Nestled within a river valley in the town of Gyantse in Shigatse Prefecture, Tibet, the Palcho Monastery represents an unusual intermingling of faiths. Sometimes referred to as the Pelkor Chode Monastery, this venerable place of worship is one of the only monasteries that incorporates teachings from multiple sects of Tibetan Buddhism. Within its walls, you’ll find artwork and scriptures dedicated to the Sakya, Gelug, and Kagyu sects of Tibetan Buddhism.

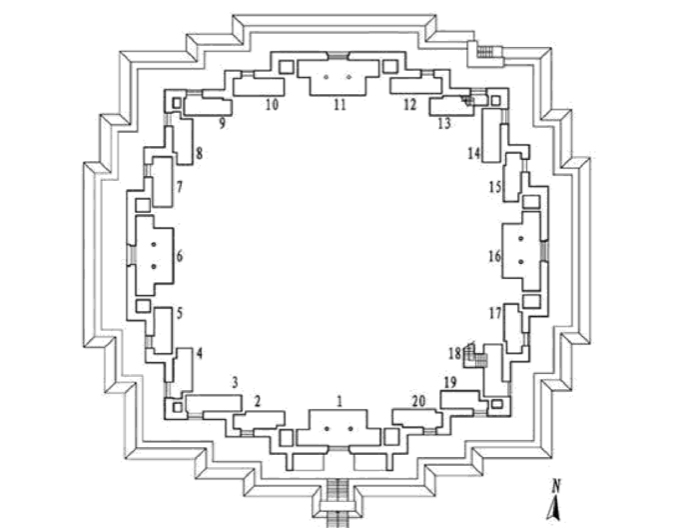

The main temple of the monastery complex is known as Tsuklakhang and was built sometime between 1418 and 1425. This three-storey building follows the typical Tibetan style of architecture. The ground floor has been divided into three parts: the front hall, the main hall and the back hall. There is a Dharmapāla[1] chapel on the right side of the front hall and a Buddha chapel on its left side. The main hall is where the monks study and chant, and is supported by a sequence of 48 colossal pillars.

Within this hall, there is a spectacular 8-metre-tall bronze statue of the Buddha that is the main subject of worship. Like the front hall, there are also two small chapels on either side of the main hall. The back hall, by contrast, is much smaller and is only supported by 8 pillars. It also contains a bronze statue of Buddha as its main subject of worship. There are another 5 chapels on the first floor and one large chapel on the top floor, which is home to a series of breathtakingly beautiful murals. Once the temple was originally completed, it became an important monastery for the Sakya sect of Tibetan Buddhism.

In 1427, the Tibetan noble Rabten Kunzang Phak donated vast sums of money in order to expand the monastery, which led to the addition of what’s known as a Kumbum[2] and a few other buildings. This colossal construction project was led by a monk named Khedrup Je, who was posthumously recognised as the first Panchen Lama. The Kumbum at the Palcho Monastery rose to become not only the most prominent of its kind in Gyatse, but also the most famous Kumbum in Tibet. This particular Kumbum is made up of a staggering ten storeys. From the first floor to the ninth floor, you will find 76 chapels with 108 doors. Each chapel contains a variety of stunning Buddhist statues. You can recognize the artistic value of each and every statue simply by looking at the vivid facial expressions of the figures being portrayed. Thanks to this expansive statue collection, this Kumbum is sometimes referred to as the “Hundred Thousand Buddha Stupa.”

Alongside the statues, the murals are another invaluable and celebrated artistic asset of the Palcho Monastery. They can be found throughout every chapel of the Kumbum and in every room of the main temple. The murals in the main temple were painted following a deliberate and carefully planned design, which was based around the function of the hall and who would typically be worshipping within it. For example, in the main hall you will find the three main Buddhas associated with Buddhism: Gautama Buddha, Dīpankara Buddha[3] and Maitreya Buddha [4]. The murals in the Kumbum are mainly dedicated to depicting stories from the Vajrayāna sect of Buddhism [5].

Throughout its long history, the Palcho Monastery has suffered through three major catastrophes. In 1904, a British expedition decided to infiltrate Lhasa via Gyantse. After about 100 days of warfare, the people of Gyantse were unable to prevent this invasion. The British expedition therefore captured Gyantse and decided to make the Palcho Monastery their temporary military base, which caused a huge amount of damage to the interior. The second catastrophe that caused colossal damage to the monastery happened during the 1959 Tibetan Uprising, the event which prompted the 14th Dalai Lama to flee to India. The final catastrophe came only ten years later, when the monastery was ransacked during the Cultural Revolution.

Fortunately, the entire monastery has been restored and the restoration project did a wonderful job of repairing the damage. Nowadays, when you visit the monastery, you will still be struck by its vibrancy and beauty. You may find, however, that the colour on some of the murals has changed due to the burning of the ceremonial butter lamps. This is not a scar left by historical atrocities, but is simply a mark of time and religious devotion.

[1] A Dharmapāla is a type of wrathful god in Buddhism.

[2] A Kumbum is a multi-storied stūpa of Buddhist chapels in Tibetan Buddhism.

[3] Dīpankara is one of the Buddhas of the past.

[4] Maitreya is regarded as the future Buddha.

[5] The term Vajrayāna is used to refer to one of the major sects of Buddhism, which is sometimes known as the Tantric sect. It mainly focuses on the chanting of mantras, the use of special gestures known as mudras, and visualization methods with the help of paintings called mandalas.

Make your dream trip to the Palcho Monastery come true on our travel: Explore Untouched Wilderness on Our Full Circuit of Tibet

The practice of giving hada is so centric to Tibetan culture that, whenever a person leaves the house, they will carry several hada with them in case an opportunity arises where they might be expected to offer one. When writing letters, they will even enclose a miniature hada in the envelope! In most contexts, the hada is designed to extend good wishes and respect, but its significance may change slightly depending on the context. During festivals, a hada is exchanged to wish the recipient a happy holiday. At weddings, the bride and groom are presented with hada in the hopes that they will have everlasting harmony and a bright future together. At funerals, the family present hada to the guests so that the Buddha may bless them and the guests offer hada to the grieving relatives in order to express their condolences.

The practice of giving hada is so centric to Tibetan culture that, whenever a person leaves the house, they will carry several hada with them in case an opportunity arises where they might be expected to offer one. When writing letters, they will even enclose a miniature hada in the envelope! In most contexts, the hada is designed to extend good wishes and respect, but its significance may change slightly depending on the context. During festivals, a hada is exchanged to wish the recipient a happy holiday. At weddings, the bride and groom are presented with hada in the hopes that they will have everlasting harmony and a bright future together. At funerals, the family present hada to the guests so that the Buddha may bless them and the guests offer hada to the grieving relatives in order to express their condolences.

Living primarily in isolated locations throughout India, Nepal, Bhutan, and the Tibet Autonomous Region of China, the Tibetan people have maintained an air of mystery that has captured the curiosity of people throughout the world. They embody a culture defined by spirituality, communion with nature, and rigid discipline. Even their language is highly stylised, with honorific and ordinary versions for most words, which are used to address superiors or inferiors respectively. The indisputable importance that religion holds for Tibetans is reflected in this language, as there is a set of higher honorific terms that are only to be used when addressing the highest sect of Buddhist lamas.

Living primarily in isolated locations throughout India, Nepal, Bhutan, and the Tibet Autonomous Region of China, the Tibetan people have maintained an air of mystery that has captured the curiosity of people throughout the world. They embody a culture defined by spirituality, communion with nature, and rigid discipline. Even their language is highly stylised, with honorific and ordinary versions for most words, which are used to address superiors or inferiors respectively. The indisputable importance that religion holds for Tibetans is reflected in this language, as there is a set of higher honorific terms that are only to be used when addressing the highest sect of Buddhist lamas.