Long ago, when the earth was in its infancy, there roamed a mythical monkey known as Pha Trelgen Changchup Sempa. Even his name was imbued with deep significance, with “pha” meaning “father”, “trelgen” meaning “old monkey”, “changchup” translating to “enlightenment”, and “sempa” meaning “intention”. He settled on Mount Gongori in Tibet, where he vowed to immerse himself in meditation and pursue a life of asceticism. One day, while he sat deep in thought, he was approached by a rock ogress named Ma Drag Sinmo. She begged the monkey to marry her and made every attempt to seduce him, but he refused, as his religious discipline meant he could not yield to temptation.

In her desperation, the ogress then resorted to threats. She told the monkey that, if he would not marry her, then she would marry a demon and produce a multitude of smaller monsters, which would overrun the earth and destroy all other living creatures. Evidently she didn’t take rejection very well! The monkey despaired and, not knowing what to do, he consulted the bodhisattva[1] Avalokiteśvara. Avalokiteśvara told the monkey that this was an auspicious sign and that he was destined to marry the ogress, so he gave the couple his blessing and the two were married.

Within a few months, the ogress gave birth to six small monkeys and the elder monkey left his six children to grow up in the forest. After three years, he returned and, to his dismay, he found that they had multiplied to five hundred monkeys. The fruits of the forest were no longer enough to sustain them, and they beseeched their father to help them find food. At a loss once again, the elder monkey went back to Avalokiteśvara. The bodhisattva travelled to the sacred Mount Meru, but from here the story diverges. Some say he collected a handful of barley on the mountain, while others believe he plucked the five cereals from his own body and offered them to the elder monkey.

Regardless of how it transpired, the elder monkey planted the cereals and, after a bumper harvest, he was able to feed all of his children. As they continued to engage in agriculture and move away from the forest, the monkeys gradually lost their tails and most of their hair. They began to use tools made from bone and stone, then wove their own clothes and built their own houses. Eventually they formed a venerable civilisation, from which the Tibetan people supposedly descended. So the next time you question your own family tree, imagine how strange it would be to have a monkey and an ogress as your ancestors!

Living primarily in isolated locations throughout India, Nepal, Bhutan, and the Tibet Autonomous Region of China, the Tibetan people have maintained an air of mystery that has captured the curiosity of people throughout the world. They embody a culture defined by spirituality, communion with nature, and rigid discipline. Even their language is highly stylised, with honorific and ordinary versions for most words, which are used to address superiors or inferiors respectively. The indisputable importance that religion holds for Tibetans is reflected in this language, as there is a set of higher honorific terms that are only to be used when addressing the highest sect of Buddhist lamas.

Living primarily in isolated locations throughout India, Nepal, Bhutan, and the Tibet Autonomous Region of China, the Tibetan people have maintained an air of mystery that has captured the curiosity of people throughout the world. They embody a culture defined by spirituality, communion with nature, and rigid discipline. Even their language is highly stylised, with honorific and ordinary versions for most words, which are used to address superiors or inferiors respectively. The indisputable importance that religion holds for Tibetans is reflected in this language, as there is a set of higher honorific terms that are only to be used when addressing the highest sect of Buddhist lamas.

According to historical records, it is estimated that the ancestors of the Tibetan people began settling along the Yarlung Tsangpo River sometime before the Qin Dynasty (221-206 BC). The expansive grasslands and lush pastures allowed them to easily raise and support herds of sheep, goat, and yak, which became their primary source of income. However, the harsh climate meant they could only grow certain hardier varieties of grain, such as highland barley. Thus they evolved into an ethnic group primarily composed of farmers and pastoral nomads, with a clear distinction between peasantry and the elite landowning class.

Their belief in and devotion to a higher power first manifested in the indigenous religion of Bön, which was gradually superseded by Buddhism during the 7th century. Eventually these two venerable faiths intermingled to form Tibetan Buddhism, the religion observed by the majority of Tibetans to this day. From the darkened corridors and elaborately decorated halls of the Potala Palace to the humble yurts on the craggy Tibetan Plateau, people from all walks of life carry prayer wheels, chant sutras[2], and prostrate themselves as a demonstration of their piety.

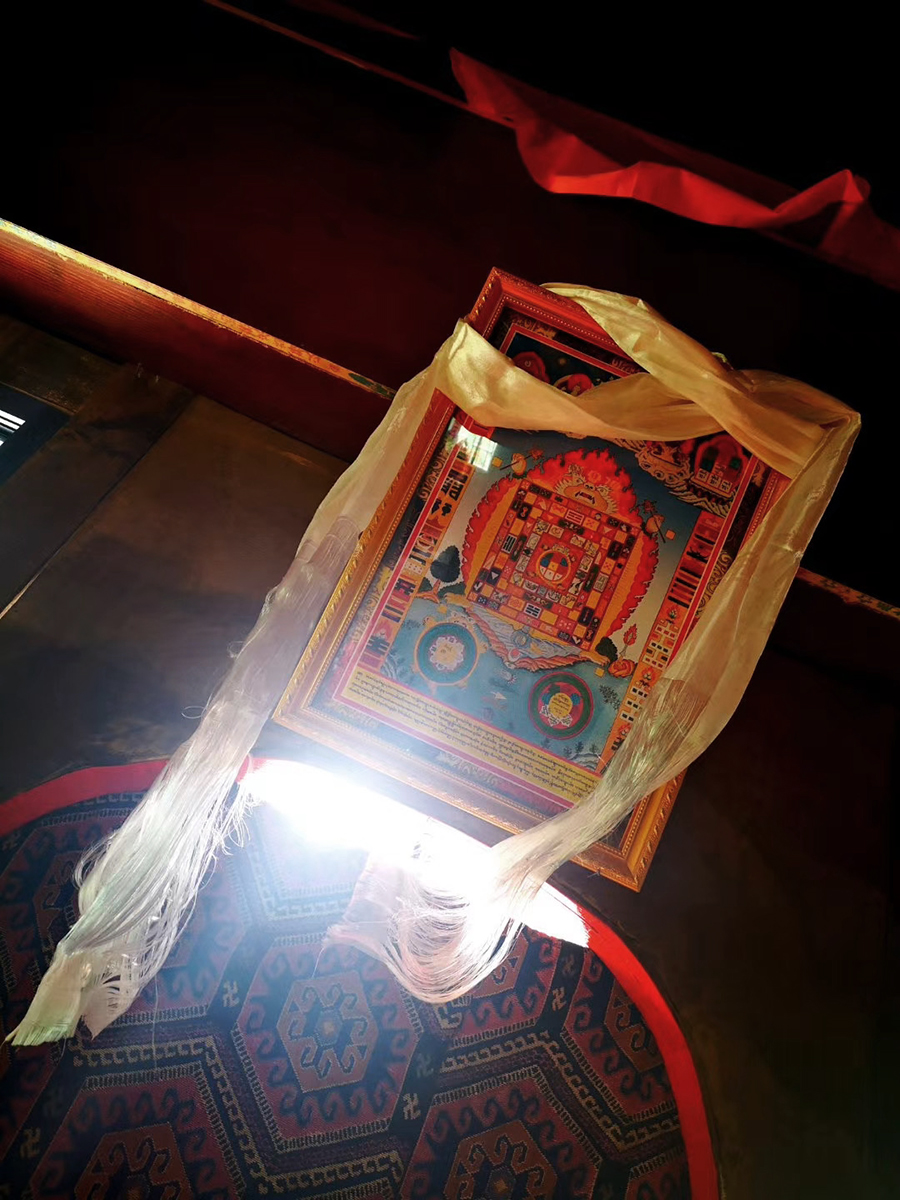

This extreme devoutness has given birth to countless stunning works of art, including intricate thangka paintings, elegant statuary, and the semi-spiritual Epic of King Gesar, which is considered to be the longest hero epic in the world. While this level of piousness might lead you to think that the Tibetan people are solemn, that’s far from the truth! Religious festivals, such as the Losar Festival and the Shoton Festival, are celebrated with lively performances of Tibetan Opera, singing, dancing, and bountiful feasts. With such a rich and vibrant culture, it’s easy to see how the lifestyle of this enigmatic ethnic group has captured the imaginations of people from across the globe.

[1] Bodhisattva: The term literally means “one whose goal is awakening”. It refers to a person who seeks enlightenment and is thus on the path to becoming a Buddha. It can be applied to anyone, from a newly inducted Buddhist to a veteran or “celestial” bodhisattva who has achieved supernatural powers through their training.

[2] Sutra: One of the sermons of the historical Buddha.

Read more about Tibetan Ethnic Minority:

Traditional Dress Other Customs

The practice of giving hada is so centric to Tibetan culture that, whenever a person leaves the house, they will carry several hada with them in case an opportunity arises where they might be expected to offer one. When writing letters, they will even enclose a miniature hada in the envelope! In most contexts, the hada is designed to extend good wishes and respect, but its significance may change slightly depending on the context. During festivals, a hada is exchanged to wish the recipient a happy holiday. At weddings, the bride and groom are presented with hada in the hopes that they will have everlasting harmony and a bright future together. At funerals, the family present hada to the guests so that the Buddha may bless them and the guests offer hada to the grieving relatives in order to express their condolences.

The practice of giving hada is so centric to Tibetan culture that, whenever a person leaves the house, they will carry several hada with them in case an opportunity arises where they might be expected to offer one. When writing letters, they will even enclose a miniature hada in the envelope! In most contexts, the hada is designed to extend good wishes and respect, but its significance may change slightly depending on the context. During festivals, a hada is exchanged to wish the recipient a happy holiday. At weddings, the bride and groom are presented with hada in the hopes that they will have everlasting harmony and a bright future together. At funerals, the family present hada to the guests so that the Buddha may bless them and the guests offer hada to the grieving relatives in order to express their condolences.

Living primarily in isolated locations throughout India, Nepal, Bhutan, and the Tibet Autonomous Region of China, the Tibetan people have maintained an air of mystery that has captured the curiosity of people throughout the world. They embody a culture defined by spirituality, communion with nature, and rigid discipline. Even their language is highly stylised, with honorific and ordinary versions for most words, which are used to address superiors or inferiors respectively. The indisputable importance that religion holds for Tibetans is reflected in this language, as there is a set of higher honorific terms that are only to be used when addressing the highest sect of Buddhist lamas.

Living primarily in isolated locations throughout India, Nepal, Bhutan, and the Tibet Autonomous Region of China, the Tibetan people have maintained an air of mystery that has captured the curiosity of people throughout the world. They embody a culture defined by spirituality, communion with nature, and rigid discipline. Even their language is highly stylised, with honorific and ordinary versions for most words, which are used to address superiors or inferiors respectively. The indisputable importance that religion holds for Tibetans is reflected in this language, as there is a set of higher honorific terms that are only to be used when addressing the highest sect of Buddhist lamas. In spite of the hostile environment in which they live, the traditional garments of the Tibetan people are defined by their bright colours and elaborate ornamentation. Like precious stones and glimmering jewels, they stand out on the barren plains of the Tibetan plateau. Tibetans typically don long-sleeved jackets made of silk or cloth, covered by a loose robe tied at the right by a band. Nomadic herdsmen and women working in colder climates eschew the jacket in favour of sheepskin robes fringed with fur. While women tend to wear skirts with a multi-coloured apron over top and men wear trousers, they both opt for leather long-boots to combat the rocky terrain and felt or fur hats to keep themselves warm. For the sake of mobility, many Tibetans leave one or both shoulders uncovered and tie the sleeves around their waist when they are working.

In spite of the hostile environment in which they live, the traditional garments of the Tibetan people are defined by their bright colours and elaborate ornamentation. Like precious stones and glimmering jewels, they stand out on the barren plains of the Tibetan plateau. Tibetans typically don long-sleeved jackets made of silk or cloth, covered by a loose robe tied at the right by a band. Nomadic herdsmen and women working in colder climates eschew the jacket in favour of sheepskin robes fringed with fur. While women tend to wear skirts with a multi-coloured apron over top and men wear trousers, they both opt for leather long-boots to combat the rocky terrain and felt or fur hats to keep themselves warm. For the sake of mobility, many Tibetans leave one or both shoulders uncovered and tie the sleeves around their waist when they are working.