Explore the Mystery of Tibetan Culture Festival by Festival 2024

Explore Uzbekistani Culture along the Ancient Silk Road

Explore the Birthplace of Chinese Civilisation

Tsoka Lake

Embedded deep within one of the remote mountain valleys of the Garzě Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Tsoka Lake appears like a small jewel embedded into the surrounding hillside. The lake itself only covers a surface area of around 3 square kilometres (1 sq. mi), but don’t let its small size fool you. As the old saying goes, big things often come in small packages! The name “tsoka” roughly translates to mean “the black water in the stone forest,” which is in reference to the lake’s characteristically dark waters and the surrounding snow-capped mountains that loom over it. As proof of the lake’s holy status, you’ll find numerous halls and buildings situated along its shores, which were all built in the traditional Tibetan style and together make up the Tsoka Monastery.

The monastery itself dates back to the 14th century and is one of few monasteries that follows the teachings of two different sects of Tibetan Buddhism. Although the Gelug or “Yellow Hat” sect of Tibetan Buddhism continues to be by far the most popular, monks living in the Tsoka Monastery follow a combination of teachings from the Nyingma and Kagyu sects, which rank alongside the Gelug sect as two of the four most important sects of Tibetan Buddhism. In fact, the Nyingma sect is widely considered to be the oldest, with a history that stretches all the way back to the 8th century!

Make your dream trip to the Huiyuan Monastery come true on our travel:

Yihun Lhatso

Resting at an altitude of a staggering 4,100 metres (13,500 ft.), Yihun Lhatso is a glacial alpine lake that shimmers like a sapphire embedded at the base of the surrounding snow-capped mountains. It can be found at the foot of Rongme Ngatra, which rises to a height of 6,168 metres (20,236 ft.) and is thus the tallest peak belonging to the Chola Mountains. Melted ice from the snowy cap of Rongme Ngatra makes its way down the steep mountainside until it eventually feeds into the lake, which is why the waters of the lake are breathtakingly pristine and crystal clear in appearance. If you are lucky, you may even spot herds of rare white-lipped deer grazing by its shore!

The lake received its name thanks to a rather sombre legend, which recounts the story of a Tibetan woman named Zhumu. Zhumu was the beloved concubine of a famous Tibetan folkloric figure named King Gesar, whose heroic deeds are the subject of The Epic of King Gesar. According to this legend, Zhumu decided to travel alone to the lake in order to contemplate its beauty, but she was so captivated by it that she couldn’t bring herself to leave. In the end, she was so drawn in that she began walking further and further into the lake, until she sunk beneath its azure waters. From then onward, the lake was known as Yihun Lhatso, which roughly translates to mean “the holy lake of the fallen heart” in reference to how Zhumu’s heart was taken in by its unparalleled beauty.

Alongside being a site of undeniably natural beauty, the lake is revered as a sacred place by the local Tibetan people. It is located within the Garzě Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture of Sichuan province, which once belonged to a region of the ancient Tibetan Empire known as Kham. The Tibetan people living in this region are culturally distinct from both the Tibetan people living in Tibet proper and those living in Qinghai province, so they are often referred to more specifically as Khampa Tibetans. For hundreds of years, these Khampa Tibetans have worshipped the lake as a holy place according to Tibetan Buddhism. Along the shore, you’ll find hundreds of boulders that have been carefully carved into what are known as mani stones.

Mani stones are any stone plates, rocks, or pebbles that have been inscribed with the six-syllabled Buddhist mantra known as “Om Mani Padme Hum.” They are often placed either on their own, in piles, or as part of walls and serve as a form of prayer or religious offering. As you wander along the shores of Yihun Lhatso, you will notice that many of boulders have been dredged from the lake or nearby streams and carved into mani stones, which blend seamlessly into the natural landscape and serve as a testament to this lake’s spiritual reputation. Alongside the carving of mani stones and the placing of multi-coloured prayer flags, many Tibetan monks and laypeople travel to the lake every year on religious pilgrimages. During these pilgrimages, they will take part in what’s known as a kora or pilgrimage circuit, where they walk around the entirety of the lake as a form of meditation and worship. Given the colossal size of natural sites like Yihun Lhatso, these pilgrimage circuits are huge undertakings and can take upwards of weeks or even months to complete!

Make your dream trip to the Huiyuan Monastery come true on our travel:

Guzang Festival

The Guzang Festival has been shrouded in mystery for hundreds of years. It is a traditional festival of the Miao people but unlike other festivals in China, which are usually annual, the Guzang Festival only takes place once every twelve years. Preparations for this unusual festival begin two years before the festivities are due to start and the festival itself can last upwards of 15 days! The name Guzang derives from the two words “gu” and “zang”, which mean “drum” and “to bury” respectively. Thus “guzang” means “to bury the drum” as drums are particularly significant to this festival.

It is sometimes referred to as the Gushe Festival, as it was once a way of bringing together communities of kindred clans known as gushe. Every twelve years a different Miao village will host the festival, although a smaller festival is held every year that lasts only four days. Each year this smaller festival will have a different ritual theme and is sometimes referred to as the “Small Guzang Festival”. Ancient Miao songs indicate that the Guzang Festival was celebrated by early Miao clans during the Xia Dynasty (c. 2100-1600 B.C.), which would make this festival thousands of years old. The festival is particularly important to the Miao because it focuses on commemorating their ancestors, with particularly reference to their shared ancestors and origin story.

Origins of the Guzang Festival

According to Miao legend, the origin of man began with a maple tree called the White Maple. After being struck down, this mystical tree went through a transformation. Its roots turned into fish, its trunk turned into a copper drum, its branches became a bird, and its core, or spiritual essence, manifested as a butterfly. This butterfly fell in love with and became pregnant by the foams of the waves.

She laid 12 eggs, which were hatched by the legendary bird Ziyu that had been born out of the White Maple. The eggs took 12 days and 12 nights to hatch. Out of these eggs were born the thunder god, the dragon, the ox, the tiger, the elephant, the snake, the centipede, a human boy, and his sister. Thereafter the butterfly was known as Mother Butterfly or Butterfly Mother. The boy, Jiangyang, and his sister are considered to be the first human beings on earth, so in Miao folklore Mother Butterfly is the equivalent of God in Christianity. She features prominently in Miao craftwork. The celebrations of the Guzang Festival are all based around some facet of this origin story.

Burying the Drum

Two different kinds of drum will be used during the festival: the double drum and the single drum. The double drum is made up of two single drums and is massive, averaging 170 centimetres in length and 30 centimetres in diameter. Before the festival, the double drums are usually kept in the house of a couple who is married but childless. The Miao believe that the presence of the double drum will help the couple conceive a child.

The single drum is substantially smaller than the double drum and a new one will be made for each festival. When the festival ends, this single drum will be placed in a cave, where it will be left to decay. This “burying” of the drum is where the festival derives its name. In July, before the next Guzang Festival, the hosting village will retrieve this old single drum as part of a ceremony known as Xinggu or “Awakening the Drum”. This takes place a year before the festivities begin. The hosting village will then make the new single drum.

The drums are crafted using maple wood, with cowhide covering both ends of each drum. Since the maple tree is revered by the Miao people as the origin of life, the Miao believe that the souls of their ancestors live inside these huge drums. They beat the drums loudly under maple trees in order to wake up their ancestors, who they believe will take part in the festival.

Festivities

Two years before the festival is supposed to take place, a leader will be chosen to begin the ceremonies and an organising committee will be formed. Usually the leader is an elderly married man from the community. During the festivities, this leader will wear a violet shirt and will sometimes have dried fish attached to his headdress. These fish symbolise the Miao’s belief that their ancestors used to live along the Yangtze River and sustained themselves by fishing.

As aforementioned, in July of the first year there is the “Awakening of the Drum” ceremony. A team is formed, made up of a priest, leaders from every village, and representatives from each clan. Together, they will go to the Drum Temple on the mountain to retrieve the old single drum. A mallard is sacrificed and its blood is sprinkled around the holy drum. The priest will then chant using special language in order to “wake up the drum”.

In October of the second year, there is a “Welcoming the Drum” ceremony. The same team from the first year assemble and welcome the holy drum into the village. Villagers will play the lusheng and dance to celebrate the coming of the drum.

During April of the third year, the leader is responsible for choosing the sacred bulls that will be sacrificed during the festivities. Once these bulls have been selected, they are fed well and must not be used for any kind of farm work. This ceremony is called Shenniu or “Inspecting the Cattle”. Not long after the cattle have been chosen, the leader will go to the previous hosting village to retrieve their single drum, as aforementioned.

After these two years have passed and the preparations are complete, the festival will begin. Throughout the fifteen days of the festival, bullfighting will take place between the sacred bulls and the Miao people are permitted to eat meat and bean curd but not vegetables of any kind. The first day of the festival is just a simple opening ceremony.

On the second day of the festival, the leader of the festival will travel into the mountains with a shaman in search of the soul of the dragon, which is a symbol of good luck. The shaman will carry a male duck around the mountain and guide the soul of the dragon into the duck in a ceremony known as Zhaolong or “Inviting the Dragon”. In the evening, a pig will be sacrificed and all of the participants will share the meat in a celebratory feast. Families will get together with friends and relatives from other villages to have their own feasts and these celebrations will go on late into the night. The sharing of the meat represents the union of the community, the harmonious relationships of the villagers and the preservation of ancient traditions. Good relations between families, distant relatives and members of other villages are integral to the survival of Miao culture.

On the third day, a large bronze drum will be hung from a green bough in the centre of the courtyard. This drum symbolises life and fertility. The shaman and the organising committee will form a circle around the drum and beat it, while being accompanied by men playing the lusheng. Young girls from surrounding villages will deck themselves out in traditional dress and dance around the drum. By the late afternoon, a huge circle of dancers will form. Newcomers will be welcomed to the festivities with liquor or “horn spirit” served from a bull’s horn. This dancing ceremony can last upwards of 4 to 6 hours.

Once the dancing has finished, the shaman will light incense, burn paper money and chant as part of an offering to the ancestors. Then there will be another feast in the village, and the organising committee will settle down to eat and discuss the festival. After the feast, an entertainment troupe from another village will be invited to perform. They will dance and sing Miao folk songs while the young people watch. On the afternoon of the fourth day, the drum will sound again, signifying the start of another dancing ceremony. In the evening, the shaman will end this dancing ceremony by making more offerings.

On the fifth day of the festival, the sacrificial bulls will be adorned with decorations and paraded around the village, with locals setting off firecrackers in their wake. On the dawn of the sixth day, the bulls will be sacrificed and their heads will be placed together facing east, which symbolises the belief that the Miao ancestors came from east China. A ceremony is held to release the souls of the bulls from purgatory and then villagers will sing ancient sacrificial songs. The meat from the bulls will be divided among the village households so they can all hold their own feasts.

Unfortunately, due to the bullfighting and the sacrifices, many bulls will die during this festival. Any bull that dies during the bull fights is commemorated as a hero and given a proper burial. His bravery will be recounted on his tombstone. In order to keep the mood light, the Miao will use euphemisms to describe any unsavoury event. For example, “kissing the big official” means butchering a pig, “give me the leaf” means “give me the butcher’s knife”, and “use the quilt to cover the official” stands for feeding straw into the stove fire in order to cook the pork.

The Guzang Festival reflects the Miao’s social values, with an emphasis on community, ancestor worship, hard work, piousness, peace and happiness. It is a truly magnificent spectacle and its rarity makes it even more enticing. Outsiders can participate in all of the festivities except for the Ancestor Worshipping Ceremony, so if you’re planning a trip to Guizhou and the Guzang Festival is approaching, we urge you to grasp this once in a lifetime opportunity.

Join a travel with us to experience the Guzang Festival with Miao People: Explore the culture of Ethnic minorities in Southeast Guizhou

The Palcho Monastery

Nestled within a river valley in the town of Gyantse in Shigatse Prefecture, Tibet, the Palcho Monastery represents an unusual intermingling of faiths. Sometimes referred to as the Pelkor Chode Monastery, this venerable place of worship is one of the only monasteries that incorporates teachings from multiple sects of Tibetan Buddhism. Within its walls, you’ll find artwork and scriptures dedicated to the Sakya, Gelug, and Kagyu sects of Tibetan Buddhism.

The main temple of the monastery complex is known as Tsuklakhang and was built sometime between 1418 and 1425. This three-storey building follows the typical Tibetan style of architecture. The ground floor has been divided into three parts: the front hall, the main hall and the back hall. There is a Dharmapāla[1] chapel on the right side of the front hall and a Buddha chapel on its left side. The main hall is where the monks study and chant, and is supported by a sequence of 48 colossal pillars.

Within this hall, there is a spectacular 8-metre-tall bronze statue of the Buddha that is the main subject of worship. Like the front hall, there are also two small chapels on either side of the main hall. The back hall, by contrast, is much smaller and is only supported by 8 pillars. It also contains a bronze statue of Buddha as its main subject of worship. There are another 5 chapels on the first floor and one large chapel on the top floor, which is home to a series of breathtakingly beautiful murals. Once the temple was originally completed, it became an important monastery for the Sakya sect of Tibetan Buddhism.

In 1427, the Tibetan noble Rabten Kunzang Phak donated vast sums of money in order to expand the monastery, which led to the addition of what’s known as a Kumbum[2] and a few other buildings. This colossal construction project was led by a monk named Khedrup Je, who was posthumously recognised as the first Panchen Lama. The Kumbum at the Palcho Monastery rose to become not only the most prominent of its kind in Gyatse, but also the most famous Kumbum in Tibet. This particular Kumbum is made up of a staggering ten storeys. From the first floor to the ninth floor, you will find 76 chapels with 108 doors. Each chapel contains a variety of stunning Buddhist statues. You can recognize the artistic value of each and every statue simply by looking at the vivid facial expressions of the figures being portrayed. Thanks to this expansive statue collection, this Kumbum is sometimes referred to as the “Hundred Thousand Buddha Stupa.”

Alongside the statues, the murals are another invaluable and celebrated artistic asset of the Palcho Monastery. They can be found throughout every chapel of the Kumbum and in every room of the main temple. The murals in the main temple were painted following a deliberate and carefully planned design, which was based around the function of the hall and who would typically be worshipping within it. For example, in the main hall you will find the three main Buddhas associated with Buddhism: Gautama Buddha, Dīpankara Buddha[3] and Maitreya Buddha [4]. The murals in the Kumbum are mainly dedicated to depicting stories from the Vajrayāna sect of Buddhism [5].

Throughout its long history, the Palcho Monastery has suffered through three major catastrophes. In 1904, a British expedition decided to infiltrate Lhasa via Gyantse. After about 100 days of warfare, the people of Gyantse were unable to prevent this invasion. The British expedition therefore captured Gyantse and decided to make the Palcho Monastery their temporary military base, which caused a huge amount of damage to the interior. The second catastrophe that caused colossal damage to the monastery happened during the 1959 Tibetan Uprising, the event which prompted the 14th Dalai Lama to flee to India. The final catastrophe came only ten years later, when the monastery was ransacked during the Cultural Revolution.

Fortunately, the entire monastery has been restored and the restoration project did a wonderful job of repairing the damage. Nowadays, when you visit the monastery, you will still be struck by its vibrancy and beauty. You may find, however, that the colour on some of the murals has changed due to the burning of the ceremonial butter lamps. This is not a scar left by historical atrocities, but is simply a mark of time and religious devotion.

[1] A Dharmapāla is a type of wrathful god in Buddhism.

[2] A Kumbum is a multi-storied stūpa of Buddhist chapels in Tibetan Buddhism.

[3] Dīpankara is one of the Buddhas of the past.

[4] Maitreya is regarded as the future Buddha.

[5] The term Vajrayāna is used to refer to one of the major sects of Buddhism, which is sometimes known as the Tantric sect. It mainly focuses on the chanting of mantras, the use of special gestures known as mudras, and visualization methods with the help of paintings called mandalas.

Make your dream trip to the Palcho Monastery come true on our travel: Explore Untouched Wilderness on Our Full Circuit of Tibet

The Tagong Monastery

In 641 AD, the Han Chinese Princess Wencheng of the Tang Dynasty (618-907) made the long journey to Tibet in order to marry Songtsän Gampo, the founder of the Tibetan Empire (618–842). Emperor Taizong of the Tang Dynasty gave her a statue of Shakyamuni[1] Buddha as her dowry. That being said, this was no normal statue! It was a 1.5-metre (5 ft.) tall life-sized depiction of the historical Buddha at the age of 12, which is known as the Jowo Shakyamuni or the Jowo Rinpoche. The statue was supposedly carved at the behest of the Buddha himself.

When the princess and her retinue were traveling past Tagong, something unexpected happened. The statue of the Jowo Shakyamuni refused to move! The princess interpreted this as Buddha’s intention to stay there. There was one major problem with this, however. The statue was meant to be brought to Lhasa and presented to Songtsän Gampo! The princess decided that the only solution would be to make a copy of the statue, which would be left at Tagong. Once the new statue had been completed, the original statue was finally able to be moved again and continued on its journey. Later on, Songtsän Gampo issued an order for 108 Buddhist temples to be built that would face the Tang Empire. The Tagong Monastery, which contains the copy of the Jowo Shakyamuni statue, was the 108th temple to be built. You can find the original statue in the Jokhang Temple of Lhasa.

Located in the Garzê Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture of Sichuan Province, near to the side of the Sichuan–Tibet road, the Tagong Monastery belongs to the Sakya sect of Tibetan Buddhism. The term “tagong” means “the bodhisattva is glad” in the Tibetan language. The temple complex itself includes the Mahavira Hall or the Main Hall, the Jowo Shakyamuni Hall, the Dharmapāla[2] Hall, the Thousand-Hand Avalokiteśvara Hall, three other lesser halls, the pagoda forest, and the dormitories of the monks. There are nearly 200 prayer wheels that can be found throughout the monastery as well.

Like other monasteries, the Mahavira Hall within the Tagong Monastery is the place where monks learn Buddhist scripture and chant. The murals in this hall have been preserved in their original condition for over 300 years. Within these gorgeous murals, you will find images of Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, the “Five Venerable Supreme Masters” of the Sakya sect, and stories of famous Buddhist monks.

As the name suggests, the Jowo Shakyamuni Hall houses the legendary statue of Jowo Shakyamuni, which is decorated with colourful gems. Within this hall, there is also a statue known as the Thousand-Hand Avalokiteśvara, which was also sculpted under the instruction of Princess Wencheng. Locals and pilgrims believe that this statue is so sacred that it has certain magical powers.

Another legendary sacred relic within this hall is the supposed footprint of Drogön Chogyal Phagpa, who was one of the “Five Venerable Supreme Masters” of the Sakya sect and the fifth Sakya Trizin [3]. He reputedly left this footprint when he visited the monastery sometime during the 13th century.

The Thousand-Hand Avalokiteśvara Hall is relatively new compared to the rest of the complex, as it was only built in 1997. It houses the tallest bronze statue of the Thousand-Hand Avalokiteśvara in the entire Tibetan area.

Behind the Tagong Monastery is the holy Mount Yala. This snow-capped peak shines under the cloudless blue skies of the plateau. For hundreds of years, numerous monks have traveled to the mountain and practiced their faith on the remote mountainsides. According to legend, there are warm springs dotted throughout the Mount Yala area that can clean any hopeful Buddhist monk of their impurities.

[1] Shakyamuni: One of the titles of Gautama Buddha, the central figure and founder of the Buddhist faith. It is derived from the place named Sakya, which is where he was born.

[2] A Dharmapāla is a type of wrathful god in Buddhism.

[3] Sakya Trizin is the traditional title of the head of the Sakya school of Tibetan Buddhism.

Make your dream trip to the Tagong Monastery come true on our travel:

The Huiyuan Monastery

At the beginning of the 18th century, Tibet was in turmoil as two powerful political groups became embroiled in the search for the next Dalai Lama. One group was led by a man named Lha-bzang Khan, who was the ruler of the Khoshut Khanate [1]. The leader of the opposing faction was known as Desi Sangye Gyatso and was widely regarded as the most powerful man in Tibet, particularly since he had been the regent of the 5th Dalai Lama. ON top of all of this internal political power, Desi Sangye Gyatso also had a good relationship with the Dzungar Khanate [2]. The conflict only ended because Desi Sangye Gyatso was murdered. It seems Lha-bzang Khan would not escape so lightly either, as the Dzungar Khanate invaded Tibet in 1717 and he was killed in the ensuing chaos.

The invasion subsequently quashed by an expedition sent by the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912 AD), which was the ruling regime of China at the time. This Qing military expedition expelled the Dzungars from Tibet in 1720. In 1721, they enthroned Kelzang Gyatso as the seventh Dalai Lama in a ceremony at the Potala Palace.

In spite of this outward calm, however, secret dissent and popular discontent was increasing during the new Tibetan cabinet era. This eventually led to the assassination of the leader and chaos reigned once again. The new ruling leader, a man named Polhané Sönam Topgyé, decided to take revenge on those who were responsible for the assassination. In a shocking twist, it was believed that the father of the seventh Dalai Lama had been involved in planning the assassination!

From here onwards, the story seems to diverge, as there are two different versions of what may have happened next. The seventh Dalai Lama was either summoned to Beijing by the Qing government but was stopped in Litang by Polhané Sönam Topgyé, or he was ordered to go to Litang, which was his birth place.

Regardless of the reasoning behind it, the seventh Dalai Lama Kelzang Gyatso was sent to Litang, where the Huiyuan Monastery was built for him. Meanwhile, the 5th Panchen Lama was called to Lhasa by the Qing emperor Yongzheng in order to take control of certain areas within the ancient region of Tibet. From then on, the Panchen Lama’s power was used to balance out the power of the Dalai Lama.

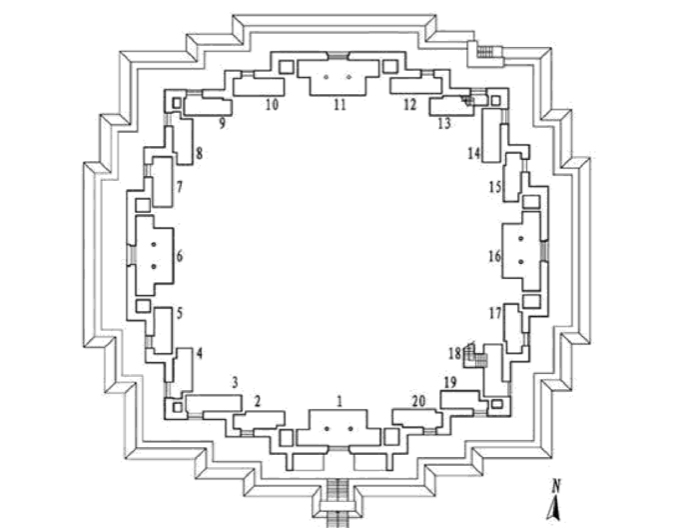

When you are standing in front of the Huiyuan Monastery, you may be surprised to find that such an isolated monastery with such a simple appearance is related to some of the most influential moments in Tibetan history. The Huiyuan Monastery belongs to the Gelug sect of Tibetan Buddhism and, in terms of its architecture, it follows the typical Tibetan Buddhist monastery style. You may get the feeling that the Huiyuan Monastery is a simplified version of the Drepung Monastery, but it incorporates some royal architectural features.

The monastery is located in the county of Daofu within the Garzê Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture. The entire complex covers a colossal area of around 83 acres and contains more than one thousand rooms. According to a typical monastery’s layout, the main structures are the Buddha Hall, the studying area for the monks, and the monks’ dormitories. Alongside these main structures, the Huiyuan monastery has something extra special, the steles pavilion, which is home to five steles that date back to the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911).

The 7th Dalai Lama Kelzang Gyatso lived within the Huiyuan Monastery for seven years. In 1735, the Yongzheng Emperor sent his own brother, Prince Guo, to help Kelzang Gyatso return to Lhasa. During his time at the monastery, Prince Guo wrote a long poem that described the local life and culture, which was made into a stele. However, it was destroyed during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976).

The significance of the Huiyuan Monastery didn’t end up when Kelzang Gyatso left. Over one hundred years later, fate would shine on the monastery yet again, as the 11th Dalai Lama Khedrup Gyatso was born near the Huiyuan Monastery. In response to this fortuitous event, the Qing court bestowed an honour known as the “Nine Dragons and Nine Lions” on the monastery. “Nine Dragons” refers to the Qing court, while “Nine Lions” represents the Kashag [3]of Tibet. Visitors can find the “Nine Dragons and Nine Lions” on the wall outside of the main hall.

During its long and venerable history, the Huiyuan Monastery was supported directly by the royal family of the Qing Dynasty. The buildings and Buddhist art in the monastery, however, were tragically damaged during the Cultural Revolution. In 1982, the government provided grants to the complex so that they could be repaired.

Every year, from the 1st to the 7th of June according to the Tibetan Calendar, a prayer ceremony and other religious activities are held in the Huiyuan Temple. Collectively, these festivities are known as the Mask Dance Festival.

On the first day, the monks who inhabit the temple will dance in gorgeously decorative dress, but without their iconic masks. The next day is dedicated entirely to the prayer ceremony, where worshippers pray for blessings and a brighter future. On the third day, the local people and monks will burn incense and make sacrifices to the gods in the hopes that their homes will be protected from future disasters. On the fourth day, the monks don their traditional dress again, along with their iconic masks, and perform the mask dance, which is known as the Cham Dance. From the 5th through to the final 7th day, there are horse racing events and other folk activities.

1) The Khoshut Khanate was a kingdom located on Tibetan Plateau, which ruled the area from 1642 to 1717.

2) The Dzungar Khanate (1634-1755) was an Inner Asian khanate ruled by the Oirat Mongolians.

3) The Kashag was the governing council of Tibet from 1721 right through until the 1950s.

Make your dream trip to the Huiyuan Monastery come true on our travel: