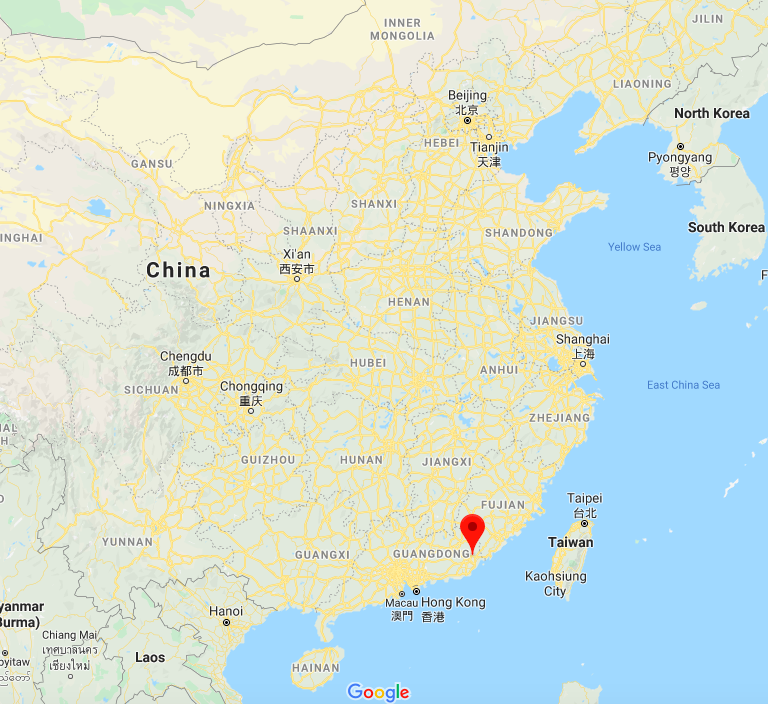

In China, there is an old saying which states: “Wherever people from Chaozhou live, you’ll find Gongfu Tea.” While the art of Gongfu Tea or “Kung-Fu Tea” is popular throughout China, it is widely believed to have originated from the city of Chaozhou in Guangdong province. To this day, most families in Chaozhou will have a special tea table in their home and a traditional tea set that is specifically designed for serving Gongfu Tea. Now you’re probably thinking: What’s so tea-rrific about Gongfu Tea?

This style of tea, which has been popular among the locals of Chaozhou since the Song Dynasty (960-1279), is known for its formidably strong and bitter flavour, earning it the nickname the “espresso of Chinese teas.” Traditionally Gongfu Tea is served before and after a meal in most restaurants throughout Chaozhou, but it can also be savoured on its own in one of the city’s many teahouses. The term “gongfu” or “kung-fu” does not refer to any tea-related martial arts, and instead is used to mean “making tea with skill.” This term extends even further, as the art of tasting the tea is similarly believed to require a certain level of skill. There’s no time to relax when it comes to this cup of afternoon tea!

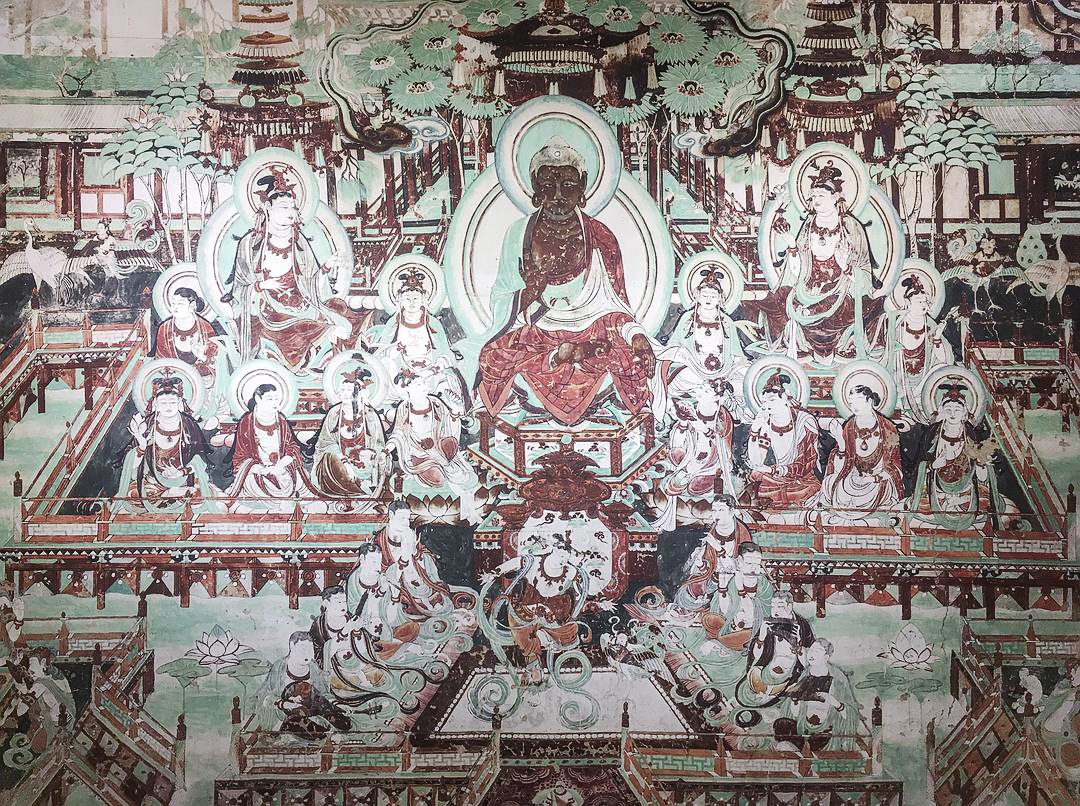

Gongfu Tea is not a type of tea specifically, but is in fact a style of tea ceremony that involves the ritual preparation and presentation of tea. Nowadays, this method of making tea is popular throughout Chinese tea shops and is used by tea connoisseurs worldwide in order to maximize their tea drinking experience. For lovers of Gongfu Tea, it is as much about self-cultivation as it is about the preparation of the tea itself. By focusing on the movements of the tea ceremony, as well as the taste, aroma, and appearance of the tea, the practitioner of Gongfu Tea will become aware of what is known as the “cha qi” (茶气) or “tea energy” and will thus gain greater insight into how the tea affects both their body and mind.

When it comes to the tea ceremony itself, black teas such as oolong and pu’er are preferred. White and green teas can also be used, but their delicate flavour means there is little benefit to brewing them in this way. It is also imperative to use the best grade of tea possible, as good quality tea will yield between 6 to 10 brews with consistent flavour. Lower quality tea may have a pleasant taste for the first couple of brews, but its flavour will significantly weaken thereafter, meaning you’ll have to use more tea leaves in the long run.

In essence, the purpose of Gongfu Tea is to utilize the best materials, instruments, and methods to brew the tea in order to get the maximum flavour and maximum number of brews out of the tea leaves themselves. Its thoroughly practical nature means it is distinctly different from the well-known Japanese tea ceremony known as Chanoyu, where the focus is on the symbolic meaning behind each step rather than on its functional purpose. The history behind these two tea ceremonies, however, is delicately intertwined.

During the 12th century, Japan began growing and producing tea following Chinese models. Towards the end of the 14th century, loose leaf tea became a popular household product in China and it was eventually used by the imperial government during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644). Once the status of loose leaf tea was raised, related teaware such as the teapot became an essential item. More attention was thus being paid to the act of brewing tea, which resulted in the Gongfu Tea ceremony becoming popularised sometime during the 18th century. This had a major impact on tea-drinking culture in Japan and their tea ceremony began taking shape almost simultaneously.

Arguably, the most important instrument for making Gongfu Tea is the teapot. The best teapots are unglazed clay teapots made from special “Yixing clay” from the county of Yixing in China’s Jiangsu province. This clay comes in three types that influence the colour of the teapot: purple, red, and green. The porous nature of these teapots and their heat handling properties mean they are superior to glass, porcelain, and glazed teapots. The main downside, however, is that one teapot should only be used to brew one type of tea and Yixing teapots are generally quite expensive. Over time, the Yixing teapot will absorb the flavour of the tea and thus enhance the tea-drinking experience. High-fired teapots with thinner and finer clay work best with green, white, and oolong teas, while low-fired teapots with thicker and more porous clay should be used for pu’er and black teas.

When it comes to the brewing of the tea itself, there are two essential factors that need to be considered: the water being used; and the temperature the water is boiled at. It should come as no surprise that water which tastes or smells bad will not yield a pleasant tasting tea. However, distilled or extremely soft water can be equally unpleasant, as it lacks minerals and can results in a “flat” or flavourless brew. That being said, high content mineral water should similarly be avoided, as it can overwhelm the flavour of the tea. Local and natural spring water is ideal, although bottled spring water will suffice.

When it comes to boiling the water, the optimal temperature varies between different types of tea. For example, water used to brew oolong tea should be heated to 95 °C (203 ℉), while water used to brew compressed teas such as pu’er should be boiled at 100 °C (212 ℉). Most tea masters don’t need to use a thermometer and can accurately gauge the temperature of the water based on both the timing and the air bubbles in the kettle. According to Chinese tradition, the bubbles formed at between 75 to 85 °C (167-185 ℉) are known as “crab eyes” due to their size and are typically accompanied by loud, rapid sizzling noises. At 90 to 95 °C (194-203 ℉), the bubbles are called “fish eyes” because they are much larger and they are accompanied by a slower, quieter sizzling noise. Once the water has reached boiling point, there should be no visible air bubbles and no discernible sizzling sounds.

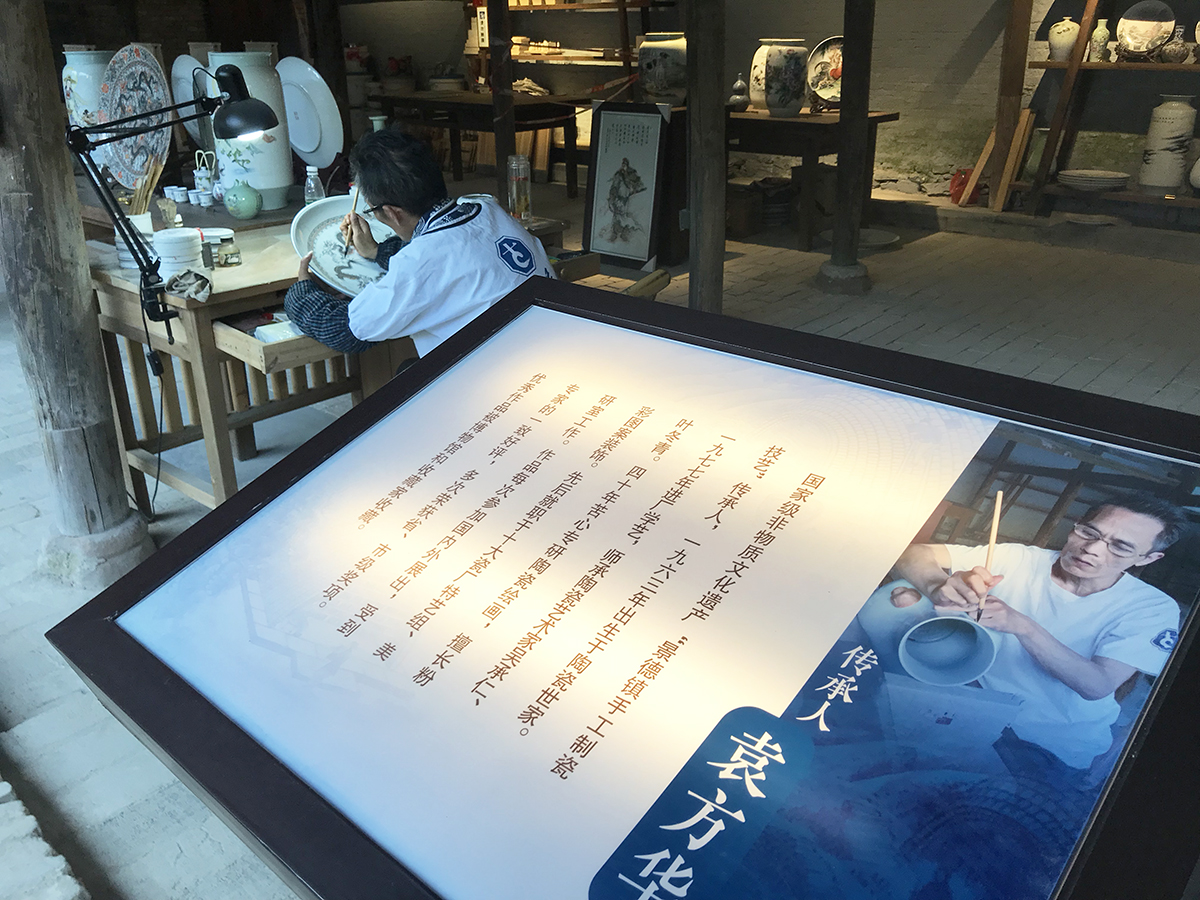

The complexity of the ceremony means that any tea master must be equipped with an arsenal of instruments at their disposal! The main instruments used in Gongfu Tea are: the teapot or a covered bowl known as a gaiwan; the tea pitcher or decanting vessel, which is used to ensure the flavour of the tea is consistent when its poured into multiple cups; the kettle; the brewing tray, which is specially designed to hold spills; a tea cloth; a tea spoon or tea pick, which is used to clear excess tea from the spout of the teapot; the timer; the tea strainer; a special type of wooden tea spoon that is used to measure the correct amount of tea leaves required; and tea cups, preferably three that are of matching size and style.

If that wasn’t complicated enough, there are also several optional instruments that are believed to enhance the tea-drinking experience. These are: the tea basin, which serves as a receptacle for used tea leaves; a set of scales to weigh the tea leaves; a scent cup, which is solely used to appreciate the tea’s aroma and is never drank from; a pair of tongs known as “jia” (挟) that are used to pick up and empty the tea cups; and a calligraphy-style tea brush, which can be used to spread the wasted tea across the tea tray and ensure that the tea soaks into the tray evenly, endowing it with a pleasant colour.

While all of these instruments are considered necessary for the proper preparation of Gongfu Tea, there is one addition to the ceremony that is purely aesthetic. Most tea shops and tea masters will have at least one “tea pet,” which is a small statue that is typically made from the same unglazed clay as a Yixing teapot. The use of tea pets dates all the way back to the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368) and they are often modelled after classical Chinese figures, such as the dragon, the zodiac animals, the lion turtle, and the toad. Each tea pet will have a special symbolic meaning and they are believed to bring good luck to their owners. The first brew of the tea and any leftover tea is poured over the tea pet as an offering, but it has the added benefit of preventing the water from splattering on the tea tray. After all, the last thing you want during a leisurely tea ceremony is to end up in the splash zone!

Finally, you’re probably wondering: What actually happens during Gongfu Tea? First, the teapot is filled with boiling water and allowed to sit until it has become warm. The boiling water is then poured over the strainer and the tea cups in order to sterilize them. Once the teapot is emptied, the tea leaves are measured and placed into the teapot. Boiled water is then added to the teapot until it is overflowing and, after the lid has been placed back on, this water is immediately poured off either onto the tea tray or the tea pet. This process is believed to “wake up” the tea leaves in preparation for the second brew.

After that, the water is heated to the requisite temperature, added to the teapot, and left for few seconds. Warm water should be poured over the teapot while the tea is brewing, in order to maintain an even brewing temperature. Once the tea is finished brewing, it is poured into the tea pitcher or decanter and the lid is placed on top. The teacups should now be emptied of the warm water used to sterilize them, preferably with a pair of tongs. When the teacups are empty, the tea can be served from the pitcher. Ideally the tea cups should be placed close together and filled continuously in a circle, so that the strength of the tea is the same in each cup.

Multiple brews can be yielded by simply repeating the process of adding water to the teapot. When the process is finished, the leaves are removed and the teapot should be rinsed with hot water before being allowed to air-dry. In order to ensure that all of the instruments remain clean, they should also be rinsed and allowed to air-dry.

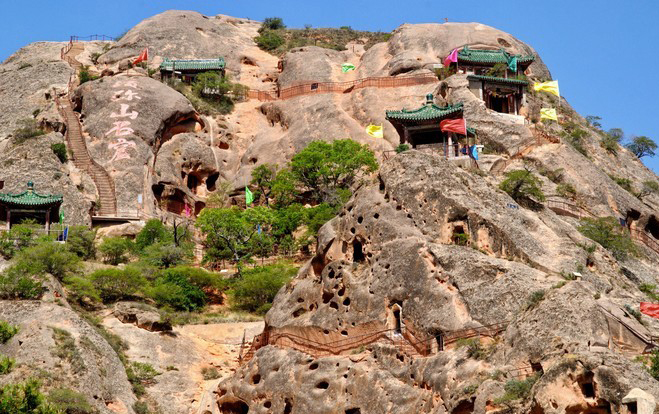

Try cups of Gongfu Tea on our travel: Explore the Ancient Fortresses of Southeast China