There are numerous differences between Western and Chinese opera, the most notable of which is that Western opera tends to follow one long plotline, while Chinese opera is usually made up of several separate components, including circus-like stunts, short dramas, and story-telling portions. This difference is never more obvious than in Sichuan opera, which thrives on its magnificent spectacles and outrageous comedic skits to keep the audience wholly entertained. Employing expert clowns, illusionists, and acrobats, it’s a performance art that represents a true feast for the eyes!

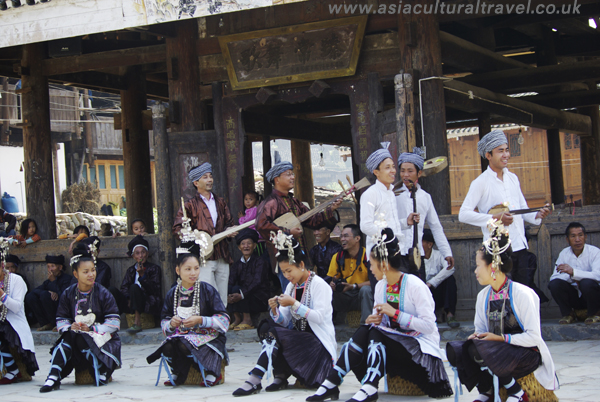

This style of opera originated from Sichuan province sometime during the end of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) and is actually comprised of five other, much older styles of opera. These five styles are known as Gaoqiang, Kunqiang, Huqing voice, Tanxi, and Dengdiao or Lantern theatre. Some of them date all the way back to the Three Kingdoms Period (220-280 AD) and represent some of the oldest styles of opera in China. As their popularity began to wane, a revival movement was begun during the early 20th century. In 1912, a reformer named Kang Zhilin established the Sanqing or “Three Celebrations” Company, which came to be known as one of the most prominent opera troupes in China.

It was Kang who combined these five historic styles to form traditional Sichuan opera. Many of the trademark physical movements and tropes of this style were masterminded by Kang himself. Over time, the style not only absorbed features from the other styles, but started to incorporate elements of the province’s local languages, customs, and folk songs. In this way, it is inextricably linked to Sichuan and its heart will always remain in the provincial capital of Chengdu.

It was Kang who combined these five historic styles to form traditional Sichuan opera. Many of the trademark physical movements and tropes of this style were masterminded by Kang himself. Over time, the style not only absorbed features from the other styles, but started to incorporate elements of the province’s local languages, customs, and folk songs. In this way, it is inextricably linked to Sichuan and its heart will always remain in the provincial capital of Chengdu.

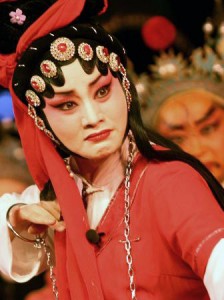

Nowadays Sichuan opera is said to boast over 3,000 stories, most of which date back to the Three Kingdoms Period, the Tang Dynasty (618-907), and the Song Dynasty (960-1279). Many of them are comedies and the style itself is renowned for its vivacity, good humour, and breath-taking stunts. The singing is usually in a higher pitch than Beijing opera and is also known for being less constrained. Unlike more dramatic styles of Chinese opera, the face paint is subtle and typically limited to the colours black, red, white, and grey. It’s missing the archetypal jing or villain character, so normally an evil character is simply indicated by a small patch of white paint in the middle of the face.

While the traditional formula for the opera is quite systematic, it is punctuated by lively acts of face-changing, beard-changing, fire-spitting, rolling light, and puppetry. The art of face-changing is unique to Chinese opera and has been a closely guarded secret for centuries. It is said the practice originated when ancient people would paint their faces to scare away wild animals, but has since been perfected into a performance art of the highest order. The act involves one performer changing their face mask within the blink of an eye, with masters of the art switching between a staggering 10 masks in less than 20 seconds!

While the traditional formula for the opera is quite systematic, it is punctuated by lively acts of face-changing, beard-changing, fire-spitting, rolling light, and puppetry. The art of face-changing is unique to Chinese opera and has been a closely guarded secret for centuries. It is said the practice originated when ancient people would paint their faces to scare away wild animals, but has since been perfected into a performance art of the highest order. The act involves one performer changing their face mask within the blink of an eye, with masters of the art switching between a staggering 10 masks in less than 20 seconds!

No one knows exactly how it is done, as the secret is only passed down among theatre families, but there are roughly three methods: the wiping mask, the blowing mask, and the pulling mask. During the wiping mask routine, the actor hides cosmetic paint in his eyebrows or sideburns. At the opportune moment, he will turn away from the audience and swiftly wipe the paint into a pattern on his face. Similarly, the blowing mask routine involves the actor holding a box of powdered cosmetics and blowing on it. Since the actor will have oiled his face beforehand, the powder will naturally fly up and adhere to his face.

The pulling mask routine, however, is by far the most popular and the most complicated. The masks are delicately painted beforehand on silk fabric, which is cut, attached to a silk thread, and lightly pasted to the face. Each one is gently laid on top of the other and the silk threads are hidden somewhere within the actor’s costume. With a sharp flick of his cloak, the actor is able to pull away each mask one by one, although the exact method is still a tantalising mystery. In short, we may never know what secrets are hidden behind the mask!

The different coloured masks are used to represent the actor’s characteristics and function to tell a simple story, much like a one-man monologue. For example, red represents someone who is steadfast, black signifies the character is righteous, green or blue symbolises that they are strong or violent, and white implies the person is treacherous. This veritable rainbow of traits is the ideal way for the performer to reflect their character’s hidden feelings without speaking, since the face-changing act contains no dialogue whatsoever. In some simplified versions of the act, the performer will simply pull on his beard and have it change colour from black to grey to white, in order to show displeasure or confusion.

In many cases, face-changing is combined with the fire-spitting act to add an extra dimension of complexity. While fire-spitting is not uncommon in performances throughout the world, actors in Sichuan opera are capable of spitting a fire column that is up to 2 metres (6.6 ft.) in height! In a similarly fiery display, the act known as rolling light involves the actor performing a series of complicated acrobatic moves while balancing a bowl of fire on is head.

In many cases, face-changing is combined with the fire-spitting act to add an extra dimension of complexity. While fire-spitting is not uncommon in performances throughout the world, actors in Sichuan opera are capable of spitting a fire column that is up to 2 metres (6.6 ft.) in height! In a similarly fiery display, the act known as rolling light involves the actor performing a series of complicated acrobatic moves while balancing a bowl of fire on is head.

The character is typically a clown and the set-up is normally that of a woman angry with her husband. For example, one skit involves a married couple arguing about the husband’s gambling. Throughout the course of the argument, the wife demands that the husband perform a series of increasingly difficult tasks while balancing the bowl on his head. Other highlights include the stick puppet and shadow puppet shows, which usually revolve around traditional Chinese mythology and folktales. With so much on offer, Sichuan opera is certainly one of the most diverse forms of Chinese opera and has something to suit everyone’s tastes!

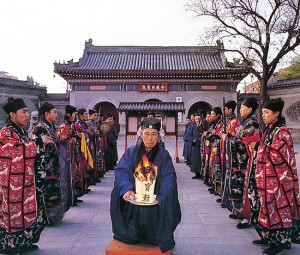

The Temple of the God (Creator) of Agriculture was the site of imperial sacrifices dedicated to the cult of Shennong, the Holy Farmer. It is located in the southern part of the city, directly to the west of the Temple of Heaven, and occupies a total area of three-square kilometres.

The Temple of the God (Creator) of Agriculture was the site of imperial sacrifices dedicated to the cult of Shennong, the Holy Farmer. It is located in the southern part of the city, directly to the west of the Temple of Heaven, and occupies a total area of three-square kilometres.