchants who owned these institutions swiftly rose to prominence and became the most important economic influence on Shanxi province. You could say their sudden wealth meant they were laughing all the way to the bank! Nowadays it is home to some of the most well-preserved ancient structures in the country, many of which are located on its picturesque Ming-Qing Street, and it was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1997.

The City Walls

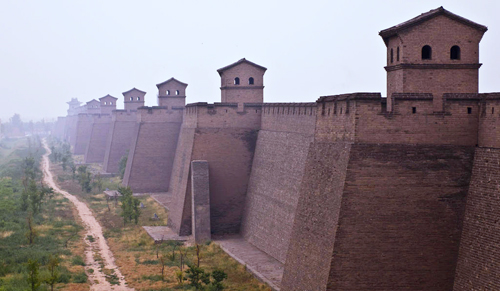

The city was built according to the typical layout of ancient Chinese towns, but also conformed to a traditional theory known as Bagua or the “Eight Trigrams”. To this end, the temples and government offices were located on both sides of the central axis, while the residential houses and commercial markets were in the town centre. This layout has been retained to this day, and the city is still home to some 50,000 residents. The ancient part of the city is surrounded by the city walls, which are 12 metres (39 ft.) high and stretch for 6 kilometres (4 mi) in length! The wall itself is heavily fortified, with four towers at its corners, 72 watchtowers, over 3,000 battlements, and a 4-metre (13 ft.) deep moat at its feet.

The walls are punctuated by six barbican gates in total, with one each on the north and south sides, and two each on the west and east sides. From an aerial perspective, this supposedly makes Pingyao look like a tortoise, with the west and east gates as the legs, the north gate as the tail, the south gate as the head, and the criss-crossing lanes within as the patterns on its shell. This has earned it the nickname the “Tortoise City”!

The walls are punctuated by six barbican gates in total, with one each on the north and south sides, and two each on the west and east sides. From an aerial perspective, this supposedly makes Pingyao look like a tortoise, with the west and east gates as the legs, the north gate as the tail, the south gate as the head, and the criss-crossing lanes within as the patterns on its shell. This has earned it the nickname the “Tortoise City”!

This resemblance is no accident, as tortoises are a symbol of longevity in traditional Chinese culture. It was believed that, by having city walls in the shape of a tortoise, this would ensure that the city would remain secure in perpetuity. Much like the tortoise and the hare, the slow and steady pace in Pingyao meant it definitely won the race! The city walls are in such great condition that visitors can still take a leisurely stroll along them to this day.

Exchange Houses

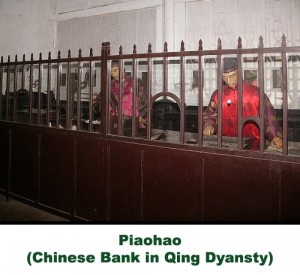

In ancient times, these city walls protected not only the people, but also the financial institutions that Pingyao eventually became famous for. Among these, the most renowned is known as Rishengchang or “Sunrise Prosperity”, which was established in 1823 and is thought to have been the first bank in China. During its heyday, Rishengchang controlled nearly half of the silver circulating in the country. It may have traded in silver, but it was worth its weight in gold!

The need for piaohao or “exchange houses” such as Rishengchang arose when traders began using silver coins during the Ming and Qing dynasties. Rampant banditry meant it was unsafe for merchants to carry large sums of silver with them as they travelled, so these exchange houses were able to provide money transfers, accept deposits, and give out loans. While Rishengchang’s base was in Pingyao, it founded branches in major cities throughout China, Japan, Singapore, and Russia, and used bank drafts to move money from one branch to another.

It managed to maintain its prosperity for a staggering 109 years, until it tragically went bankrupt in 1932 due to the advent of modern banking. The development of Rishengchang is considered so integral to the economic history of China that its original head office was restored and converted into a museum in 1995. It was even immortalised in the 2009 film Empire of Silver, about a wealthy banking family living in Pingyao during the turn of the 20th century. From the silver trade to the silver screen, Rishengchang was destined to shine! (Find more stories about Jin Merchants.)

Temple of the City God

Alongside the city walls and Rishengchang, the other major attractions within the ancient city are the County Government Office and the Temple of the City God. While the County Government Office was designed to rule the “yang” of the human world, the Temple of the City God held sway over the “yin” of the spiritual world. These two buildings were placed on the same street in order to balance each other out, with the office in the west and the temple in the east. The County Government Office was originally built in 1346, during the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368), and is the largest of its kind in China. It represented a vast complex containing the home of the local magistrate, various offices, a prison, a court, meeting rooms, and a scenic garden.

Alongside the city walls and Rishengchang, the other major attractions within the ancient city are the County Government Office and the Temple of the City God. While the County Government Office was designed to rule the “yang” of the human world, the Temple of the City God held sway over the “yin” of the spiritual world. These two buildings were placed on the same street in order to balance each other out, with the office in the west and the temple in the east. The County Government Office was originally built in 1346, during the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368), and is the largest of its kind in China. It represented a vast complex containing the home of the local magistrate, various offices, a prison, a court, meeting rooms, and a scenic garden.

In the same vein, the Temple of the City God is comprised of several decorative courtyards and magnificent halls. This Taoist temple was constructed during the Song Dynasty (960-1279) and, unlike other city god temples in China, it honours the God of Wealth and the Kitchen God as well as the City God of Pingyao. While it is a popular tourist attraction in the city, it should be noted that it remains an active house of worship and is frequently visited by residents eager to appease their local deity!

Outside the city walls, two other temples have been included as part of the UNESCO World Heritage Site: Shuanglin Temple and Zhenguo Temple. Shuanglin Temple was built in 571 AD and is renowned for the more than 2,000 coloured clay statues that bedeck its halls, which were crafted between the 13th and 17th centuries. Similarly, Zhenguo Temple was constructed in 963 AD and boasts a number of magnificent sculptures that date all the way back to the Northern Han Dynasty (951–979). In short, Pingyao may not have the notoriety of the Great Wall or the Forbidden City, but its historical pedigree is beyond compare!

Join a travel with us to explore more about Pingyao Old Town: Explore Chinese Culture through the Ages