(581-618)

During the preceding Northern and Southern Dynasties Period (420-589), the north and south of China were fractured by a series of rival dynasties. While the south was ruled by the Chen Dynasty (557–589), the north was split between the Northern Zhou (557–581) and Northern Qi (550–577) dynasties. When the Northern Zhou finally conquered the Northern Qi Dynasty in 577, it seemed that the Chen Dynasty’s fate was sealed. Yet internal conflicts in the imperial court prevented the Northern Zhou from advancing south.

During a political coup in 581, the reigning Emperor Xuan’s father-in-law, Yang Jian, was able to seize power and established the Sui Dynasty (581-618) under the regal name Emperor Wen. From there he turned his gaze south and, thanks to his superlative military strategies, he annexed the Chen Dynasty just eight years later. For the first time in over 300 years, China was firmly and sustainably unified! Like the Qin Dynasty (221-206 BC), which also united China after a period of great discord, the Sui Dynasty’s short duration belies the great political and cultural impact it had on China.

In just 37 years, the Sui emperors restructured the governmental system, restored order to the country’s farming dynamic, re-established the importance of Confucianism, and constructed several integral edifices. In short, they laid the foundation for the succeeding Tang Dynasty (618-907), which is regarded as a golden era in Chinese history. However, much like the Qin Dynasty, it would be ambitious construction projects and costly wars that would overstretch the empire’s resources, resulting in widespread discontent and eventually full scale rebellions.

The Reign of Emperor Wen

One of Emperor Wen’s first acts as ruler was to fortify the country’s frontiers by making extensive repairs to the Great Wall, as they faced significant threats on all sides. In particular, the formidable Turkic Tujue people to the north controlled large stretches of territory and posed a significant risk to the burgeoning Sui Empire. In this instance, Emperor Wen used his cunning nature to his advantage. At the time, the Tujue Khaganate (552–744) was suffering due to intense disputes between the Western and Eastern Tujue.

Through various diplomatic manoeuvres, Emperor Wen backed the Western Tujue and effectively sped up the separation of the Tujue Empire. The Eastern Tujue overtook the territory along China’s northern frontier, while the Western Tujue controlled a vast area stretching from the Tarim Basin into Central Asia. Throughout his reign, he continued to encourage factional strife amongst the Eastern and Western Tujue. It seemed he really loved stirring the pot!

Yet Emperor Wen’s administrative skills didn’t end there. He was a frugal ruler and accumulated great financial reserves. This allowed him to reduce taxes, re-organise the field allocation system, and establish the Three Departments and Six Ministries system of government. His political reforms were widely celebrated and eventually became the model for numerous succeeding dynasties, right up until the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912).

In an effort to establish a link with the Han Dynasty (206 BC–220 AD), which was already regarded as a golden age in Chinese history, he re-instated Confucian court rituals, curried favour with Confucian scholars, and employed several of them as government officials. However, he knew he simply couldn’t ignore a certain foreign religion that had catapulted into popularity during the preceding Northern and Southern Dynasties Period. Thus he converted to Buddhism, encouraged his citizens to follow suit, and even tried to re-invent himself as a Buddhist Saint-King in order to further legitimise his right to rule. In this way, the religion continued to flourish throughout the Sui Dynasty.

The Reign of Emperor Yang

Unfortunately, as with many dynasties, things took a turn for the worse when Emperor Wen passed away in 604. He was succeeded by his son, Emperor Yang, who is regarded by many as an arrogant and depraved megalomaniac. Historical records have been particularly unkind to Emperor Yang, who began his reign in much the same way as his father had done. He revised the law to reduce criminal penalties, restored Confucian education, implemented the Confucian examination system that his father had created, and expanded his empire. Yet his greatest achievement was undoubtedly his efforts spent properly integrating the south into a unified China. He even married a princess from the southern state of Liang. Talk about taking your work home with you, literally!

Where before the imperial court was dominated by northwestern aristocratic families, now southern and northeastern scholars were given a chance to gain high-ranking political positions. However, his educational reforms and clemency towards the southern peoples earned him the scorn of the northern nomads, who gradually stopped supporting him. His decision to move the capital from northwestern Chang’an (modern-day Xi’an) to northeastern Luoyang only succeeded in alienating them further.

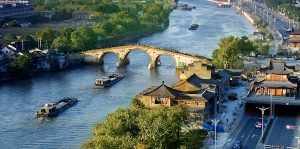

He expanded this new capital rapidly, adding palaces and a colossal imperial park that required a prodigious amount of labour. Yet his grandiose construction plans didn’t end there. In an attempt to further unify the empire and improve his chances of expanding it, he decided to develop the canal system. In 605, he extended the existing Bian Canal so that it linked Luoyang with the Huai River and thus with the Yangtze River, providing access to the southern capital of Jiangdu (present-day Yangzhou).

Another great canal was built linking Luoyang with the region surrounding modern-day Beijing, in preparation for military campaigns on the Korean frontier. By 611, all of the major river systems in northern China were connected, providing a direct route from the Yangtze River Delta to the northern frontier. Masses of forced labourers were made to work on these projects in appalling conditions, which were inordinately costly and caused widespread civil unrest. Although this canal system was to be Emperor Yang’s lasting legacy, it would also serve to be his downfall.

Another great canal was built linking Luoyang with the region surrounding modern-day Beijing, in preparation for military campaigns on the Korean frontier. By 611, all of the major river systems in northern China were connected, providing a direct route from the Yangtze River Delta to the northern frontier. Masses of forced labourers were made to work on these projects in appalling conditions, which were inordinately costly and caused widespread civil unrest. Although this canal system was to be Emperor Yang’s lasting legacy, it would also serve to be his downfall.

Yang’s aggressive foreign policy eventually led to him conquering the Champa State of central Nam Viet (modern-day Vietnam) and driving the Tuyuhun people out of Gansu and Qinghai provinces. Yet these small victories were undercut by one colossal military failure that effectively crippled the Sui Empire: Emperor Yang’s attempt to take over the Korean Goguryeo Kingdom. After the completion of his canal system, Emperor Yang sent droves of troops and supplies to the Korean frontier. It was estimated that, at one point, this army listed over 3,000 warships, up to 1.15 million infantry, and 50,000 cavalry. In short, Emperor Yang meant business! However, due to severe flooding and poor organisation, all four of his military campaigns ended in disaster. The loss of human life was immeasurable.

Fall of the Sui Empire

Minor revolts began to break out throughout the provinces of Shandong and Hebei, but Emperor Yang’s growing preoccupation with the war against the Goguryeo Kingdom meant he turned a blind eye to the severe internal problems his empire was suffering from. His people were demoralised, his military was crippled, and his economy was in ruins. The rebellions became so severe that in 616 he was forced to retreat to the southern capital of Jiangdu, since much of northern China had been conquered by rebel regimes. The rebel warlord Li Mi ruled the area surrounding Luoyang, while Dou Jiande controlled the northeast, Xue Ju dominated the northwest, and Li Yuan reigned over Shanxi province. However, while Li Mi, Dou Jiande, and Xue Ju fought against the imperial army, Li Yuan sided with the imperial court and declared war on all rebel armies.

Li Yuan proved to be the most martially savvy of them all, inflicting a great defeat on the Eastern Tujue and capturing the city of Chang’an in 617. In 618, Emperor Yang was murdered by his advisors at his palace in Jiangdu. Perhaps he should have learnt something from Julius Caesar! Although a Sui prince was briefly enthroned as Emperor Gong, Li Yuan swiftly deposed him and proclaimed himself Emperor Gaozu of the Tang Dynasty. Little did he know that he had just laid the foundation for one of the greatest eras in Chinese history.