Qinqiang opera is widely considered to be the forefather of all styles of Chinese opera. In ancient times, it was originally just called Qin opera and nowadays it is also known as Luantan opera, meaning “random pluck” or “strumming” opera. The name “Qin” derives from the fact that Qinqiang opera dates all the way back to the Qin Dynasty (221-206 B.C.) and its heritage stretches back over 2,500 years, making it one of the oldest forms of opera in China. This style of opera first originated from the folk songs of Shaanxi province and Gansu province, and eventually made its way to Beijing, where it heavily influenced the incredibly popular Peking opera.

As a style, it was refined during the Han Dynasty (206 B.C. – 220 A.D.), flourished during the Tang Dynasty (618-907), and was officially acknowledged as a style of opera by the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368). It went through a secondary period of refinement and maturation during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) and, by the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), it had spread throughout China. During the reign of Emperor Qianlong (1736-1795), there were over 36 Qinqiang troupes in the city of Xi’an alone. Supposedly Qinqiang opera started in the fields and farms of the northwestern provinces, when locals would shout to one another from across the fields. Eventually these locals developed a system of shouted songs to communicate with one another and this is where Qinqiang derives its distinctive “shouted out” style of singing. Thanks to this unusual singing style, Qinqiang opera is considered one of the “ten strange wonders of Shaanxi province”.

Along with this shouted style of singing, Qinqiang opera also incorporates bangzi[1] melodies. These are one of China’s Four Great Characteristic Melodies and Qinqiang is one of the most significant styles of Bangzi opera around today. The opera will usually be accompanied by several instruments, the most important of which is the banhu[2]. The banhu is either strummed or plucked, which is what earned this style of opera the name Luantan or “Random Pluck” opera. The characteristic arias of Qinqiang opera are deep, loud, piercing and bold, with singing of an impressively high pitch. There are two main types of arias in this style of opera: huanyin (joyous tunes) and kunyin (sad tunes). Though the huanyin are magnificent, the kunyin are widely considered to be the most hauntingly beautiful.

Along with this shouted style of singing, Qinqiang opera also incorporates bangzi[1] melodies. These are one of China’s Four Great Characteristic Melodies and Qinqiang is one of the most significant styles of Bangzi opera around today. The opera will usually be accompanied by several instruments, the most important of which is the banhu[2]. The banhu is either strummed or plucked, which is what earned this style of opera the name Luantan or “Random Pluck” opera. The characteristic arias of Qinqiang opera are deep, loud, piercing and bold, with singing of an impressively high pitch. There are two main types of arias in this style of opera: huanyin (joyous tunes) and kunyin (sad tunes). Though the huanyin are magnificent, the kunyin are widely considered to be the most hauntingly beautiful.

Qinqiang was one of the earliest forms of opera to focus on the expression of human emotion. Its use of exaggerated, stylised movements and facial expressions to imply actions, emotions, and events has been replicated in numerous other successive styles of opera. Most Qinqiang operas depict stories of ancient wars of resistance against foreign invaders, battles between good and evil, and the struggle against feudal oppression. They were designed to reflect the honesty, bravery and diligence of the common people of Northwest China.

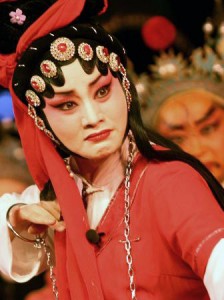

There are 13 character types in Qinqiang opera. These include four kinds of sheng or male characters, six kinds of dan or female characters, two kinds of jing or painted face characters, and one kind of chou or clown character. There are four major genres of Qinqiang opera, and this is predominantly due to the different dialects and folk music in the areas in which they were developed. Qinqiang is not just about the singing; it is a complete performance art and incorporates dancing, acrobatics and martial arts into every performance. Perhaps the most famous characteristic of Qinqiang is its style of fire-breathing, which has been copied in other successive styles of opera. Watching a performer in traditional dress breathe fire across the stage is a truly enthralling spectacle. The “hat dance” is another unique performance skill of Qinqiang opera, where performers will make a hat or object appear to dance on their head. Originally there were upwards of 10,000 Qinqiang works that were widely popular throughout China, of which only 4,700 remain. The Ghost’s Hate, Down the East River (下河东), The Golden Qilin or The Golden Unicorn (金麒麟), and The Port of Jiujiang (九江口) are just a handful of examples.

Unfortunately, since the 1980s the declining popularity of Chinese opera means that the tradition of Qinqiang opera has gradually started to disappear. However, many opera performers, opera enthusiasts, and government officials are committed to the preservation of this fine cultural art. In 2006 it was listed as a National Intangible World Heritage by the Chinese government and since then measures, such as government stipends for Qinqiang opera troupes and free tuition for anyone choosing to train in Qinqiang opera, have helped bolster the prevalence and popularity of this style of opera. There is now even a Qinqiang Opera Museum in Lanzhou, Gansu.

[1] Bangzi: A Chinese woodblock percussion instrument. Traditionally, two bangzi were used to keep the main tune during an opera, like a primitive form of metronome. Now the term bangzi or bangziqiang is widely used to refer to a type of melody used in Chinese opera.

[2] Banhu: A Chinese bowed stringed instrument. The soundbox is traditionally made from a coconut shell and the rest is made from wood. They have two strings.