As wind whips the sand dunes across the Gobi Desert, the once illustrious Khara-Khoto or “Black City” is slowly being buried by sand. According to local rumour, it is inhabited only by ghosts and demons. Yet it wasn’t always a place of desolation and death. The city was founded by the Tangut people in 1032 as the capital of their Western Xia Dynasty (1038–1227) and soon rose to become a thriving trade hub. The fortified city was captured by Genghis Khan in 1226 but, far from being lost, it actually thrived under Mongol rule. During the Mongol-led Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368), it expanded to three times its original size and was even visited by the intrepid explorer Marco Polo, who referred to it by its Tangut name of Etzina. The Tangut people, though subservient to the Mongolians, were able to enjoy a life of peace for a further 150 years under their rule.

However, as the Yuan Dynasty began to collapse, disaster loomed on the horizon. After a crushing defeat at Jiayu Pass in Gansu province, the Mongolians were driven out of China by the armies of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644). Many of the Mongolian troops made it to Khara-Khoto and were able to settle there, as the Ming army chose to concentrate on returning order to the provinces of China rather than pursue them. While the Ming Dynasty consolidated its power in China, the Mongolian armies waited on the outskirts and greedily eyed the possibility of conquering the country again. By 1372, Mongolian troops had begun massing at Khara-Khoto with the eventual aim of reinvading China. It was this bold move that would seal their fate.

No one knows exactly how Khara-Khoto fell, but local legend states that Ming troops laid siege to the city in that same year. The city was so well-fortified that they were unable to take it by military force, so instead resorted to far more cunning tactics! They found a way to divert the nearby Ejin or “Black” River, which was the city’s only water source. By denying it this precious lifeblood, the Ming troops choked the city without ever needing to set foot inside of its walls. As their gardens and wells began to dry up, the people of Khara-Khoto realised that they must make a terrible choice: die of thirst, or face the Ming soldiers in combat.

No one knows exactly how Khara-Khoto fell, but local legend states that Ming troops laid siege to the city in that same year. The city was so well-fortified that they were unable to take it by military force, so instead resorted to far more cunning tactics! They found a way to divert the nearby Ejin or “Black” River, which was the city’s only water source. By denying it this precious lifeblood, the Ming troops choked the city without ever needing to set foot inside of its walls. As their gardens and wells began to dry up, the people of Khara-Khoto realised that they must make a terrible choice: die of thirst, or face the Ming soldiers in combat.

A Mongol military general named Khara Bator supposedly became so crazed by this plight that he murdered his wife and children before committed suicide, although another version of the rumour states that he made a breach in the northwestern corner of the city wall and escaped through it. Upon either his demise or his escape, the remaining Mongolian soldiers tried to hold out within the fortress. When the Ming armies finally attacked, they slaughtered the soldiers like cattle. Thereafter, the city was permanently abandoned and fell to ruin. It would be another 600 years before someone would finally uncover this ancient metropolis from beneath the dusty sand.

When Russian explorers Grigory Potanin and Vladimir Obruchev heard rumours that an ancient city lay somewhere downstream along the Ejin River, it sparked the interest of the Asiatic Museum (now the Institute of Oriental Studies) in St. Petersburg. In 1907, they promptly launched a new Mongol-Sichuan expedition under the command of Pyotr Kuzmich Kozlov. Within a year, Kozlov had discovered the Khara-Khoto ruins and obtained permission to dig in the site from a local Torghut lord named Dashi Beile, in exchange for a free dinner and a gramophone!

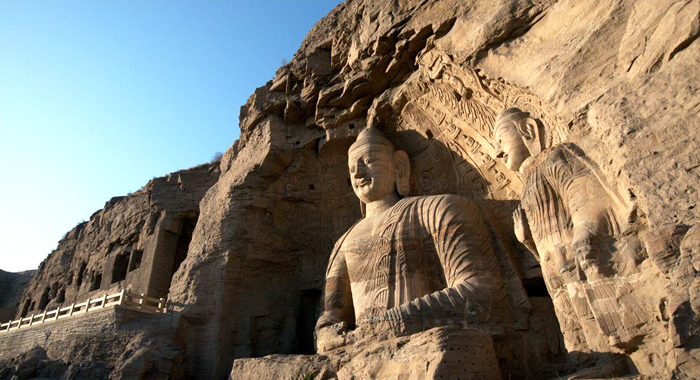

During his initial excavation, he uncovered over 2,000 books, scrolls, and manuscripts in the forgotten Tangut language, including a Chinese-Tangut dictionary titled Pearl in the Palm. These treasures were sent back to St. Petersburg, along with Buddhist statues, texts, and woodcuts that were found in a stupa¹ outside of the city walls. Over time, further excavations would produce thousands more manuscripts, daily items, and works of religious art, and the site would even be visited by famous archaeologists such as Aurel Stein and Langdon Warner. While these precious relics have all been carefully housed in museums across the globe, Khara-Khoto remains open for any visitor daring enough to wander its haunted ruins.

During his initial excavation, he uncovered over 2,000 books, scrolls, and manuscripts in the forgotten Tangut language, including a Chinese-Tangut dictionary titled Pearl in the Palm. These treasures were sent back to St. Petersburg, along with Buddhist statues, texts, and woodcuts that were found in a stupa¹ outside of the city walls. Over time, further excavations would produce thousands more manuscripts, daily items, and works of religious art, and the site would even be visited by famous archaeologists such as Aurel Stein and Langdon Warner. While these precious relics have all been carefully housed in museums across the globe, Khara-Khoto remains open for any visitor daring enough to wander its haunted ruins.

Nowadays all that is left of this venerable city are the 9-metre (30 ft.) high ramparts, the 4-metre (12 ft.) thick outer walls, a 12-metre (39 ft.) high pagoda shaped like an upturned bowl, an assortment of crumbling mud houses, and the remnants of what appears to be a mosque on the outskirts of the city walls. With the Ejin River largely dried up and the sand dunes constantly moving on the wind, navigating the desert surrounding the city is treacherous and must be done with extreme care. If you’re feeling particularly brave, you can pitch a tent and stay overnight. Only then might you witness the fuel-less flames that burn for hours, the balls of light dancing in the desolate dark, and the sounds of raucous banging from unknown sources as the ghosts of Khara-Khoto welcome you to their humble home!

Stupa: A hemispherical structure with a small interior designed for storing Buddhist relics and for private meditation.

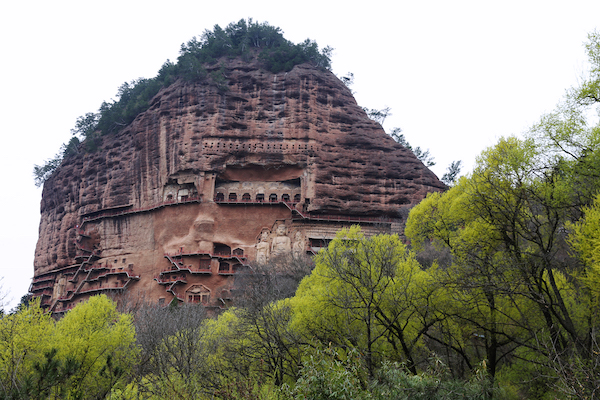

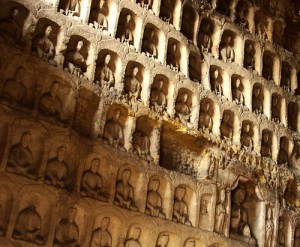

The mountain itself sits at an altitude of 1,700 metres (5,577 ft.) and is named “Maiji”, meaning “wheat”, “corn”, or “grain stack”, due to its unusual appearance. It is tall in the middle, narrow at the bottom, and completely flat on the top, meaning it resembles a stack of wheat. So be careful when you take photographs of this scenic spot, or they might come out a little grainy! The caves are separated by number, with numbers 1 to 50 on the western cliff-face and numbers 51-191 on the eastern cliff-face.

The mountain itself sits at an altitude of 1,700 metres (5,577 ft.) and is named “Maiji”, meaning “wheat”, “corn”, or “grain stack”, due to its unusual appearance. It is tall in the middle, narrow at the bottom, and completely flat on the top, meaning it resembles a stack of wheat. So be careful when you take photographs of this scenic spot, or they might come out a little grainy! The caves are separated by number, with numbers 1 to 50 on the western cliff-face and numbers 51-191 on the eastern cliff-face. Construction of the grottoes reached its peak during the Northern Wei (386-535), Western Wei (535–557), and Northern Zhou (557-581) dynasties, but continued well into the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1912) dynasties, representing over 1,000 years’ worth of effort and artistry. The earlier caves are far more simplistic in design and mainly feature a seated Buddha flanked by bodhisattvas

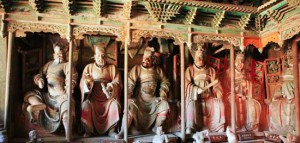

Construction of the grottoes reached its peak during the Northern Wei (386-535), Western Wei (535–557), and Northern Zhou (557-581) dynasties, but continued well into the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1912) dynasties, representing over 1,000 years’ worth of effort and artistry. The earlier caves are far more simplistic in design and mainly feature a seated Buddha flanked by bodhisattvas The bodhisattvas who usually accompany Amitābha are Avalokitesvara on his right and Mahasthamaprapta on his left. Avalokitesvara is the most identifiable, as he is typically depicted with an image of Amitābha on his headdress and a small water flask in his hands. In a few more hundred years, Avalokitesvara will change genders and eventually reappear in the grottoes as the bodhisattva of mercy, known as Guanyin. That being said, when it comes to eternal enlightenment, it doesn’t really matter if you’re a man or a woman! Other statues include those of the historical Shakyamuni

The bodhisattvas who usually accompany Amitābha are Avalokitesvara on his right and Mahasthamaprapta on his left. Avalokitesvara is the most identifiable, as he is typically depicted with an image of Amitābha on his headdress and a small water flask in his hands. In a few more hundred years, Avalokitesvara will change genders and eventually reappear in the grottoes as the bodhisattva of mercy, known as Guanyin. That being said, when it comes to eternal enlightenment, it doesn’t really matter if you’re a man or a woman! Other statues include those of the historical Shakyamuni

When Islam swept through Central Asia during the 15th and 16th centuries, much of Xinjiang’s population converted and the Bezeklik Caves were completely abandoned. During the ensuing religious clashes, many of the murals within the caves were destroyed. Since Muslims believe that images of sentient beings are blasphemous, the figures in several of the paintings have noticeably had their eyes scratched out or their faces obscured. This means some of the scenes within the caves now resemble a set from a horror movie!

When Islam swept through Central Asia during the 15th and 16th centuries, much of Xinjiang’s population converted and the Bezeklik Caves were completely abandoned. During the ensuing religious clashes, many of the murals within the caves were destroyed. Since Muslims believe that images of sentient beings are blasphemous, the figures in several of the paintings have noticeably had their eyes scratched out or their faces obscured. This means some of the scenes within the caves now resemble a set from a horror movie!