Nestled within the Muslim Quarter in the city of Xi’an, the Great Mosque is the largest of its kind in China and, alongside being a popular tourist site, remains an active place of worship to this day. What makes this mosque particularly unique is that it combines traditional Chinese architectural features with Islamic ones, looking from the outside like a typical Chinese temple but bearing the hallmarks of an Islamic mosque within its interior. According to historical records engraved on a stone tablet within the complex, the original mosque was built on this site in 742 AD, during the Tang Dynasty (618-907). This mosque was built in order to accommodate the many merchants and travellers from Central Asia who settled in Xi’an, the then capital of China, and introduced Islam to the country.

The current mosque, however, was constructed in 1392, during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) and was renovated numerous times thereafter, meaning that many of the structures we find today date back to the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. At the time of its construction, the mosque lay just outside of the Ming Dynasty city walls in a neighbourhood that was designated for foreigners, but today this area has been incorporated into the city proper and can be found close to the city’s famed Drum Tower.

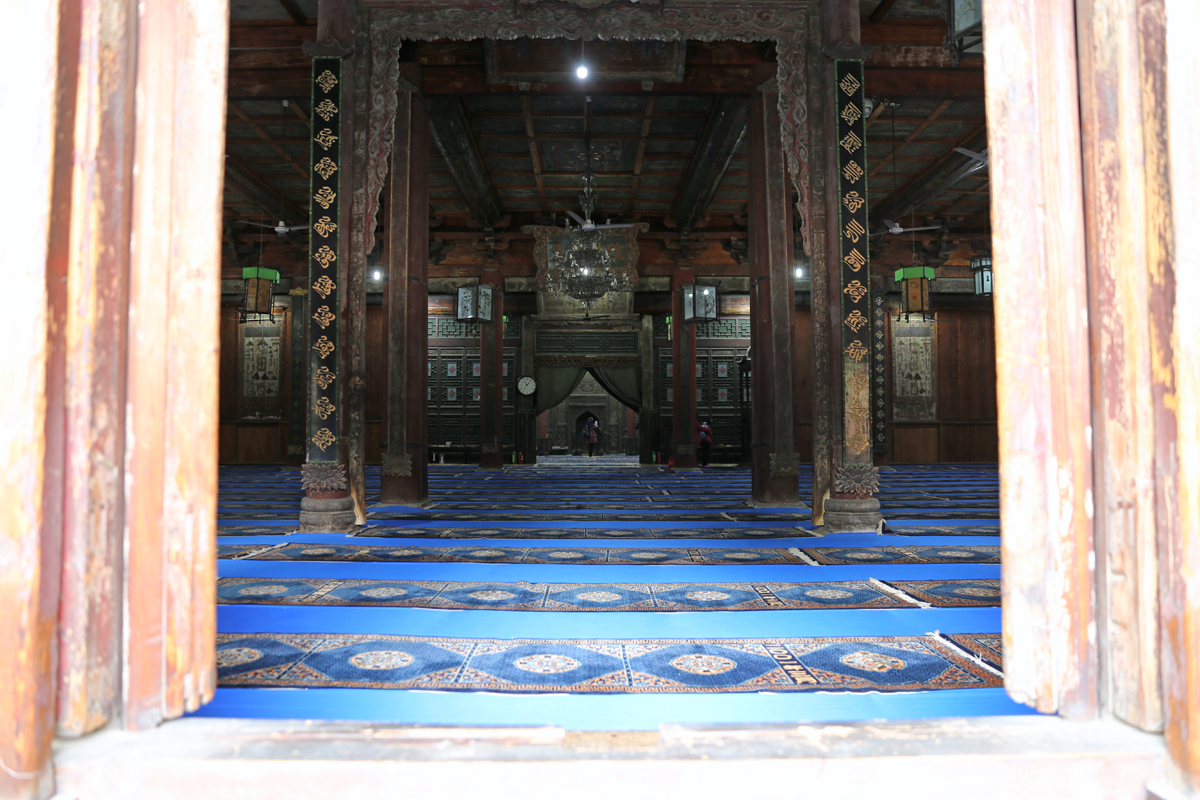

Sprawling across an area of 12,000 square metres (14,352 sq. yd.), the Great Mosque of Xi’an contains over twenty different buildings. Unlike a typical mosque, it is made up of pavilions and pagodas, and is laid out much like a Chinese temple, with successive courtyards following a single axis. The major way in which it differs from a Chinese temple, however, is that its grand axis is aligned from east to west in order to face Mecca, rather than from north to south in accordance with traditional feng shui[1] practices. In-keeping with Islamic tradition, the mosque is richly decorated with geometric and floral motifs, but contains few depictions of living creatures, the only exception being occasional images of dragons. Fabulous works of calligraphy are displayed throughout the complex, some of which are in Chinese, some of which are in Arabic, and a handful of which are in a fusion of styles referred to as “Sini”, which consists of Arabic text written in a traditionally Chinese calligraphic style.

The complex is made up of four successive courtyards that lead up to the main prayer hall, which is backed by a fifth and final courtyard. Each courtyard is lined with lush greenery and contains a signature monument, such as a pavilion, screen, or freestanding gateway. After all, in a complex this expansive, you need something to help you stand out! In the first courtyard, the signature monument comes in the form of an elaborate style of wooden gateway known as a paifang, which is 9 metres (30 ft.) in height and is topped with a brightly coloured glazed-tile roof. This paifang is matched by a similar one in the second courtyard, although this is not its central feature. That honour is reserved for the two stone steles[2] that stand opposite this paifang, which have each been carved by a famous calligrapher. The first was written by Mi Fu of the Song Dynasty (960-1279), while the second was inscribed by Dong Qichang of the Ming Dynasty.

Step through another elegant roofed pavilion and you’ll find yourself in the third courtyard, which is known as the Qing Xiu Dian or “Place of Meditation”. This courtyard is home to the illustrious Xingxin Tower or “Tower of the Visiting Heart”. With a name that romantic, you know it must be something special! This spectacular brick tower is over 10 metres (33 ft.) in height and serves a particularly unique function within the mosque. Traditionally mosques built before the Great Mosque of Xi’an would have a minaret, where the call to prayer would take place, and a separate bangke or “moon watching” pavilion, which was a staple of traditional Chinese temples. The Xingxin Tower, however, was the first of its kind to combine both of these functions, representing another merge between the traditionally Chinese and Islamic features of the mosque.

The fourth courtyard is home to yet another beautiful pavilion, which is known as the Fenghua or “Phoenix” Pavilion. Built during the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912), the pavilion was so named because of its resemblance to a phoenix spreading its wings. Alongside being a beautiful addition to the mosque, the Phoenix Pavilion serves a very special purpose, as it blocks a direct view to the prayer hall at the western end of the courtyard. The prayer hall, which is the main focus of the entire complex, is the only part of the mosque that is not open to the public and is still used today by the local Hui Muslims. Prayer services are held in this hall five times per day and the hall itself can hold upwards of 1,000 people at any given time. Behind the prayer hall, there are two circular moon gates that lead to the fifth courtyard, where two small manmade hills have been constructed for the ceremonial viewing of the new moon.

[1] Feng Shui: This theory is based on the premise that the specific placement of certain buildings or objects will bring good fortune.

[2] Stele: An upright stone slab or pillar that bears an inscription and usually marks a burial site, like a tombstone.

Make your dream trip to The Great Mosque of Xi’an come true on our travel: Explore the Silk Road in China