In 690, Empress Wu Zetian briefly put an end to the Tang Dynasty and established her own short-lived Zhou Dynasty (690-705). However, after just 15 years, Emperor Zhongzong was able to overthrow her and re-establish the Tang Dynasty. The imperial officials breathed a sigh of relief, believing that their lady troubles were finally over. How wrong they were! Although Wu Zetian was the only woman in Chinese history to ever openly rule China, plenty of women after her would continue to exert control over the throne. This included Emperor Zhongzong’s wife, Empress Wei, whose regime of corruption crippled the imperial court.

When Zhongzong finally died in 710, it was even rumoured that she had poisoned him! Yet, in a bizarre twist of fate, her attempts to establish herself as ruler were thwarted by Empress Wu Zetian’s formidable daughter, Princess Taiping. After all, the ambitious apple doesn’t fall far from the tree! Thanks to her help, Li Longji was able to restore his father, Emperor Ruizong, to the throne. However, just two years later, Ruizong yielded the throne to Li, who became the venerable Emperor Xuanzong.

Xuanzong’s 44-year reign would later come to be recognised as the apex of the Tang Dynasty, which was no mean feat when you consider that the Tang lasted for nearly 300 years! During his reign, the tax system was reorganised, the canal network was restored to its former glory, and cultural integration between the north and the south was expedited. Xuanzong was celebrated as a progressive and benevolent ruler, who ushered in an era of wealth and prosperity.

However, his authority was frequently challenged by a formidable foreign enemy. From 714 onwards, the Tibetans continually invaded China’s northwest, and Xuanzong was forced to establish a number of strategic military provinces along the northern borders. Each of these garrisons was under the command of an appointed military governor, who controlled large stretches of territory and enormous numbers of troops.

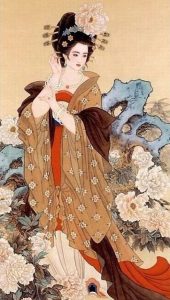

Xuanzong’s reliance on his advisers and military governors would prove to be both his strength and his weakness. From 737 onwards, he rested almost all of his confidence in his long-serving chancellor Li Linfu and, as time went on, he withdrew from political affairs to enjoy the pleasures of the palace. In 745, he became deeply infatuated with a concubine named Yang Guifei and, thanks to her influence, her brother Yang Guozhong rose to become Li’s major political rival. On Li’s death in 752, Yang dominated the imperial court unchallenged, although he lacked Li’s political ability and experience.

Meanwhile, during the 740s, a general of Göktürk[1] and Sogdian origin named An Lushan became military governor of three northeastern garrisons. He had risen to power largely thanks to the patronage of Li Linfu and, when Li passed away, he became the staunch rival of Yang Guozhong. As Yang developed a stranglehold on the imperial court, An continued to build up his military forces. During the 750s, a number of martial defeats against foreign invaders meant that the Tang Empire was severely weakened.

The An Lushan Rebellion

Taking full advantage of the unstable political climate, An Lushan launched a vicious rebellion in 755. By 757, he had captured the imperial capital of Chang’an (modern-day Xi’an) and Xuanzong was forced to flee. Not long thereafter, the crown prince usurped the throne as Emperor Suzong. Although An Lushan was murdered by one of his men in that same year, the brutal An Lushan Rebellion lasted for another 6 years! It was perpetuated first by An’s son, then by his trusted general Shi Siming, and finally by Shi’s son, Shi Chaoyi. Talk about a family affair!

When the rebellion was finally quashed in 763, the empire was practically in ruins. Yet, rather than punish the generals responsible for the rebellion, many of them were appointed as imperial governors instead. In this case, the punishment certainly didn’t fit the crime! The province of Hebei was divided up into four new provinces, which were each surrendered to these military governors or jiedushi, while Shandong province was settled by An Lushan’s former garrison troops.

Unsurprisingly, the central government held little influence within these provinces. The jiedushi wielded such political power that they were able to maintain their own armies, collect their own taxes, and choose their own heirs. These were privileges normally reserved only for the Emperor himself! By this point, the Tang Dynasty was firmly in decline.

Even in provinces that weren’t ruled by jiedushi, there were serious problems with provincial separatism. In northern China, many of the provinces were administered by military governments due to the constant threat of foreign invasions on the northern borders. In the south of China, high-ranking officials who had lost favour with the imperial court were frequently appointed as civil governors. In both instances, these provincial governments exercised a great deal of autonomy throughout the reigns of Emperor Suzong and his heir, Emperor Daizong.

Fortunately, Daizong was succeeded by Emperor Dezong, who proved to be a resilient and intelligent ruler. However, Dezong’s attempts to openly challenge the jiedushi ended in abject failure. From 781 to 786, a wave of revolts broke out throughout the northeast and caused widespread destruction on a similar scale to the An Lushan Rebellion. It only ended when the rebels fell out amongst themselves and had to disband, resulting in the situation essentially returning to what it had been before the rebellion! Thereafter, Dezong was far more cautious when it came to the jiedushi, although his reign was marked by steady progression in other areas of governance. In particular, his tax system remained the basis for the tax structure right up until the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644).

On Dezong’s death in 805, the throne briefly passed to the ineffective Emperor Shunzong before he was replaced with Emperor Xianzong. Like Dezong, Xianzong proved to be a firm and efficient ruler. Thanks to a colossal palace army, he was able to crush a number of rebellions throughout the country and was eventually able to restore authority to the central government. That being said, a large part of Xianzong’s success had been thanks to the work of the palace eunuchs. During his reign, their role became increasingly more important not just as sources of information, but also as active political agents that were able to intervene in official affairs.

While Xianzong concentrated his efforts on his political enemies, he never suspected that it would be his allies who would prove to be his undoing. In 820, he was murdered by his eunuch attendants and replaced with his son, Emperor Muzong. From then onwards, the palace eunuchs exerted considerable influence over the country’s governance and civil unrest spread rapidly throughout the country.

The Fall of the Tang Dynasty

By the time Emperor Xizong took the throne in 873, the empire was on the brink of collapse. Severe droughts prompted a wave of peasant uprisings, the most serious of which was led by a man named Huang Chao. In 880, his forces marched north and took control of both Luoyang and Chang’an. While he was eventually forced to abandon Chang’an in 883, his rebellion left the Tang court virtually powerless. Bandit gangs wreaked havoc on the Chinese countryside, and the imperial court was besieged by powerful military leaders.

One of these was Zhu Wen, a salt smuggler who had served under Huang Chao but had betrayed him by allying with the Tang. In 907, he deposed the reigning Emperor Ai and took the throne for himself, establishing the Later Liang Dynasty (907–923). However, the Tang only controlled a small portion of China’s territory at the time, so Zhu Wen had plenty of other warlords to contend with. With the country thus fractured into a number of independent kingdoms, the Tang Dynasty officially ended and an era of great instability known as the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms Period (907-960) was ushered in.

[1] Göktürks: A now extinct nomadic group of people, sometimes known as the Türks or the Ashina/Açina Turks, who were of Turkic descent and came from medieval Inner Asia.