Since Jiangsu or “Su” cuisine is often praised as one of the Eight Culinary Traditions of Chinese Cooking, it goes without saying that the snacks on offer in this province are plentiful and delicious! This style of cooking places emphasis on presentation and the natural essence of ingredients, resulting in dishes that are visually stunning and richly flavourful without being overly seasoned. Soups play a starring role in most snack dishes and are highly acclaimed for being light and fresh, rather than oily or greasy. With palate-cleansers that are this scrumptious, you might even forget about the main course!

Also known as Yangzhou Egg Fried Rice, this staple dish hails from the city of Yangzhou and is one of the most immediately recognisable dishes in Jiangsu, since it’s served in Chinese restaurants throughout the world. The ingredients of this hearty dish vary from restaurant to restaurant, but some of the staple items include: cooked rice that is preferably a day old, since freshly cooked rice is often too sticky; cooked shrimp; diced char siu or Chinese barbecue pork; chopped spring onions; eggs; and fresh vegetables such as peas, Chinese broccoli, carrots, and corn. Like glittering jewels in a fine brooch, these multi-coloured ingredients add a touch of vibrancy to the dish.

According to local legend, the dish was brought to the region during the Sui Dynasty (581-618) by a powerful imperial minister named Yang Su. Fried rice was one of his favourite foods and, when he was escorting Emperor Yangdi through the district of Jiangdu, he introduced his recipe to the people of Yangzhou. There are two ways of cooking this sumptuous dish based on when and how the egg is scrambled. The first, known as “silver covering gold”, is when the egg is scrambled separately and then mixed in with the rice. The second, known as “gold covering silver”, is when the liquid egg is poured over the rice and vegetables as they are being stir-fried. It’s rumoured that the finest chefs in Yangzhou can cook the dish with a rice grain to egg piece ratio of 5:1 or even 3:1. Talk about precise!

Shaomai or shumai in Chinese cuisine is a traditional type of bite-size pork dumpling served as dim sum. They’re living proof that good things definitely come in small packages! They are believed to have originated from the city of Hohhot in Inner Mongolia, but the ones served in the Jiangnan region of Jiangsu, just south of the Yangtze River, are considerably different to their northern counterparts. In this variation, the wrapping for the dumpling is much larger and tougher. The filling is made up of glutinous rice and pork pieces that have been marinated in a delectable mixture of Chinese rice wine (Shaoxing wine) and soy sauce. They are normally steamed with pork fat to keep them tantalisingly moist and are markedly larger than other types of shaomai. Most restaurants typically serve them as an appetising accompaniment to a cup of tea. Once you’ve tried these juicy little parcels, you’ll never look at afternoon tea the same way again!

These enticingly aromatic noodles originate from Fengqiao Town in Suzhou and are said to have the fragrance of rice wine. So be sure not to breathe in too deeply, or you might end up drunk! The delicate noodles are first boiled before being served in a light broth made from stewed eel bones, river snails, rice wine, and soy sauce. However, the highlight of this dish is considered to be the topping. Thick, streaky slices of pork are marinated in rice wine and stewed for at least four hours before being used as a garnish. The resulting dish is an ideal combination of subtle flavours that melt in the mouth and glance off the tongue. Fengzhen Noodles are typically served during summer, as they are believed to cool the palate during the hotter weather. So if you’re traveling in Jiangsu, be sure to use your noodle and order a bowl of this tasty treat!

Sesame seed cakes are thought to be the oldest style of cake in Jiangsu and the earliest record of them, written by an agronomist named Jia Sixie, dates all the way back to the Northern Wei Dynasty (386–535). So it seems the locals have had plenty of time to perfect the recipe! Unsurprisingly, this particular type of sesame cake originates from the town of Huangqiao. According to local legend, sometime during the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912), the magistrate of Rugao County was visiting the region when he tried a few of these crispy cakes. On returning home, he was so taken with them that he began getting serious cravings. Unfortunately, the counties were over 30 kilometres (19 mi) and it seemed impractical to go all that way just for a snack. So he sent one of his servants to buy the cakes for him instead!

The cakes themselves come in a variety of shapes and sizes, from the typical round and oval ones right through to triangular and square ones. Unlike conventional cakes in the West, Huangqiao sesame cakes come in sweet and savoury varieties. This means the basic dough can vary, as sweet dough incorporates caramel while savoury dough includes pork suet and onion. More sophisticated varieties of this crunchy snack include fillings such as pork, sweet osmanthus paste, crab roe, jujube paste, chicken, and shrimp. So, if you happen to spot a tray full of these fluffy treats, choosing one can feel like a game of roulette!

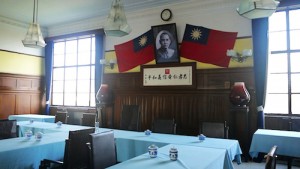

Having served as the capital for 7 separate kingdoms, one dynasty, and one revolutionary government, Nanjing is a city steeped in history and is now ranked as one of the Four Great Ancient Capitals of China. It was also the capital of the Republic of China from 1927 to 1949. As a testament to its ancient roots, it is still surrounded by a 48-kilometre-long (30 mi) city wall, which was constructed during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644). Nowadays it serves as the provincial capital of Jiangsu province, but its long and illustrious history is flecked with success and tragedy.

Having served as the capital for 7 separate kingdoms, one dynasty, and one revolutionary government, Nanjing is a city steeped in history and is now ranked as one of the Four Great Ancient Capitals of China. It was also the capital of the Republic of China from 1927 to 1949. As a testament to its ancient roots, it is still surrounded by a 48-kilometre-long (30 mi) city wall, which was constructed during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644). Nowadays it serves as the provincial capital of Jiangsu province, but its long and illustrious history is flecked with success and tragedy. In 1421, the Yongle Emperor moved the capital to Beijing but maintained the importance of Yingtianfu, renaming it “Nanping” or “Southern Capital” and making it the country’s subsidiary capital. During the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912), it was again renamed to Jiangning and, with all of these name changes, it’s a small wonder the locals ever knew what to call it! From then onwards, the city would unfortunately be racked by warfare. In 1853 it was occupied by the revolutionary forces of the Taiping Rebellion and was made the capital of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom (1851–1864), enduring another name change as Tianjing or “The Heavenly Capital”.

In 1421, the Yongle Emperor moved the capital to Beijing but maintained the importance of Yingtianfu, renaming it “Nanping” or “Southern Capital” and making it the country’s subsidiary capital. During the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912), it was again renamed to Jiangning and, with all of these name changes, it’s a small wonder the locals ever knew what to call it! From then onwards, the city would unfortunately be racked by warfare. In 1853 it was occupied by the revolutionary forces of the Taiping Rebellion and was made the capital of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom (1851–1864), enduring another name change as Tianjing or “The Heavenly Capital”.