The Huaqing Hot Springs

The Huaqing Hot Springs are a complex of hot springs located at the northern foot of Mount Li in Shaanxi province, just 30 kilometres (19 mi) east of Xi’an. Thanks to its unusual shape, Mount Li or Mount “Black Horse” supposedly looks like a black horse galloping through the fields. With all of the unexpected popularity that it currently enjoys, you could almost say that Mount Li is the dark horse of the Qin Mountains! Its natural beauty, coupled with the stunning architecture of the hot springs, makes this scenic spot undeniably alluring. However, it’s not just its aesthetic charm that attracts visitors, but also its captivating history.

During the Western Zhou Dynasty (c. 1046–771 BC), King You built the Li Palace at the base of Mount Li. This palace was expanded during the Qin (221-206 BC) and Han (206 BC–220 AD) dynasties, but didn’t reach its full prominence until the Tang Dynasty (618-907). Emperor Xuanzong of Tang spent huge sums of money expanding it, surrounding it with defensive walls and incorporating the nearby hot springs into its bath houses. He then renamed it Huaqing Palace and, over the course of his 44-year reign, would visit it over 36 times. In fact, he spent so long there that it eventually led to a full-scale rebellion!

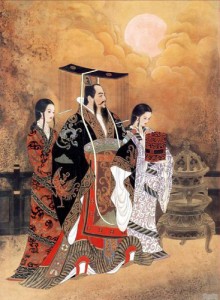

His obsession with the palace began with his consort Yang Guifei [1], who was considered one of the Four Great Beauties of Ancient China and whose appearance was so striking that it supposedly put flowers to shame! Understandably Xuanzong was infatuated with her, so much so that he promoted her cousin, Yang Guozhong, to the position of imperial minister. Eventually Xuanzong began spending so much time at the palace with Consort Yang that he neglected his duties as emperor. Meanwhile, a cunning young general named An Lushan was amassing political power and was able to gain the patronage of the placable Emperor Xuanzong, which eventually led to him obtaining control of a 200,000-strong army. Since he was of Göktürk and Sogdian origin, he maintained amicable relations with several northern ethnic groups and convinced them to join forces with him. This set the foundation for the An Lushan Rebellion.

In 755 AD, An Lushan captured the eastern capital of Luoyang and declared himself Emperor of the short-lived Great Yan Dynasty (756–763). As his forces advanced on the imperial capital of Chang’an (modern-day Xi’an), Xuanzong and the Tang court were forced to flee south. However, his guards believed the Yang family were responsible for An Lushan’s rise to power and assassinated Yang Guozhong. They then demanded that Xuanzong have Yang Guifei put to death. Reluctantly, he ordered his attendant Gao Lishi to strangle her, and this became the basis for Bai Juyi’s renowned poem “The Song of Unending Sorrow”. Although An Lushan was unsuccessful in his claim to power, his rebellion weakened the Tang Empire so greatly that historians believe it was at least partly, if not completely, responsible for the collapse of the dynasty.

Yet it seemed that this wouldn’t be the last rebellion to grace the Huaqing Hot Springs, as the site was also the scene of the infamous Xi’an Incident in 1936. From 1927 through till 1936, China was embroiled in a vicious civil war between the ruling Chinese Nationalist Party (the Kuomintang) and the Chinese Communist Party. The head of the CNP, Chiang Kai-shek, dedicated all of his energy and resources to campaigns against the CCP, in spite of pleas from his colleagues Zhang Xueliang and Yang Hucheng that he focus instead on amassing power to defend against the invading Japanese army.

On December 12th 1936, Chiang Kai-shek was staying at the Huaqing Hot Springs and the warlord Zhang decided to grasp the opportunity. He instructed his army to open fire on the pavilion where Chiang was staying, but Chiang managed to escape through a window and leapt over the back wall. He was captured hours later on Mount Li, and the place where he was found is now marked by an iron chain and a pavilion. After nearly a month of being held hostage and taking part in intense negotiations, Chiang eventually agreed to an alliance with the CPC and the first Chinese Civil War ended. So you see, the Huaqing Hot Springs weren’t just a popular spa retreat, they were also a place of revolution. Maybe there really was something in the water after all!

Since much of the original palace was damaged during the An Lushan Rebellion, many of the structures you see today were either rebuilt during the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912) or after 1949. On first entering the palace’s west gate, you’ll come upon the enchanting Nine Dragon Lake. Lotus flowers float delicately on the lake’s surface and a magnificent white marble statue of Yang Guifei is reflected in its waters. Just don’t stare at her for too long, or you might get branded a Peeping Tom!

Many of the surrounding pavilions were rebuilt in the Tang style, such as the Frost Flying Hall, Yichun Hall, Five Chamber Hall, and the Dragon Marble Boat. The Frost Flying Hall was once the bedroom of Emperor Xuanzong and Yang Guifei, while the Five Chamber Hall was where Chiang Kai-shek stayed before he was captured and was also used by the infamous Empress Dowager Cixi as a refuge when the Eight-Nation Alliance captured Beijing in 1900. Evidently it wasn’t as great a hiding place as they all thought!

Yet no spa would be complete without a few luxury baths. There are a total of six bathing areas within the complex and each one had a different function. For example, the Lotus Pool was exclusively used by the Emperor and was named for its characteristic lotus-shape; the Haitang Pool is shaped like a Chinese crab-apple and was used by the Emperor’s concubines; and the Shangshi Pool was solely for the use of government officials. Nowadays the pools have been drained and cannot be used by visitors, so don’t go wearing your swimsuit under your clothes or you’ll be sorely disappointed!

- Guifei: During the Tang Dynasty (618-907), this was the highest rank that could be bestowed on an imperial consort.

The Great Mosque of Xi’an

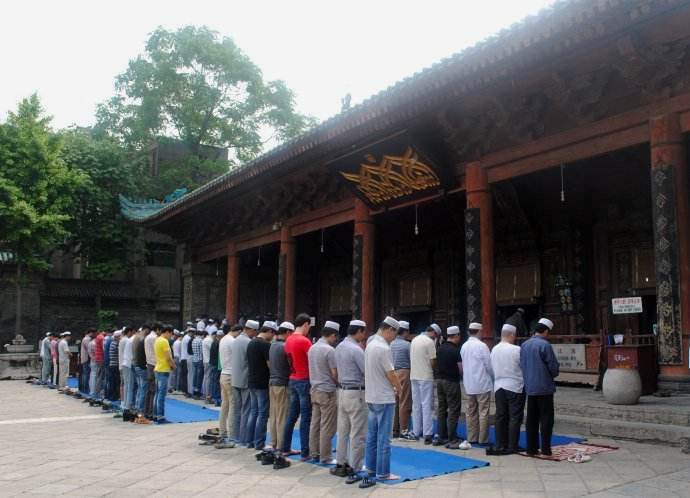

Nestled within the Muslim Quarter in the city of Xi’an, the Great Mosque is the largest of its kind in China and, alongside being a popular tourist site, remains an active place of worship to this day. What makes this mosque particularly unique is that it combines traditional Chinese architectural features with Islamic ones, looking from the outside like a typical Chinese temple but bearing the hallmarks of an Islamic mosque within its interior. According to historical records engraved on a stone tablet within the complex, the original mosque was built on this site in 742 AD, during the Tang Dynasty (618-907). This mosque was built in order to accommodate the many merchants and travellers from Central Asia who settled in Xi’an, the then capital of China, and introduced Islam to the country.

The current mosque, however, was constructed in 1392, during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) and was renovated numerous times thereafter, meaning that many of the structures we find today date back to the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. At the time of its construction, the mosque lay just outside of the Ming Dynasty city walls in a neighbourhood that was designated for foreigners, but today this area has been incorporated into the city proper and can be found close to the city’s famed Drum Tower.

Sprawling across an area of 12,000 square metres (14,352 sq. yd.), the Great Mosque of Xi’an contains over twenty different buildings. Unlike a typical mosque, it is made up of pavilions and pagodas, and is laid out much like a Chinese temple, with successive courtyards following a single axis. The major way in which it differs from a Chinese temple, however, is that its grand axis is aligned from east to west in order to face Mecca, rather than from north to south in accordance with traditional feng shui[1] practices. In-keeping with Islamic tradition, the mosque is richly decorated with geometric and floral motifs, but contains few depictions of living creatures, the only exception being occasional images of dragons. Fabulous works of calligraphy are displayed throughout the complex, some of which are in Chinese, some of which are in Arabic, and a handful of which are in a fusion of styles referred to as “Sini”, which consists of Arabic text written in a traditionally Chinese calligraphic style.

The complex is made up of four successive courtyards that lead up to the main prayer hall, which is backed by a fifth and final courtyard. Each courtyard is lined with lush greenery and contains a signature monument, such as a pavilion, screen, or freestanding gateway. After all, in a complex this expansive, you need something to help you stand out! In the first courtyard, the signature monument comes in the form of an elaborate style of wooden gateway known as a paifang, which is 9 metres (30 ft.) in height and is topped with a brightly coloured glazed-tile roof. This paifang is matched by a similar one in the second courtyard, although this is not its central feature. That honour is reserved for the two stone steles[2] that stand opposite this paifang, which have each been carved by a famous calligrapher. The first was written by Mi Fu of the Song Dynasty (960-1279), while the second was inscribed by Dong Qichang of the Ming Dynasty.

Step through another elegant roofed pavilion and you’ll find yourself in the third courtyard, which is known as the Qing Xiu Dian or “Place of Meditation”. This courtyard is home to the illustrious Xingxin Tower or “Tower of the Visiting Heart”. With a name that romantic, you know it must be something special! This spectacular brick tower is over 10 metres (33 ft.) in height and serves a particularly unique function within the mosque. Traditionally mosques built before the Great Mosque of Xi’an would have a minaret, where the call to prayer would take place, and a separate bangke or “moon watching” pavilion, which was a staple of traditional Chinese temples. The Xingxin Tower, however, was the first of its kind to combine both of these functions, representing another merge between the traditionally Chinese and Islamic features of the mosque.

The fourth courtyard is home to yet another beautiful pavilion, which is known as the Fenghua or “Phoenix” Pavilion. Built during the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912), the pavilion was so named because of its resemblance to a phoenix spreading its wings. Alongside being a beautiful addition to the mosque, the Phoenix Pavilion serves a very special purpose, as it blocks a direct view to the prayer hall at the western end of the courtyard. The prayer hall, which is the main focus of the entire complex, is the only part of the mosque that is not open to the public and is still used today by the local Hui Muslims. Prayer services are held in this hall five times per day and the hall itself can hold upwards of 1,000 people at any given time. Behind the prayer hall, there are two circular moon gates that lead to the fifth courtyard, where two small manmade hills have been constructed for the ceremonial viewing of the new moon.

[1] Feng Shui: This theory is based on the premise that the specific placement of certain buildings or objects will bring good fortune.

[2] Stele: An upright stone slab or pillar that bears an inscription and usually marks a burial site, like a tombstone.

Make your dream trip to The Great Mosque of Xi’an come true on our travel: Explore the Silk Road in China

The Spirituality of the Hui Ethnic Minority

Though the Hui people are not defined by their Islamic faith, the vast majority of them are Muslim. This means they worship at mosques, follow priests known as imams, and worship the holy book called the Quran. Although throughout history many of their mosques have been destroyed due to religious persecution, since 1949 they have been allowed to build them and worship freely.

All Hui communities will surround a mosque and the older mosques tend to be a mixture of Han Chinese and Central Asian architecture, while the newer ones are purely Central Asian in design. One of the finest examples is the Great Mosque in the city of Xi’an, which perfectly amalgamates elements of Chinese and Central Asian architecture.

Some Hui people claim that Islam is the only religion through which Confucianism should be practised and thus accuse Buddhists and Taoists of heresy. However, other Hui people, particularly those who follow the Sunni Gedimu and Yihewani branches of Islam, burn incense during worship, which is thought to be the result of Taoist and Buddhist influences. Many of the other Islamic ethnic minorities, such as the Salar, regard this as a heathen ritual and denounce it.

The Hui are the only Muslims in the world who are known to have female imams and, while male imams as known as ahung, female imams are known as nu ahung. They guide other women in prayer but are not allowed to lead prayers like regular imams.

Qin Shi Huang

Qin Shi Huang (259-210 B.C.) is a figure who’s met in China with both reverence and disgust. He was the First Emperor of China and the first man to single-handedly unify the country, but he was also a tyrant whose dictatorial reign had him reviled for centuries after his death. He masterminded the construction of the Terracotta Army and ordered the construction of what would eventually be the Great Wall. However, his all-consuming greed decimated the country’s resources and it is thought that, under his reign, the population of China more than halved in size. He was so despised by his own people that he was the target of several unsuccessful assassination attempts, one of which was the inspiration for the martial arts epic Hero starring Jet-Li. Qin Shi Huang’s rise to power and his dynasty, though bloody and brutal, has undoubtedly become the stuff of legends.

Early Life

There is much controversy surrounding Qin Shi Huang’s birth. He was born in 259 B.C. in the city of Handan and was given the name Ying Zheng. He was the eldest son of the Qin prince Yiren. His mother was the Lady of Zhao, Yiren’s beloved concubine.

There is much controversy surrounding Qin Shi Huang’s birth. He was born in 259 B.C. in the city of Handan and was given the name Ying Zheng. He was the eldest son of the Qin prince Yiren. His mother was the Lady of Zhao, Yiren’s beloved concubine.

Before Ying Zheng’s birth, his father Yiren was supposedly being held hostage by the State of Zhao and was liberated by a wealthy merchant named Lü Buwei. Yiren then ascended the throne as King Zhuangxiang of Qin. According to historian Sima Qian[1], Lü Buwei introduced Yiren to Ying Zhen’s mother, Zhao Ji. However, unbeknownst to Yiren, Zhao Ji had been Lü Buwei’s concubine for some time and was pregnant with his child. It was rumoured that Ying Zheng was in fact the illegitimate son of Lü Buwei. Ying Zheng’s potential illegitimacy was widely believed throughout China at the time and contributed to the negative view that many people had of him. Modern analysis suggests that Sima Qian probably added this rumour to his records to slander Ying Zheng as, according to Confucian principles, merchants like Lü Buwei were among the lowest of the social classes.

King of Qin

After his father’s death in 246 B.C., Ying Zheng ascended the throne at the age of 13. In light of Ying Zheng’s inexperience, Lü Buwei was appointed as regent prime minister. Lü Buwei was worried that, if he continued as prime minister, Ying Zheng would eventually find out about his affair with Zhao Ji, so he made Lao Ai prime minister instead. However, when an attempt by Lao Ai to overthrow Ying Zheng failed, he was executed. Lü Buwei’s involvement in this coup led to his exile and in 235 B.C. he committed suicide. It was then, at the age of 22, that Ying Zheng took complete control of the State of Qin.

Ying Zheng became King of Qin during what is known as the Warring States Period (r. 475-221 B.C.), which followed the Spring and Autumn Period (r. 770-476 B.C.) of the Zhou Dynasty. During the Zhou Dynasty, dukes were appointed to rule over separate fiefdoms. As the Zhou Dynasty began to collapse, these fiefdoms began to develop into separate states. When the Zhou Dynasty finally fell, these former dukes took control of their respective states and each claimed to be the rightful King. This was a period of great political unrest as the Seven Warring States were constantly at war with one another in a desperate bid to try and expand their empires. Only these major seven states survived as the smaller states, lacking the protection of a centralized government, were swiftly annexed. After seizing control of Qin, Ying Zheng began a military campaign to conquer the six other Warring States.

Unification of China

The State of Qin was shielded by mountains, which provided a natural barrier and made it difficult to invade. This gave Ying Zheng a military advantage. Behind these mountains, Ying Zheng built up a large and powerful army. Between 230 B.C. and 222 B.C., Ying Zheng conquered the States of Han, Zhao, Yan, Wei, and Chu. Finally, in 221 B.C., he annexed the State of Qi and completed his domination of the Warring States. For the first time in history, China was unified under one ruler.

The State of Qin was shielded by mountains, which provided a natural barrier and made it difficult to invade. This gave Ying Zheng a military advantage. Behind these mountains, Ying Zheng built up a large and powerful army. Between 230 B.C. and 222 B.C., Ying Zheng conquered the States of Han, Zhao, Yan, Wei, and Chu. Finally, in 221 B.C., he annexed the State of Qi and completed his domination of the Warring States. For the first time in history, China was unified under one ruler.

Ying Zheng gave himself the regnal name Shi Huangdi. He believed he was greater than the divine Three Sovereigns (Sān Huáng) and the legendary Five Emperors (Wŭ Dì) of Chinese prehistory, so combined their names to create the title Huangdi or “Emperor”. The “Shi” part of his regnal name indicates that he was the first, so his title can be translated to mean “First Emperor”. His intention was that his successors should be named “Second Emperor”, “Third Emperor” and so on. He is now commonly referred to as Qin Shi Huangdi to differentiate him from emperors of other dynasties.

The Qin Dynasty (221-206 B.C.)

Qin Shi Huang was responsible for unifying China in more ways than just conquering the Warring States. He centralized the government by abolishing the rulers of the previous States and placing the whole country under his rule. He changed the imperial system so that official appointments were based on merit rather than on hereditary right, meaning he chose his own officials.

With the help of his chancellor, Li Si, Qin Shi Huang standardized Chinese units of measurement, such as weights and measures, and also units of currency. He created a standardised currency known as the Ban liang coin, a circular coin that has a square hole in the middle. He created an extensive network of roads and canals that helped link all regions of his empire, enabling people to trade much more easily. These measures helped to unify the country economically. Perhaps his most significant achievement was his regularisation of Chinese script. Under the guidance of Li Si, the seal script of the State of Qin became the standard script for the whole country. This was the first time in history that there had been one language and one system of communication across the whole country.

Yet, even after he had unified China, he was still the target of several assassination attempts, including one in 218 B.C. when he was traveling through the mountains and an unidentified strongman supposedly threw a colossal, metal cone, weighing approximately 97 kilograms (160 lbs.), at his carriage. The vitriol levelled against him was in part due to the many pitfalls of his reign. He banned all other schools of thought besides legalism and eliminated the Hundred Schools of Thought, which included Confucianism and older forms of Buddhism. The ideology behind legalism was that people should obey the laws or be punished accordingly, making it a strict and ruthless philosophy of governance.

Yet, even after he had unified China, he was still the target of several assassination attempts, including one in 218 B.C. when he was traveling through the mountains and an unidentified strongman supposedly threw a colossal, metal cone, weighing approximately 97 kilograms (160 lbs.), at his carriage. The vitriol levelled against him was in part due to the many pitfalls of his reign. He banned all other schools of thought besides legalism and eliminated the Hundred Schools of Thought, which included Confucianism and older forms of Buddhism. The ideology behind legalism was that people should obey the laws or be punished accordingly, making it a strict and ruthless philosophy of governance.

In accordance with his attempt to quash these schools of thought, on the advice of Li Si, Qin Shi Huang had almost all of the books written before his Dynasty burned. He spared only books on astrology, agriculture, medicine, divination, and the history of the State of Qin. According to Sima Qian, he also had 460 scholars buried alive, although modern analysis suggests that this was a fabrication used by Confucian scholars to distance themselves from the failed dynasty.

In terms of his architectural achievements, the construction of the Great Wall is often attributed to him. During his reign, in order to protect the northern frontier from the Xiongu people, he masterminded the building of a huge wall to the north that connected the existing state walls and incorporated mountains and cliffs as defensive structures. This was the precursor of the Great Wall. He also built the Lingqu Canal, which was intended to transport supplies to his army. This massive canal is 34 kilometres in length and links the Xiang River and Li River, connecting North China with South China. The Lingqu is considered one of the three great feats of Ancient Chinese engineering, along with the Great Wall and the Sichuan Dujiangyan Irrigation System. However, his greatest legacy is arguably his mausoleum. It contains the Terracotta Army, an army formed of over 6,000 clay figures. Each figure is unique and was based on a real soldier in Qin Shi Huang’s army. His tomb remains unopened to this day.

Qin Shi Huang was notoriously superstitious and was obsessed with trying to find the elixir of life. In his lifetime, he visited Zhifu Island three times in the hopes of finding the Mountain of Immortality (Penglai Mountain). Yet his quest for immortality would eventually prove his undoing. In 211 B.C., Qin Shi Huang was plagued by a dark omen, a meteor that landed in Dongjun. Someone supposedly carved the words “The First Emperor will die and his land will be divided” into the meteor. Qin Shi Huang had all of the people in the vicinity executed and had the meteor burned and pulverized.

A year later, the Emperor died at his palace in Shangqiu prefecture. His death was caused by ingesting mercury pills, which ironically had been prescribed to him by alchemists to make him immortal. He was succeeded by his son, Huhai, but Huhai was not as capable a ruler as his father. Revolts soon broke out across the country and, only four years after the First Emperor’s death, the Qin Dynasty collapsed. Perhaps the meteor’s prophecy was true and Qin Shi Huang was right to have been so superstitious after all.

[1] Sima Qian (145–90 BCE): A Chinese historian whose most noted work was called Shiji or Records of the Grand Historian

Qianling Mausoleum

The Qianling Mausoleum is unique in that the main tomb has not been looted by grave robbers nor has it been excavated, meaning it has remained sealed and untouched for over 1,300 years. Thus, of the 18 Tang Dynasty Mausoleums, the Qianling Mausoleum is considered to be the most well-preserved. The main tomb houses one of China’s most controversial royal figures, Empress Wu Zetian, who was the only woman to have ever formally ruled China. She is also the only Empress to have been buried alongside her husband, the Emperor. The tomb itself follows the same structural pattern as Zhaoling Mausoleum in that it has been built into the side of a mountain. Only members of the imperial family were allowed to build their mausoleums into natural mountains and, of the 18 Tang Dynasty emperors, 14 of them chose to have mountains serve as their burial mounds. Though in scale Qianling Mausoleum may not be as impressive as the colossal Zhaoling Mausoleum, in terms of artistic beauty it is unmatched. Littered throughout the mausoleum you’ll find statues, murals and painted pottery, all a tableau of ancient China frozen in time. From the haunting stone funeral procession that leads to the Emperors tomb to the underground tombs of Princes and Princesses that have now been opened to the public, the Qianling Mausoleum takes you back to a time when men were gods and built monuments so as to be remembered for time immemorial.

Qianling Mausoleum is located on Mount Liang, about 80 kilometres (50 miles) northwest of Xi’an, and was built in 684 A.D., a year after Emperor Gaozong suffered the debilitating stroke that killed him. With the Leopard Valley to the east and the Sand Canyon to the west, the Mausoleum on Mount Liang is the perfect scenic spot to enjoy the diversity of landscapes in China. On the surface of the Mausoleum there were once 378 magnificent buildings, including the Sacrificial Hall, the Pavilion, and the Hall of Ministers. Sadly these surface buildings have all but disappeared, leaving only their underground counterparts. Aside from these surface buildings, which were relatively common among Tang Emperor’s tombs, Qianling Mausoleum has several features that make it unique among the other mausoleums. The burial mounds on the southern peak of Mount Liang each have towers erected at the centre of each mound and are thus named “Naitoushan” or “Nipple Hills” due to their resemblance to breasts. These Nipple Hills form a sort of gateway into the Mausoleum, creating a visual effect that is both stunning and exclusive to Qianling Mausoleum. The main imperial tomb, however, is located on the northern peak. There you’ll find the tallest burial mound and a 61 metre (200 ft.) long, 4 metre (13 ft.) wide tunnel carved out of the mountain that leads into the inner tomb chambers. This is the final resting place of Emperor Gaozong and Empress Wu Zetian, which has remained unopened to this day.

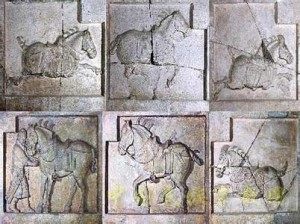

The most magnificent and otherworldly feature of Qianlong Mausoleum are the stone statues that have braved the elements and remained suspended in time for over a thousand years. If you follow the Spirit Way that leads to the Emperor’s tomb, you will undoubtedly discover the 124 stone statues that serve as his funeral procession. These include statues of horses, winged horses, horses with grooms, lions, officials, foreign envoys and, most bizarre of all, ostriches. The first ostrich was presented to the Tang court by a khan of the Western Turks in 620 A.D. and the Tushara Kingdom sent another one in 650 A.D. It is believed that early Chinese representations of phoenixes were based on these ostriches. The ostriches at Qianling Mausoleum serve as a symbol of the Tang Dynasty’s power and influence over its foreign neighbours.

The most magnificent and otherworldly feature of Qianlong Mausoleum are the stone statues that have braved the elements and remained suspended in time for over a thousand years. If you follow the Spirit Way that leads to the Emperor’s tomb, you will undoubtedly discover the 124 stone statues that serve as his funeral procession. These include statues of horses, winged horses, horses with grooms, lions, officials, foreign envoys and, most bizarre of all, ostriches. The first ostrich was presented to the Tang court by a khan of the Western Turks in 620 A.D. and the Tushara Kingdom sent another one in 650 A.D. It is believed that early Chinese representations of phoenixes were based on these ostriches. The ostriches at Qianling Mausoleum serve as a symbol of the Tang Dynasty’s power and influence over its foreign neighbours.

Similarly, the sixty-one stone envoys that perpetually mourn Emperor Gaozong’s death were directly commissioned by Empress Wu Zetian and designed after the sixty-one foreign envoys that were physically present at Emperor Gaozong’s funeral. Each figure is wearing a long robe with a wide belt and boots and, if you look closely, you’ll find the name of each individual and the country he represented carved on his back. These foreign envoys were constructed to further symbolise the Tang Dynasty’s far reaching influence and powerful empire. Tragically, for reasons unknown, these sixty-one statues have been decapitated.

Surrounding the main tomb, archaeologists have also recovered four gates, parts of the inner wall, and parts of the outer wall that guarded the tomb, along with remnants of houses that once belonged to workers charged with maintaining the tomb. The four gates are called Zhu Que Men (Rosefinch Gate) to the south, Xuan Wu Men (Mystical Power Gate) to the north, Qing Long Men (Black Dragon Gate) to the east, and Bai Hu Men (White Tiger Gate) to the west. Near the main tomb you’ll also find the magnificent Qijie Bei or “Tablet of the Seven Elements”, which is so called because it symbolises the Sun, Moon, Metal, Wood, Water, Earth and Fire, the seven elements in ancient Chinese philosophy. This tablet carries an inscription describing the achievements of the Emperor, which was composed by the Empress Wu Zetian and written in the calligraphic style of Emperor Zhongzong (Emperor Gaozong’s son). Interestingly, near the Tablet of the Seven Elements, there sits the Blank Tablet, which has dragons and oysters carved upon it but no inscription. It is the only blank tablet to be found in any royal mausoleum in China and was erected by Empress Wu Zetian, who stated in her will: “My achievements and errors must be evaluated by later generations, therefore carve no characters on my stele[1]”. This may seem like an odd thing for anyone to say, particularly from the only woman to have ever ruled as Emperor, and it shines a light directly on the controversy surrounding Wu Zetian.

Although the Emperor’s tomb has not been excavated, the tombs of Crown Prince Zhanghuai, Prince Yide and Princess Yongtai have all been unearthed and opened to the public. The one thing these three royal figures had in common was that they were all put to death by their mother and grandmother respectively, Wu Zetian, when they were still young. These three unfortunate youths, who suffered tragic deaths, were not even honored with imperial tombs until Empress Wu Zetian finally died in 706 A.D and their brother and father respectively, Emperor Zhongzong, was finally allowed to give his brother and children a proper burial. Wu Zetian was not only implicated in the deaths of these three relatives but also in the deaths of two of her other children and several other family members, friends and officials that either displeased her or threatened her claim to the throne. Thus you can understand why, in light of all these nefarious deeds, Wu Zetian’s tombstone has remained blank for over a thousand years. Though Wu Zetian’s reign of tyranny has long ended, her exploits have not been forgotten.

Although the Emperor’s tomb has not been excavated, the tombs of Crown Prince Zhanghuai, Prince Yide and Princess Yongtai have all been unearthed and opened to the public. The one thing these three royal figures had in common was that they were all put to death by their mother and grandmother respectively, Wu Zetian, when they were still young. These three unfortunate youths, who suffered tragic deaths, were not even honored with imperial tombs until Empress Wu Zetian finally died in 706 A.D and their brother and father respectively, Emperor Zhongzong, was finally allowed to give his brother and children a proper burial. Wu Zetian was not only implicated in the deaths of these three relatives but also in the deaths of two of her other children and several other family members, friends and officials that either displeased her or threatened her claim to the throne. Thus you can understand why, in light of all these nefarious deeds, Wu Zetian’s tombstone has remained blank for over a thousand years. Though Wu Zetian’s reign of tyranny has long ended, her exploits have not been forgotten.

If you visit the tombs today, you’ll find a much more positive representation of ancient China. The three tombs that have been opened up to the public are covered in stunning murals of typical scenes in the Imperial Court, including beautiful maidservants, nobles playing Polo on horseback and royals receiving their foreign guests. Though these paintings have been worn by time, the exuberant colours and vivid facial expressions of the characters within them still evoke a real sense of how extravagant life must have been during the Tang Dynasty. Princess Yongtai’s tomb has been converted into a museum, where you’ll find a collection of the 4,300 historical relics that were exhumed from the three tombs. From the delicately carved jade funeral eulogiums to the painted figures of riders with their horses gilt faced, inlaid lavishly with gold, we’re sure you’ll find a trip to Qianlong Museum and Qianlong Mausoleum both rewarding and fascinating. From the outset, it is truly a feast for the eyes.

[1] Stele: An upright stone slab or pillar that bears an inscription and usually marks a burial site, like a tombstone.

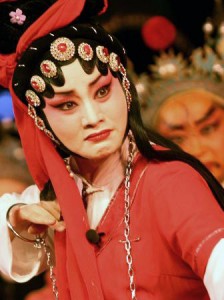

Qinqiang Opera

Qinqiang opera is widely considered to be the forefather of all styles of Chinese opera. In ancient times, it was originally just called Qin opera and nowadays it is also known as Luantan opera, meaning “random pluck” or “strumming” opera. The name “Qin” derives from the fact that Qinqiang opera dates all the way back to the Qin Dynasty (221-206 B.C.) and its heritage stretches back over 2,500 years, making it one of the oldest forms of opera in China. This style of opera first originated from the folk songs of Shaanxi province and Gansu province, and eventually made its way to Beijing, where it heavily influenced the incredibly popular Peking opera.

As a style, it was refined during the Han Dynasty (206 B.C. – 220 A.D.), flourished during the Tang Dynasty (618-907), and was officially acknowledged as a style of opera by the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368). It went through a secondary period of refinement and maturation during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) and, by the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), it had spread throughout China. During the reign of Emperor Qianlong (1736-1795), there were over 36 Qinqiang troupes in the city of Xi’an alone. Supposedly Qinqiang opera started in the fields and farms of the northwestern provinces, when locals would shout to one another from across the fields. Eventually these locals developed a system of shouted songs to communicate with one another and this is where Qinqiang derives its distinctive “shouted out” style of singing. Thanks to this unusual singing style, Qinqiang opera is considered one of the “ten strange wonders of Shaanxi province”.

Along with this shouted style of singing, Qinqiang opera also incorporates bangzi[1] melodies. These are one of China’s Four Great Characteristic Melodies and Qinqiang is one of the most significant styles of Bangzi opera around today. The opera will usually be accompanied by several instruments, the most important of which is the banhu[2]. The banhu is either strummed or plucked, which is what earned this style of opera the name Luantan or “Random Pluck” opera. The characteristic arias of Qinqiang opera are deep, loud, piercing and bold, with singing of an impressively high pitch. There are two main types of arias in this style of opera: huanyin (joyous tunes) and kunyin (sad tunes). Though the huanyin are magnificent, the kunyin are widely considered to be the most hauntingly beautiful.

Along with this shouted style of singing, Qinqiang opera also incorporates bangzi[1] melodies. These are one of China’s Four Great Characteristic Melodies and Qinqiang is one of the most significant styles of Bangzi opera around today. The opera will usually be accompanied by several instruments, the most important of which is the banhu[2]. The banhu is either strummed or plucked, which is what earned this style of opera the name Luantan or “Random Pluck” opera. The characteristic arias of Qinqiang opera are deep, loud, piercing and bold, with singing of an impressively high pitch. There are two main types of arias in this style of opera: huanyin (joyous tunes) and kunyin (sad tunes). Though the huanyin are magnificent, the kunyin are widely considered to be the most hauntingly beautiful.

Qinqiang was one of the earliest forms of opera to focus on the expression of human emotion. Its use of exaggerated, stylised movements and facial expressions to imply actions, emotions, and events has been replicated in numerous other successive styles of opera. Most Qinqiang operas depict stories of ancient wars of resistance against foreign invaders, battles between good and evil, and the struggle against feudal oppression. They were designed to reflect the honesty, bravery and diligence of the common people of Northwest China.

There are 13 character types in Qinqiang opera. These include four kinds of sheng or male characters, six kinds of dan or female characters, two kinds of jing or painted face characters, and one kind of chou or clown character. There are four major genres of Qinqiang opera, and this is predominantly due to the different dialects and folk music in the areas in which they were developed. Qinqiang is not just about the singing; it is a complete performance art and incorporates dancing, acrobatics and martial arts into every performance. Perhaps the most famous characteristic of Qinqiang is its style of fire-breathing, which has been copied in other successive styles of opera. Watching a performer in traditional dress breathe fire across the stage is a truly enthralling spectacle. The “hat dance” is another unique performance skill of Qinqiang opera, where performers will make a hat or object appear to dance on their head. Originally there were upwards of 10,000 Qinqiang works that were widely popular throughout China, of which only 4,700 remain. The Ghost’s Hate, Down the East River (下河东), The Golden Qilin or The Golden Unicorn (金麒麟), and The Port of Jiujiang (九江口) are just a handful of examples.

Unfortunately, since the 1980s the declining popularity of Chinese opera means that the tradition of Qinqiang opera has gradually started to disappear. However, many opera performers, opera enthusiasts, and government officials are committed to the preservation of this fine cultural art. In 2006 it was listed as a National Intangible World Heritage by the Chinese government and since then measures, such as government stipends for Qinqiang opera troupes and free tuition for anyone choosing to train in Qinqiang opera, have helped bolster the prevalence and popularity of this style of opera. There is now even a Qinqiang Opera Museum in Lanzhou, Gansu.

[1] Bangzi: A Chinese woodblock percussion instrument. Traditionally, two bangzi were used to keep the main tune during an opera, like a primitive form of metronome. Now the term bangzi or bangziqiang is widely used to refer to a type of melody used in Chinese opera.

[2] Banhu: A Chinese bowed stringed instrument. The soundbox is traditionally made from a coconut shell and the rest is made from wood. They have two strings.

Mount Hua

According to legend, the Queen Mother of the West was holding her Flat Peach Carnival when she accidentally spilled some of her jade wine down from paradise, which caused a colossal flood here on earth. The flood destroyed all of the villages in the Huashan area so the deity Shaohao informed the Jade Emperor of the disaster. The Jade Emperor promptly sent the deity Juling to earth to stem the flood. As Juling descended from the clouds he rested his left hand on one side of the peak and his right leg on the other, which ripped the mountain into two halves and allowed the floodwater to rush out. His handprint supposedly remains on the Immortal’s Palm Peak, which sits high up on Mount Hua.

Standing at an impressive 2,100 metres (7,070 ft.) at its highest peak, it is no wonder that Mount Hua is listed as one of the Five Great Mountains of China. It is located approximately 120 kilometres east of Xi’an, near a city called Huayin. It sits at the eastern end of the Qin Mountains and is made up of five peaks. Although the mountain is undoubtedly a phenomenal natural specimen, it is more well-known in China for its spiritual and religious significance. Each of its five peaks has an intricately woven folktale behind it, which is intertwined with the Chinese mythology that is now known to be part legend and part historical fact. To the locals and to the average visitor, Mount Hua has an unmistakably mystical feel about it. If you’re looking for somewhere where you can embrace your spirituality and discover more about the fascinating schools of thought behind Chinese philosophy, then a trip to Mount Hua is a must.

The five main peaks of the mountain are simply named East Peak, South Peak, West Peak, Central Peak, and North Peak, with South Peak being the highest and North Peak being the lowest.

Every peak has inherited a second name according to its features or the legendary stories behind it.

Central Peak is known as Jade Maiden Peak. The story behind its name is a perfect example of how Chinese legend has become inseparably intertwined with history. There is a Taoist Temple at the top of this peak called the Jade Maiden Temple. Legend has it that the daughter of Duke Mu of Qin[1] (569 – 621 BC) loved a man who was talented at playing the tung-hsiao[2]. In order to avoid this temptation and cultivate her spirituality, she gave up the royal life she had become accustomed to and became a hermit, secreting herself on the Central Peak of Mount Hua. From then on, the temple was established and the peak was named Jade Maiden Peak after the Duke’s daughter. Near to the Jade Maiden Temple you will also find the Rootless Tree and the Sacrificing Tree, which also have mystical stories behind them that add to the ethereal feel of Central Peak.

Unfortunately not every story behind each peak is quite so magical. The South Peak is called Landing Wild Geese Peak simply because, according to legend, geese returning from the south often landed on this peak. It is home to the beautiful Black Dragon Pool and the Baidi Temple or Jintian Palace, a Taoist Temple that is nationally considered the host temple of the deity Shaohao. South Peak is also the site of the infamous Plank Road, a plank path built along the side of a vertical cliff that is only about 0.3 metres (about 1 foot) wide and forces the intrepid hiker to look down at the almost bottomless gulf below them. Although there is a chain running along the cliff-face that hikers can clip themselves on to, the experience of creeping along the narrow path and having to constantly hook and unhook yourself from your only safety net, so to speak, is only for the bravest of travellers.

Like South Peak, North Peak is rather simply named Cloud Terrace Peak because the clouds that accumulate around the peak look like a flat terrace. It looks so uncanny that you might get the impression you could almost step out onto the clouds. On one side of the peak is the Ear-Touching Cliff, which is so narrow that you supposedly have to press your ear to the cliff-face to climb it. Although this may seem like a joke, it is important to note that some of the paths on Mount Hua, such as the infamous Plank Road, are notoriously treacherous. The government has tried to put in as many safety measures as it can to make them safer but it is advised that you take the risks into careful consideration before venturing out onto the more dangerous paths. Historically there have been fatalities on these paths when visitors have not been careful or not heeded the warnings.

The West Peak is called the Lotus Flower Peak because there is a Taoist Temple there called Cuiyun Palace which has a huge rock in front of it that looks like a lotus flower. There are seven other rocks by Cuiyun Palace that are supposedly the site where the legendary hero Chenxiang ripped the mountain apart to save his mother, the Heavenly Goddess San Sheng Mu, in the folktale “The Magic Lotus Lantern”.

The East Peak, also known as Facing Sun Peak, is the best place to watch the sunrise and takes approximately 4 to 6 hours to climb. It is home to the famous Immortal’s Palm Peak mentioned earlier. Immortal Palm’s Peak is ranked as one of the Eight Scenic Wonders of the Guanzhong Area and is so-called because of the natural rock veins on the cliff, which look like a giant handprint and were supposedly caused by the deity Juling when he fell from heaven.

The East Peak, also known as Facing Sun Peak, is the best place to watch the sunrise and takes approximately 4 to 6 hours to climb. It is home to the famous Immortal’s Palm Peak mentioned earlier. Immortal Palm’s Peak is ranked as one of the Eight Scenic Wonders of the Guanzhong Area and is so-called because of the natural rock veins on the cliff, which look like a giant handprint and were supposedly caused by the deity Juling when he fell from heaven.

As early as the 2nd century B.C., it was recorded that a Taoist temple named the Shrine of the Western Peak rested at the base of the mountain. Taoists believed that the god of the underworld lived inside the mountain and this temple was used primarily by spirit mediums to contact this god and his underlings. Unlike Mount Taishan, which attracted many pilgrims, Mount Hua only seemed to attract Imperial pilgrims or local pilgrims due to its relative inaccessibility. Historically this earned it the reputation of being a retreat only for the hardiest of hermits, regardless of what religion they followed, as only those who were particularly strong-willed or spiritually enlightened could master the treacherous climb. Nowadays there are a number of temples and religious structures littered throughout the mountain, including a Taoist temple atop the Southern Peak that has been converted into a teahouse. At the foot of the mountain you’ll also find Xinyue Temple and the Jade Spring Temple. The sheer number of temples and religious constructions on and around the mountain demonstrate just how spiritually significant it is.

With all of the myths, history and spirituality behind it, Mount Hua has truly lived up to its reputation as one of the Five Great Mountains of China. When climbing the mountain and visiting the many temples on its peaks, you’re guaranteed not only beautiful scenic views but also a sense of spiritual calmness.

Xinyue Temple

Xinyue Temple rests at the bottom of Mount Hua. It was built to honour the god that is believed to live inside the mountain and was constructed during the reign of Emperor Wudi of the Western Han Dynasty (206 B.C. – 24 A.D.). Its stunning appearance and monumental size have earned it the name “The Forbidden City of Shaanxi Province”. Important scenic spots in Xinyue Temple include Haoling Gate, Five-Phoenix Pavilion, Lingxing Gate, Golden City Gate, Haoling Palace, the Emperor’s Study, and Longevity Pavilion. In the Five-Phoenix Pavilion there is a place called the Small Steles Forest where there are many impressive steles[3], including one of the most famous steles in the world: the Huashan Monument.

Xinyue Temple rests at the bottom of Mount Hua. It was built to honour the god that is believed to live inside the mountain and was constructed during the reign of Emperor Wudi of the Western Han Dynasty (206 B.C. – 24 A.D.). Its stunning appearance and monumental size have earned it the name “The Forbidden City of Shaanxi Province”. Important scenic spots in Xinyue Temple include Haoling Gate, Five-Phoenix Pavilion, Lingxing Gate, Golden City Gate, Haoling Palace, the Emperor’s Study, and Longevity Pavilion. In the Five-Phoenix Pavilion there is a place called the Small Steles Forest where there are many impressive steles[3], including one of the most famous steles in the world: the Huashan Monument.

The Jade Spring Temple (Yuquan Temple)

The Jade Spring Temple is a Taoist temple that rests at the foot of Mount Hua. Its main function is to hold Taoist activities and to allow its monks to practice Taoism. It was built by Jia Desheng during the Northern Song Dynasty (960 – 1127) to honour his teacher Chen Tuan[4] (871 – 989). Its name originates from a charming tale about a girl named the Golden Fairy Princess. Supposedly the Golden Fairy Princess was washing her hair beside the Jade Well on Mount Hua when she accidentally dropped her beautiful jade hair clasp into the well. She searched far and wide for her precious hair clasp but to no avail. Miraculously, as she was washing her hands with the spring water at the temple, she found her lost jade hair clasp. Since this spring was connected to the Jade Well, the princess decided to name the temple the Jade Spring Temple. Important scenic spots at this temple include the Long Corridor of Seventy-two Windows, which is a unique construction among Taoist temples across China.

[1] Duke Mu of Qin: He was the fourteenth ruler of the Zhou Dynasty State of Qin.

[2] Tsung-hsiao: A kind of Chinese flute that is held vertically rather than horizontally.

[3] Stele: An upright stone slab or pillar that bears an inscription and usually marks a burial site, like a tombstone.

[4] Chen Tuan: He was a famous scholar and hermit of the Quanzhen branch of Taoism. He helped to combine elements of Quietism, Taoism, Confucianism and Buddhism, which greatly aided the development of neo-Confucianism.

Join our travel to challenge the Mount Hua: Explore the Silk Road in China and Explore Chinese Culture through the Ages

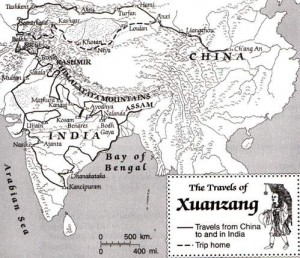

Xuanzang

The works of Xuanzang (602 – 664) have provided invaluable insight into ancient civilizations and have been used by historians, geographers, philosophers, and archaeologists across the globe. Xuanzang was a monk, traveller, writer, historian, and translator, and somehow managed to succeed in every venture he put his mind to. His 16 year pilgrimage to India allowed him to collect hundreds of priceless artefacts, which he brought back to China to further the study of Buddhism. If it was not for his tireless efforts, many of the Buddhist texts and much of the information about ancient civilizations that we have today would have been lost.

Early Life

Xuanzang was born around about 602 A.D., in Goushi Town, Luozhou (near modern-day Luoyang, Henan), and was given the name Chen Hui. He was the youngest of four children and came from a long line of prestigious academics. His great-grandfather, Chen Qin, had served as the Prefect of Shangdang (modern-day Changzhi, Shanxi). His grandfather, Chen Kang, had been a professor at Taixue (the Imperial Academy). And his father, Chen Hui, was a conservative Confucian who served as the magistrate of Jiangling County during the Sui Dynasty.

Like his siblings, from an early age Xuanzang was educated by his father, who introduced him to the principles of Confucianism. He began observing Confucian rituals at the age of eight. Many of his family members were impressed with his early development and genius-level intellect.

Conversion to Buddhism

Although Xuanzang’s household was essentially Confucian, his older brother Chen Su was a Buddhist monk. Xuanzang expressed great interest in Buddhism and, when his father died in 611, he made the decision to live in Jingtu Monastery with his brother. He studied there for five years and, at the age of thirteen, he was ordained as a śrāmaṇera (novice monk).

In 618, both Xuanzang and his brother fled to Chang’an (modern-day Xi’an) to escape the unrest caused by the fall of the Sui Dynasty, and made their way to Chengdu, Sichuan, where they studied in Kong Hui Monastery. It was in this monastery that Xuanzang was ordained as a bhikṣu (full monk) at the age of twenty. In 622 he returned to Chang’an to study foreign languages and, in 626, he began learning Sanskrit. He chose to do this mainly because he was confused by the discrepancies in the Buddhist texts he had read and wanted to learn to translate the originals himself.

Pilgrimage

While studying in Chang’an, Xuanzang supposedly had a dream that indicated he should travel to India. It was this, coupled with his belief that the Buddhist texts available in China were insufficient, that convinced him to start his pilgrimage. However, at that time Emperor Taizong had prohibited foreign travel because of China’s war with the Göktürks[1], so in 629 Xuanzang slipped through the Yumen Pass under cover of darkness and made the dangerous journey across the Gobi Desert.

He eventually arrived in Liangzhou (modern-day Gansu province), which was the starting-point of the Silk Road trade route that connected China with Central Asia. He spent approximately a month preaching in Liangzhou before he was invited to Hami (modern-day Hami City, Xinjiang) by King Qu Wentai, who was a pious Buddhist of Chinese descent. However, it soon became apparent to Xuanzang that King Qu Wentai had ulterior motives. He planned to detain Xuanzang and make him the ecclesiastical head of his Court. Xuanzang went on a hunger strike until the King relented and allowed him to leave.

He eventually arrived in Liangzhou (modern-day Gansu province), which was the starting-point of the Silk Road trade route that connected China with Central Asia. He spent approximately a month preaching in Liangzhou before he was invited to Hami (modern-day Hami City, Xinjiang) by King Qu Wentai, who was a pious Buddhist of Chinese descent. However, it soon became apparent to Xuanzang that King Qu Wentai had ulterior motives. He planned to detain Xuanzang and make him the ecclesiastical head of his Court. Xuanzang went on a hunger strike until the King relented and allowed him to leave.

As a show of good faith, King Qu Wentai provided Xuanzang with introductions to all of the kings on his itinerary and also gave him sufficient supplies for his journey, without which Xuanzang’s pilgrimage may never have happened. By this point Xuanzang had achieved the reputation of an accredited scholar in China. In 630, Xuanzang embarked on a pilgrimage that would last just over 16 years. He visited many monasteries and religious sites on his journey, including the site where Buddha supposedly descended from heaven in Sankasya[2], his birthplace in Kapilavastu (southern Nepal), and the site of his death in Kusinagara (eastern India).

The most momentous stop on his journey was at the Nalanda Monastery, the most prestigious academic establishment in India at the time, which was located southwest of modern-day Bihar city. Nalanda consisted of some ten huge temples and, at that time, housed over ten thousand monks. According to legend, Silabhadra (529-645), the abbot of Nalanda, had considered committing suicide after years of suffering from illness when he was supposedly visited by deities in a dream. They commanded him to await the arrival of a Chinese monk who they claimed would spread the Mahayana[3] tradition across the world.

Silabhadra believed Xuanzang’s arrival fulfilled this prophecy and made Xuanzang his disciple. Under Silabhadra’s guidance, Xuanzang furthered his study of the Yogācāra branch of Buddhism. Yogācāra Buddhism is also called the Idealistic School. The central concept of this school is borrowed from a statement by the monk Vasubandhu, who said: “All this world is ideation only”. The basic concept of Yogācāra Buddhism is that the external world is merely a fabrication of our consciousness and does not actually exist, it is our internal ideas and past experiences that form what we perceive to be the outer world. The “real” world is simply our consciousness, so it is also sometimes referred to as the Consciousness Only branch of Buddhism.

Silabhadra believed Xuanzang’s arrival fulfilled this prophecy and made Xuanzang his disciple. Under Silabhadra’s guidance, Xuanzang furthered his study of the Yogācāra branch of Buddhism. Yogācāra Buddhism is also called the Idealistic School. The central concept of this school is borrowed from a statement by the monk Vasubandhu, who said: “All this world is ideation only”. The basic concept of Yogācāra Buddhism is that the external world is merely a fabrication of our consciousness and does not actually exist, it is our internal ideas and past experiences that form what we perceive to be the outer world. The “real” world is simply our consciousness, so it is also sometimes referred to as the Consciousness Only branch of Buddhism.

On leaving Nalanda, Xuanzang continued his pilgrimage until sometime between 643 and 644, when he decided to return to China. In 645 he finally arrived back in Chang’an and a great procession welcomed his return. He was immediately offered a ministerial position by Emperor Taizong but politely declined.

Religious Works

Xuanzang returned to China with seven statues of Buddha, over a hundred Buddhist relics and over 600 Buddhist texts. It was his aim to translate as many of these texts as he could so, with the support of the Emperor, he eventually masterminded the construction of the Giant Wild Goose Pagoda in Da Ci’en Temple, where he translated these works with the help of his fellow monks. In his lifetime, he was only able to translate about 75 of these texts into Chinese, which numbered about 1,300 sutras[4].

As a translator, Xuanzang wanted to present Buddhist texts to the Chinese in their entirety and so became well-known for his unabridged translations. When several of the original Indian scriptures were lost, his precise translations of them survived, meaning they have been preserved for posterity. An example of this is his translation of the Heart Sutra, which is the standard translation used by Buddhists today.

He also founded the Faxiang School of Buddhism based on his studies. During his lifetime, the school celebrated great popularity. Tragically, after his death, its popularity gradually declined but its teachings on consciousness, Karma, and other Buddhist principles were passed on to other, more successful schools, such as the Hossō School, which was one of the most influential Buddhist schools in Japan.

Literary Works

With the help of the monk Bianji, Xuanzang wrote one of the most famous literary works of the Tang Dynasty: Records of the Western Regions of the Great Tang Dynasty. It is sometimes referred to as Pilgrim to the West in the Tang Dynasty and Great Tang Records on the Western Regions. This novel is an invaluable academic resource because it records the geography, people, customs, history, religions, languages and cultures of about 140 countries that Xuanzang visited.

His travelogue inspired the famous Chinese epic Journey to the West by Wu Cheng’en. This novel was written in the 16th century during the Ming dynasty, around nine centuries after Xuanzang’s death. It is one of the Four Great Classical Novels of China. Outside of China, the abridged translation version Monkey by Arthur Waley is more well-known. In the novel, Xuanzhang is the reincarnation of the Golden Cicada, an original disciple of Buddha, and is protected on his pilgrimage by three supernatural beings, the most famous of which is the Monkey King.

His travelogue inspired the famous Chinese epic Journey to the West by Wu Cheng’en. This novel was written in the 16th century during the Ming dynasty, around nine centuries after Xuanzang’s death. It is one of the Four Great Classical Novels of China. Outside of China, the abridged translation version Monkey by Arthur Waley is more well-known. In the novel, Xuanzhang is the reincarnation of the Golden Cicada, an original disciple of Buddha, and is protected on his pilgrimage by three supernatural beings, the most famous of which is the Monkey King.

During the Tang Dynasty, Xuanzang was considered such a significant figure that, after his death, Emperor Gaozong cancelled all imperial audiences for three days in order to grieve. He was a pivotal figure in the development of Buddhist theory and his travelogues have given modern historians invaluable information about ethnic peoples and countries that have long been extinct. Modest and pious though he was, Xuanzang has arguably had a more powerful international impact than most emperors.

[1] Göktürks: A now extinct nomadic group of people, sometimes known as the Türks or the Ashina/Açina Turks, who were of Turkic descent and came from medieval Inner Asia.

[2] Sankasya: An ancient city in India that has since disappeared. It is sometimes known as Sankassa, Sankasia or Sankissa.

[3] Mahayana: One of the branches of Buddhism.

[4] Sutra: One of the sermons of the historical Buddha

Zhaoling Mausoleum

So utterly stunning is the site of Zhaoling Mausoleum that it has been the subject of Chinese poetry throughout the ages, from the Tang Dynasty (618-907) right through to the present day. The mausoleum itself has been carved into Jiuzong Mountain, about 83 kilometres (52 miles) away from Xi’an city centre. It is sometimes referred to simply as Zhao Mausoleum but is not to be confused with the mausoleum of the second Qing Emperor Huang Taji which shares the same name. Zhaoling Mausoleum was the final resting place of Emperor Taizong, the second emperor of the Tang Dynasty, and his wife, Empress Wende. It is phenomenal in its design, monumental in its scale and it completely revolutionised the way tombs were built during the Tang Dynasty. It is not only the largest Tang Mausoleum in China but is also the largest known royal mausoleum in the whole world. In its former glory, it was once a place that seemed almost ethereal in its grandeur. Nowadays, though it has suffered from the blows of time, it still provides a fascinating insight into the feudal system that led to modern China as we know it today.

Building of the mausoleum began over 1,300 years ago, in 636 A.D., and, although it only officially took 13 years to complete, it was added to and renovated over a period of 107 years. It was the first royal mausoleum to have been built into a mountain face, as oppose to the traditional burial mound on flat land. Supposedly the idea for building the mausoleum on Jiuzong Mountain came when the Empress Wende, being well-known for her humility, was on her deathbed and asked for a simple and frugal burial, saying “please bury me on the mountain and do not heap the grave”.

This gave Emperor Taizong a brilliant idea. He realized that the mountain, which is 1,188 metres above sea level and surrounded by the Jingshui River at its front and the Weishui River at its rear, was not only a magnificent place for a mausoleum but was also acted as a natural protective barrier against thieves and looters. Thus Emperor Taizong masterminded the building of his mausoleum and enlisted the help of the famous Tang technicians and painters Yan Lide and Yan Liben in its design. The mausoleum stretches over 200 square kilometres (88 square miles) and is split into sections above and below ground. The tomb passage alone, which leads to the tomb of Emperor Taizong, is 230 metres long and is guarded by five stone gates. In order to further deter looters from his tomb, Emperor Taizong even went so far as to write an inscription on the outside of the mausoleum which states: “A ruler takes the whole land under Heaven as his home. Why should he keep treasures within his tomb, possessing them as his private property?”. The implication was that the tomb was empty, as Emperor Taizong saw no reason to take his worldly goods to the grave, but this is in fact very far from the truth.

The mausoleum has nearly 200 satellite tombs that house famous ministers, members of the royal family and high ranking officials, but these satellite tombs are all further down the mountain than the Emperor’s tomb to symbolise his authority over them. It is the only mausoleum that exhibits the five styles of satellite tombs. Each tomb represents the relationship that the deceased had to the emperor. For example, the tomb of the princesses, the daughters of Emperor Taizong and Empress Wende, are located near to their father’s tomb and have either paired mounds at one end or are topped by a mound in an inverted dipper shape with four earthwork mounds. By contrast, daughters of Emperor Taizong born of concubines are further away from their father’s tomb and have a much simpler structure. This diversity creates a stunning yet surreal landscape that Tang Dynaty poet Du Fu described in his poem “Revisiting Zhaoling Mausoleum” as such:

“A line of tombs winds skyward up the slope

Where mountain beasts keep to their leafy lair;

I peer along a pine and cypress lane

Only clouds of sunset hanging in the air.”

Yet these satellite tombs are just the beginning of what was and still is a very lavish affair. Above ground, there once stood a complex that was unmatched in its splendour, including the Xuanwu Gate on the north side, the watchtower, the Zhuque Gate, Xian Hall and the sacrificial altar. This complex was once referred to as a miniature “Imperial City” because of its sheer size. Now all that remains are the Six Steeds of Zhaoling, the base of the sacrificial altar and a stone sparrow ornament from the ridge of the Xian Hall’s roof that is 1.5 metres in height. The size of this stone ornament alone gives you an idea of the scale of the building that once supported it.

The cemetery itself is still covered in the rich green pines, cypresses, huge Chinese scholar trees and poplars that earned it the name “the City of Pines”. The late Tang poet Liu Cang once wrote: “Entering the site of the underground palace along the mountain ridge, you will feel the chill of shady pines as if at midnight”. In this one sentence, Liu Cang captures the otherworldly nature of the mausoleum that makes it a site of such intrigue, even to this day. Though the surface buildings are gone, the mausoleum and the City of Pines still remain, untouched and unfaltering in their surreal majesty.

Only 37 of the satellite tombs have been excavated, but most of the artifacts that were found in these tombs are exhibited in the Zhaoling Museum. There you will find gorgeous Chinese porcelain, red Chinese pottery, painted pottery, glazed pottery, and tri-coloured glazed pottery from the Tang Dynasty. This pottery often takes the form of figurines, some of which, such as the figurines of ethnic minorities, demonstrate the close relationship that Emperor Taizong had with various ethnic minority groups during his reign. There are even a few glazed camels carrying silk cloth, as they would have done along the Silk Road over a thousand years ago. You’ll also find brightly coloured ancient paintings and murals depicting nobles and their life styles, from their frequent business trips to their leisure time spent singing, dancing and playing games, from ladies-in-waiting to courtiers. The museum houses one of three special official hats, personally made by Emperor Taizong, that were only awarded to the most distinguished courtiers and are incredibly rare.

Only 37 of the satellite tombs have been excavated, but most of the artifacts that were found in these tombs are exhibited in the Zhaoling Museum. There you will find gorgeous Chinese porcelain, red Chinese pottery, painted pottery, glazed pottery, and tri-coloured glazed pottery from the Tang Dynasty. This pottery often takes the form of figurines, some of which, such as the figurines of ethnic minorities, demonstrate the close relationship that Emperor Taizong had with various ethnic minority groups during his reign. There are even a few glazed camels carrying silk cloth, as they would have done along the Silk Road over a thousand years ago. You’ll also find brightly coloured ancient paintings and murals depicting nobles and their life styles, from their frequent business trips to their leisure time spent singing, dancing and playing games, from ladies-in-waiting to courtiers. The museum houses one of three special official hats, personally made by Emperor Taizong, that were only awarded to the most distinguished courtiers and are incredibly rare.

The Mausoleum and the Museum together present the chance to witness a true tableau of life in Feudal China. To witness the tombs snaking their way up the mountains, to feel the haunting chill of the pine tree cemetery, to gaze upon ancient tombstones hand-written by famous calligraphers, now also in their tombs, is an opportunity that can’t be missed. If you want to embed yourself in history and feel the thrill of living in a time when Emperors ruled and true heroic exploits breathed life to legends, then Zhaoling Mausoleum is the place for you.