The term “Muslim Quarter” may sound misleading, as it’s hard to believe that China has many local Muslims, and yet, nestled in the heart of Xi’an city, a bustling Muslim community has thrived for nearly a thousand years. Muslim Street, also known as Huimin Street, Muslim Snack Street or the Muslim Quarter, is a collective term used for a number of streets in Xi’an, including Beiyuanmen Street, Xiyangshi Street, and Huajue Lane. For the average tourist, it presents a fantastic opportunity to explore Chinese Muslim culture and get a real idea of what daily life is like for a Chinese Muslim. However, for the locals, this is the perfect place to whet their appetites on a balmy summers’ night and enjoy some of the fine delicacies that the Muslim district has to offer. In fact, the area has become famous for its undeniably delicious food, which includes both ethnically Muslim dishes and local Xi’an specialities. But before we get your mouth watering and your stomach rumbling, we’re sure you’d like to know more about how these Muslims came to live in a Chinese city.

It all began sometime between 209 B.C. and 9 A.D., during the Western Han Dynasty, when the Silk Road had just been established. The site of Xi’an city was, at the time, the ancient capital city known as Chang’an, which became the starting point for the Silk Road. Many diplomatic envoys, merchants and scholars from Persia or various Arabian countries were able to come to Chang’an thanks to the Silk Road and did so in order to follow various political, mercantile or scholarly pursuits. A number of these Persian and Arabian nationals decided to stay in Chang’an and settled on what is now the present-day Muslim Street. They came to be known by local people as the Hui (回) people. Over time, generation after generation of the Hui people thrived and multiplied, so that now approximately 60,000 Hui Muslims live in Xi’an city. In spite of their currently large population, they still form a very tight knit community thanks partly to their shared ethnicity and predominantly to their religion. Even to this day, there are 10 mosques on Muslim Street where Hui people can go to worship.

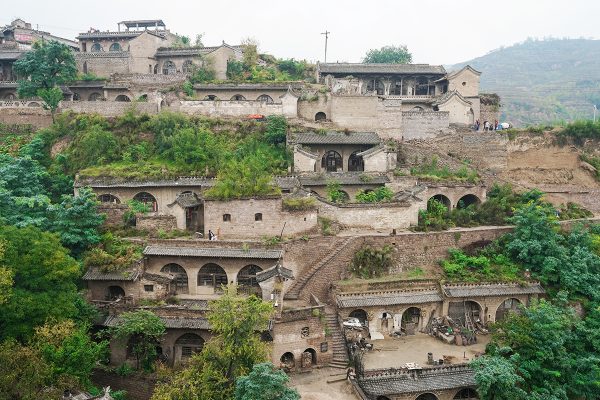

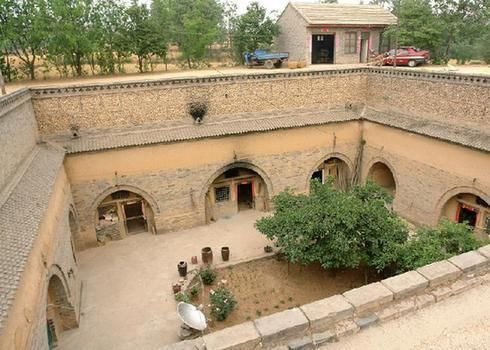

Nowadays, all of the shops and restaurants on Muslim Street are run by Hui people. Muslim Street itself is paved with blue flagstones and shaded on either side by trees, making it a beautiful place to go both day and night. Most of the ancient stores that line the main street of the Muslim Quarter were built during the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1912) Dynasties, so their architectural style is typical of that period. There are also a number of famous, ancient buildings in this district, including the Hanguang Gate of the Tang Dynasty, the Xicheng Gate Tower Cluster of the Ming Dynasty, the City God Temple (a Taoist Temple) and the Grand Mosque. Muslim Street is also very close to the Bell Tower and the Drum Tower, meaning it’s the perfect place to relax after a long day of sight-seeing.

Nowadays, all of the shops and restaurants on Muslim Street are run by Hui people. Muslim Street itself is paved with blue flagstones and shaded on either side by trees, making it a beautiful place to go both day and night. Most of the ancient stores that line the main street of the Muslim Quarter were built during the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1912) Dynasties, so their architectural style is typical of that period. There are also a number of famous, ancient buildings in this district, including the Hanguang Gate of the Tang Dynasty, the Xicheng Gate Tower Cluster of the Ming Dynasty, the City God Temple (a Taoist Temple) and the Grand Mosque. Muslim Street is also very close to the Bell Tower and the Drum Tower, meaning it’s the perfect place to relax after a long day of sight-seeing.

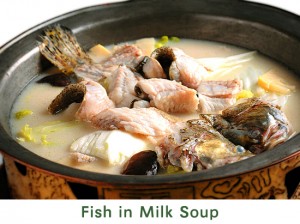

Yet it isn’t just the streets’ architectural beauty that draws the crowds every night. When dusk falls and the street lamps hanging from the restaurant eaves slowly light up, the Muslim Quarter comes to life. Locals and tourists alike flock there to taste some of the delicacies that Muslim Street has to offer. The two most popular dishes are Roujiamo, a bun filled with marinated mutton or beef that is sometimes referred to as a “Chinese Hamburger”, and Yangrou Paomo, a sumptuous mutton stew with vermicelli served with crumbly, melt-in-your-mouth, handmade flatbreads. Some Chinese celebrities have even gone so far as to say that Roujiamo is the tastiest dish in China!

And, if that doesn’t whet your appetite, then we’re sure you’ll succumb to the flavourful Liangpi cold noodles, the meaty Qishan noodles, the delectable soup buns and that irresistible favourite: dumplings. Not to mention that all of these dishes, from the Sun Family’s patented Yangrou Paomo to Wang’s Family Dumplings, are all handmade from recipes belonging to established Hui families that have been passed down for generations. Day or night, the Muslim Quarter is the perfect place to unwind and experience local culture. During the day you can immerse yourself in Hui culture by visiting the many markets in the area, in the afternoon you can visit Gaojia Dayuan and partake in one of their traditional puppet shows or shadow plays, and at night you can wander the streets people-watching or sit down to enjoy some delectable local cuisine. With all these tantalizing treats on offer, we guarantee that you simply won’t be able to resist a trip to Muslim Street.

And, if that doesn’t whet your appetite, then we’re sure you’ll succumb to the flavourful Liangpi cold noodles, the meaty Qishan noodles, the delectable soup buns and that irresistible favourite: dumplings. Not to mention that all of these dishes, from the Sun Family’s patented Yangrou Paomo to Wang’s Family Dumplings, are all handmade from recipes belonging to established Hui families that have been passed down for generations. Day or night, the Muslim Quarter is the perfect place to unwind and experience local culture. During the day you can immerse yourself in Hui culture by visiting the many markets in the area, in the afternoon you can visit Gaojia Dayuan and partake in one of their traditional puppet shows or shadow plays, and at night you can wander the streets people-watching or sit down to enjoy some delectable local cuisine. With all these tantalizing treats on offer, we guarantee that you simply won’t be able to resist a trip to Muslim Street.

Join our travel to visit the Muslim Street: Explore the Silk Road in China and Explore Chinese Culture through the Ages

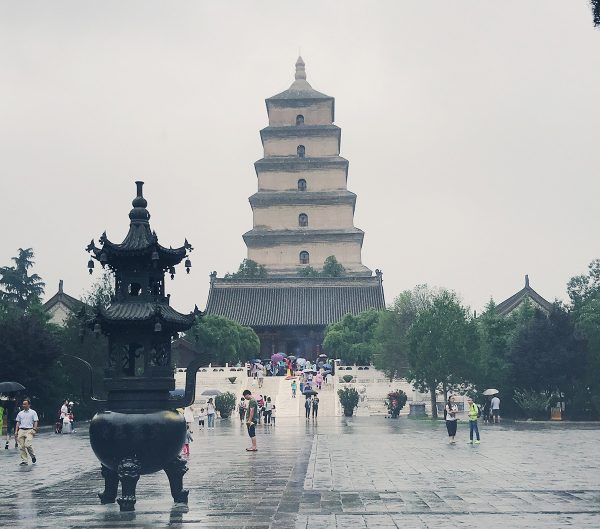

Nowadays the Great Wild Goose Pagoda is one of the most popular and flourishing tourist attractions in Xi’an. A climb to the top of the pagoda rewards you with a stunning view of Xi’an city and directly in front of the Pagoda, in the North Square of Da Ci’en Temple, you’ll find the largest musical water fountain in Asia. The water fountain covers a monumental 15,000 square metres and is divided into three parts: the Hundred-meter Waterfall Pool, the Eight-level Plunge Pool and the Prelude Music Pool. This musical light display seamlessly combines water features, like the 60 metre (197 ft.) wide, 20 metre (66ft.) high “Fire Fountain”, with beautiful music from the symphony “the Water Phantom of Tang”. There are regular performances every day but the show closes down from November through to January of every year.

Nowadays the Great Wild Goose Pagoda is one of the most popular and flourishing tourist attractions in Xi’an. A climb to the top of the pagoda rewards you with a stunning view of Xi’an city and directly in front of the Pagoda, in the North Square of Da Ci’en Temple, you’ll find the largest musical water fountain in Asia. The water fountain covers a monumental 15,000 square metres and is divided into three parts: the Hundred-meter Waterfall Pool, the Eight-level Plunge Pool and the Prelude Music Pool. This musical light display seamlessly combines water features, like the 60 metre (197 ft.) wide, 20 metre (66ft.) high “Fire Fountain”, with beautiful music from the symphony “the Water Phantom of Tang”. There are regular performances every day but the show closes down from November through to January of every year.

Xi’an was the first city in China to be introduced to Islam and, in 651 A.D., Emperor Gaozong of the Tang Dynasty officially allowed open practice of the religion. This allowed the Hui people, who are Muslims, to thrive in the area and thus a large concentration of them have remained in Xi’an. There are an estimated 50,000 Hui people in Xi’an and they form a tight knit community that oscillates primarily around Muslim Street and the Muslim Quarter.

Xi’an was the first city in China to be introduced to Islam and, in 651 A.D., Emperor Gaozong of the Tang Dynasty officially allowed open practice of the religion. This allowed the Hui people, who are Muslims, to thrive in the area and thus a large concentration of them have remained in Xi’an. There are an estimated 50,000 Hui people in Xi’an and they form a tight knit community that oscillates primarily around Muslim Street and the Muslim Quarter.

Nowadays the temple is full of interesting historical sites and stunning gardens that are regularly enjoyed by tourists and locals alike. The temple site is separated into four parts: the North, South, East, and West Squares. In the North Square you’ll find a copper statue of an ancient book that tells the story of how the Tang Dynasty rose to power. There are two Buddhist beacons in this square, both 9 metres tall, which are designed after the famous Mogao Grottoes in Dunhuang. You’ll also find statues of famous figures from the Tang Dynasty, such as the poets Li Bai, Du Fu, Wang Wei, and Han Yu, the unparalleled calligrapher Huai Su, and the “King of Chinese Medicine” Sun Simiao, scattered throughout the square.

Nowadays the temple is full of interesting historical sites and stunning gardens that are regularly enjoyed by tourists and locals alike. The temple site is separated into four parts: the North, South, East, and West Squares. In the North Square you’ll find a copper statue of an ancient book that tells the story of how the Tang Dynasty rose to power. There are two Buddhist beacons in this square, both 9 metres tall, which are designed after the famous Mogao Grottoes in Dunhuang. You’ll also find statues of famous figures from the Tang Dynasty, such as the poets Li Bai, Du Fu, Wang Wei, and Han Yu, the unparalleled calligrapher Huai Su, and the “King of Chinese Medicine” Sun Simiao, scattered throughout the square.

After the death of the Emperor in 210 B.C., the Mausoleum was hermetically-sealed and remained unopened for nearly 2,000 years. It wasn’t until 1974, when some farmers were attempting to dig a water-well near Mount Li, that Pit one of the Terracotta Army was accidentally unearthed. Archaeologists flocked to the site and began excavating the area, eventually discovering three more pits of Terracotta Warriors in the process. The warriors were all found arranged as if to protect the tomb from the east, which is where all of the states that were conquered by the Qin Dynasty lay. To date, approximately 8,000 soldiers, 130 chariots with 520 horses and 150 cavalry horses have been uncovered from these pits.

After the death of the Emperor in 210 B.C., the Mausoleum was hermetically-sealed and remained unopened for nearly 2,000 years. It wasn’t until 1974, when some farmers were attempting to dig a water-well near Mount Li, that Pit one of the Terracotta Army was accidentally unearthed. Archaeologists flocked to the site and began excavating the area, eventually discovering three more pits of Terracotta Warriors in the process. The warriors were all found arranged as if to protect the tomb from the east, which is where all of the states that were conquered by the Qin Dynasty lay. To date, approximately 8,000 soldiers, 130 chariots with 520 horses and 150 cavalry horses have been uncovered from these pits. The Museum of Qin Terracotta Warriors and Horses and the Qin Shi Huang Mausoleum have now been incorporated into one tourist attraction known as Emperor Qin Shi Huang’s Mausoleum Site Park. There you’ll find regular free shuttle buses that will take you from the site of the Terracotta Army to Lishan Garden. Lishan Garden acts as the perfect complement to the Terracotta Army as it contains Qin Shi Huang’s burial mound, ritual sacrifice pits, the Museum of Terracotta Acrobatics, the Museum of Terracotta Civil Officials, the Museum of Stone Armour and the Museum of Bronze Chariots and Horses. The Museum of Bronze Chariots and Horses is a wonderful exhibition of all the figures found throughout the pits that are crafted from bronze rather than terracotta. They loom out of their glass cases, lifelike in their shimmering skin. The other museums are based around pits where terracotta figures are still being excavated and present the perfect opportunity to watch a live archaeological dig. The chance to watch the Terracotta figures being unearthed and thus the opportunity to watch history being made is one that we know you won’t want to pass up. The only area that is not open to the public and has not been excavated is the main tomb, where the Emperor’s remains rest. In spite of an on-going debate as to whether the tomb should be opened or not, it is universally thought that it will remain undisturbed as a mark of respect to the Emperor.

The Museum of Qin Terracotta Warriors and Horses and the Qin Shi Huang Mausoleum have now been incorporated into one tourist attraction known as Emperor Qin Shi Huang’s Mausoleum Site Park. There you’ll find regular free shuttle buses that will take you from the site of the Terracotta Army to Lishan Garden. Lishan Garden acts as the perfect complement to the Terracotta Army as it contains Qin Shi Huang’s burial mound, ritual sacrifice pits, the Museum of Terracotta Acrobatics, the Museum of Terracotta Civil Officials, the Museum of Stone Armour and the Museum of Bronze Chariots and Horses. The Museum of Bronze Chariots and Horses is a wonderful exhibition of all the figures found throughout the pits that are crafted from bronze rather than terracotta. They loom out of their glass cases, lifelike in their shimmering skin. The other museums are based around pits where terracotta figures are still being excavated and present the perfect opportunity to watch a live archaeological dig. The chance to watch the Terracotta figures being unearthed and thus the opportunity to watch history being made is one that we know you won’t want to pass up. The only area that is not open to the public and has not been excavated is the main tomb, where the Emperor’s remains rest. In spite of an on-going debate as to whether the tomb should be opened or not, it is universally thought that it will remain undisturbed as a mark of respect to the Emperor.