Fenghuang Ancient Town

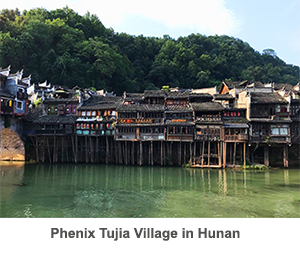

The rural county of Fenghuang can be roughly split into two districts: New Town and Old Town. While the new town is simply a residential area, the old town is something altogether more enchanting. Fenghuang Ancient Town was officially established during the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912), but its history can be traced back as far as the Spring and Autumn Period (c. 771-476 B.C.). Rising at the base of misty mountains and facing the rippling Tuo River, its location is known for its excellent feng shui 1.

The name “Fenghuang” literally translates to mean “Phoenix”, which in Chinese tradition is associated with good fortune and longevity. According to local legend, the town is so-named because, one day, two phoenixes were flying overhead when they paused to admire the town’s beauty and were reluctant to leave. If it’s enough to catch the attention of a mythical creature, it must be one magical place! For over 300 years, the ancient streets, alleyways, and houses of Fenghuang have been exquisitely preserved.

Its most unique feature is undoubtedly its wooden diaojiaolou 2, which perch delicately over the river. The incorporation of the river into the town’s layout demonstrates how important it is to the villagers to live in harmony with nature. It is not uncommon to see women washing clothes or men casting their fishing nets into its expanse, much like they have done for centuries. Boatmen wait by the banks, offering visitors the chance to enjoy a scenic cruise up and down the river.

Its most unique feature is undoubtedly its wooden diaojiaolou 2, which perch delicately over the river. The incorporation of the river into the town’s layout demonstrates how important it is to the villagers to live in harmony with nature. It is not uncommon to see women washing clothes or men casting their fishing nets into its expanse, much like they have done for centuries. Boatmen wait by the banks, offering visitors the chance to enjoy a scenic cruise up and down the river.

The diaojiaolou are also the first hint towards the town’s multi-ethnicity. Unlike other cities and towns in China, which are predominantly populated by the Han Chinese ethnic group, the vast majority of Fenghuang’s population is made up of Miao and Tujia people. Miao traditions, architecture, and culture dominate the town, from their elegant traditional dress to their intricate handicrafts. Shimmering silver jewellery, vibrant batik 3 cloth, homemade tie-dye clothes, and numerous other local specialities are sold in Fenghuang’s local shops.

Yet the Miao weren’t always the peaceful villagers that you see today! Fenghuang was once the centre of numerous Miao rebellions, which were so fierce that it prompted the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) to build the Southern Great Wall. This wall still stands on the outskirts of the town, and is now a popular tourist attraction. Other local attractions of note include: Huang Si Qiao Castle, one of the most well-preserved castles from the Tang Dynasty (618-907); Longevity Palace; Chao Yang Palace; and the Heavenly King Temple.

The former residence and tomb of the renowned Chinese writer Shen Congwen is arguably the most popular site in the town. In fact, his novel The Border Town, a romance written in 1934 and set in Fenghuang County, is believed to be what catapulted Fenghuang Ancient Town to national fame. It appears that Fenghuang’s residents were truly blessed with good fortune, as it was also the hometown of Xiong Xiling, who was once the premier (1913-1914) of the Republic of China (1912-1949) , and Huang Yongyu, a celebrated painter in the traditional Chinese style.

The former residence and tomb of the renowned Chinese writer Shen Congwen is arguably the most popular site in the town. In fact, his novel The Border Town, a romance written in 1934 and set in Fenghuang County, is believed to be what catapulted Fenghuang Ancient Town to national fame. It appears that Fenghuang’s residents were truly blessed with good fortune, as it was also the hometown of Xiong Xiling, who was once the premier (1913-1914) of the Republic of China (1912-1949) , and Huang Yongyu, a celebrated painter in the traditional Chinese style.

The playful bubbling of the river; the feel of flagstone steps worn smooth by thousands of feet; the sweet smell of freshly cooked food, dotted with locally grown chillies as red as rubies; these are the simple pleasures that this picturesque town has to offer. Surrounded by primeval forests and flanked by shadowy mountains, it is a place lost in time and resplendent in its timelessness.

1. Feng Shui: This theory is based on the premise that the specific placement of certain buildings or objects will bring good luck.

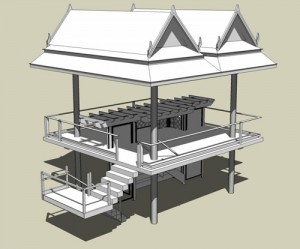

2. Diaojiaolou: These are two-storey wooden dwellings that are suspended on stilts, with the ground floor being used for storage and the upper floors being used as living spaces.

3. Batik: A cloth-dying process whereby a knife that has been dipped in hot wax is used to draw a pattern onto the cloth. The cloth is then boiled in dye, which melts the wax. Once the wax has melted off, the cloth is removed from the boiling dye. The rest of the cloth will be coloured by the dye but the pattern under the wax will have remained the original colour of the cloth.

Baihaba Village

With titles like “Number One Village of Northwest China” and the “First Village in the Northwest”, there are no prizes for guessing where Baihaba Village might be! It rests on the natural border between China and Kazakhstan, at the very northwesternmost corner of China’s Xinjiang Autonomous Region. Since it is only 3 kilometres (2 mi) from this border, tourists must get permission before travelling to the village. Its location just 31 kilometres (19 mi) west of Kanas Lake makes it a popular stop on any tour of the Kanas region, but this bucolic paradise is more than just a glorified rest-stop! Flanked by the misty Altai Mountains and split by the shimmering Baihaba River, it’s a veritable utopia for nature lovers.

The nearby forests are full of pines, white birches, and poplar trees, meaning the landscape is awash with luscious greens, pearl whites, and deep chestnut browns. Temperatures in this virtually Siberian region regularly plummet to below 0 °C (32 °F) in autumn, yet photographers annually brave the cold to enjoy this most picturesque of seasons. When the leaves turn, the forests are flecked with reds, golds, and yellows that perfectly complement the dark green pines. The village’s characteristic log cabins blend seamlessly into their natural surroundings, with only the faint wisp of smoke from their chimneys indicating that they are still inhabited. No matter what the season, the scenery in Baihaba looks like it has just leapt out of a pastoral oil painting!

Water trickling down from the melted ice-caps of the mountains runs through the village’s centre and forms the Baihaba River, separating the community of Tuvan people on one bank from the Kazakh people on the other. Although they come from distinctly different cultures, these two ethnic groups have shared this fertile land and enjoyed a peaceful rural life for decades. The Tuvans are a Siberian people who have Mongolian, Turkic, and Samoyedic roots, while the Kazakhs are a Turkic people who mainly live throughout Central Asia.

The Tuvan people believe that they are descended from the legendary soldiers who served under Genghis Khan, so many Tuvan homes boast a portrait of the great Mongolian warlord above their fireplace. Similarly, the Kazakh’s trace their ancestry back to several medieval Mongolian tribes, including the Argyns and the Huns, as well as ancient Iranian nomads such as the Sarmatians and the Scythians. Although both groups speak their own language, the Tuvan’s Turkic language has been heavily influenced by and bears great similarity to the Kazakh language. So it seems these two diverse ethnicities have more in common than meets the eye. And they both certainly have impeccable taste when it comes to their choice of location!

Thanks to their relative isolation and remoteness, the villagers have managed to preserve their unique traditions and customs. Their homes are lavishly decorated with hand-embroidered tapestries, which add a smattering of colour to their modest furnishings. They cook their meals over quaint woodstoves and sleep on heated brick beds, living a life of humble simplicity. Although tourism now plays an important part in supplementing their income, many families still rely on hunting and raising animals for their livelihood. Every day, farmers graze their sheep and cattle on the verdant pastures, while women wash vegetables in the river and youths ride their horses deep into the mountain valley.

Some of the locals run horse rental businesses, offering guided tours of the countryside for those visitors adventurous enough to take the reins! A handful of Tuvan families have even opened small hotels or restaurants, where tourists can indulge in a brief taste of their rich culture. And the good news is most Tuvan people greet their guests by giving them snacks! Normally they will receive guests with an array of delicious home-made dairy products, such as yogurt, milk wine, milk tea, and freshly baked cakes. Generally speaking, it is not considered impolite to refuse the food, but some B&Bs will welcome visitors with a Tuvan tradition involving two compulsory bowls of milk tea. The host will pour the first bowl and offer the drinker butter, which they can add to taste. As soon as the first bowl is finished, the host will fill it again. According to local belief, it is this second bowl that will grant the drinker good luck. That is, unless you’re lactose intolerant!

Hemu Village

Nestled within the Altay Mountains of northern Burqin County lies the small and tranquil village of Hemu. It is heralded as one of the six most beautiful villages in China and, once you catch a glimpse of it, you’ll soon see why. As the sun rises over the grasslands and illuminates the bright white birch forests nearby, smoke curls up from the chimneys of the village’s quaint log cabins, marking the beginning of a new day. The hundred or so families who live here will while away these daylight hours by grazing their sheep and cattle on the jade green pastures, washing their vegetables in the shimmering Hemu River, or simply taking a long horse-ride through the misty mountains. In summer, the place is awash with the lushest greens, while in autumn accents of gold, red, and purple fleck the landscape.

This rustic paradise, also known as Horm Village, has been home to the native Tuvan people for over a thousand years. Along with Baihaba Village, it is one of the largest Tuvan villages in China, although it also boasts small communities of Mongolian and Kazakh people. The Tuvans are a Siberian people who have Mongolian, Turkic, and Samoyedic roots. Although tourism has now become an important part of their annual income, many of them continue to make a living by hunting and raising animals. In fact, they farm anything from sheep and cows to yaks and even reindeer! They build their log cabins by hand using wood harvested from the nearby forests, which means the village seamlessly blends in with its natural surroundings. Many of the homes have a portrait of Genghis Khan hanging over their fireplace, as the Tuvans believe that they are descended from the soldiers of his ancient and mighty army. So it goes without saying that you shouldn’t get on their bad side!

That being said, the villagers are well-known for their incredible hospitality and will happily welcome visitors into their humble homes. And what better way to greet guests than with snacks! Normally they will receive guests with an array of delicious home-made dairy products, such as yogurt, milk wine, milk tea, and freshly baked cakes. Generally speaking, it is not considered impolite to refuse the food, but some B&Bs will welcome visitors with a Tuvan tradition involving two compulsory bowls of milk tea. The host will pour the first bowl and offer the drinker butter, which they can add to taste. As soon as the first bowl is finished, the host will fill it again. According to local belief, it is this second bowl that will grant the drinker good luck. That is, unless you’re lactose intolerant!

That being said, the villagers are well-known for their incredible hospitality and will happily welcome visitors into their humble homes. And what better way to greet guests than with snacks! Normally they will receive guests with an array of delicious home-made dairy products, such as yogurt, milk wine, milk tea, and freshly baked cakes. Generally speaking, it is not considered impolite to refuse the food, but some B&Bs will welcome visitors with a Tuvan tradition involving two compulsory bowls of milk tea. The host will pour the first bowl and offer the drinker butter, which they can add to taste. As soon as the first bowl is finished, the host will fill it again. According to local belief, it is this second bowl that will grant the drinker good luck. That is, unless you’re lactose intolerant!

In terms of spiritual belief, the Tuvan are firm followers of both Tibetan Buddhism and a folk religion known as Tengrism. This Central Asian faith borrows features from shamanism[1], animism[2], and ancestor worship, and was once the prevailing religion of the Turks, Mongolians, and Hungarians. The rich tapestry of customs and beliefs that the Tuvan subscribe to can be felt most palpably in their lively religious festivals, so plan your visit carefully if you want to experience one.

The village itself is only 70 kilometres (43 mi) away from Kanas Lake, so it’s a popular stop for tourists on their way to the Kanas Lake Nature Reserve. If you’re a fan of hiking, then there is a short hike that leads to a nearby observation platform, which yields stunning panoramic views of the village and the surrounding countryside. For the more adventurous hikers, we recommend venturing out onto the Hemu Grassland, although we strongly advise that you take a local guide with you as the routes are quite treacherous and the local wild boar can be dangerous if encountered. If you’re lucky, you may even come across a cluster of pearl white yurts. Some of these belong to the local Tuvan people, but others are the temporary homes of the Kazakh ethnic minority. Like the Tuvans, the Kazakhs are exceptionally friendly and will happily welcome visitors into their yurt. Just be sure to ask for permission first!

The village itself is only 70 kilometres (43 mi) away from Kanas Lake, so it’s a popular stop for tourists on their way to the Kanas Lake Nature Reserve. If you’re a fan of hiking, then there is a short hike that leads to a nearby observation platform, which yields stunning panoramic views of the village and the surrounding countryside. For the more adventurous hikers, we recommend venturing out onto the Hemu Grassland, although we strongly advise that you take a local guide with you as the routes are quite treacherous and the local wild boar can be dangerous if encountered. If you’re lucky, you may even come across a cluster of pearl white yurts. Some of these belong to the local Tuvan people, but others are the temporary homes of the Kazakh ethnic minority. Like the Tuvans, the Kazakhs are exceptionally friendly and will happily welcome visitors into their yurt. Just be sure to ask for permission first!

[1] Shamanism: The practice of attempting to reach altered states of consciousness in order to communicate with the spirit world and channel energy from it into the real world. This can only be done by specialist practitioners known as shaman.

[2] Animism: The belief that all non-human entities, including animals, plants, and even inanimate objects, possess a spiritual essence or soul.

Diaojiaolou

According to legend, when the first ancient pioneers set out from northern and central China in the hopes of discovering and populating southern China, they came upon a number of difficulties. In the mountainous forests of south China, they met with fierce beasts, venomous snakes, and a myriad of unpleasant insects. In spite of this adversity, they managed to settle a colony in the south and set fires around the colony in order to deter wild beasts. However, the people continued to be plagued by vicious snakes and deadly scorpions, until one of the tribal leaders, an old, wise and well-respected man, came upon an idea for a building suspended on wooden stilts. The colony built these tall dwellings and soon they were safe from the dangers of the creatures below.

These were the first diaojiaolou, a dwelling popular among several of the ethnic minority communities throughout southern China. The word “diaojiao” (吊脚) in Chinese means “hanging feet” and “lou” (楼) means “building”, so diaojiaolou literally means “hanging feet building”. They are so named because of their unusual appearance. The history of the diaojiaolou stretches back over 500 years and they are widespread throughout Yunnan, Guangxi, Hunan, Guizhou, Hubei, and Sichuan province but differ in appearance depending on the ethnic group who built them.

Diaojiaolou are rectangular or square wooden buildings built in the ganlan–style. A ganlan-style building is any building that is supported by stilts or wood columns. Diaojiaolou are typically two to three storeys high. The upper floors are held up by thick wooden stilts, which give the building an unsteady appearance. These stilts are further reinforced by stone blocks at their base, meaning diaojiaolou are in fact very stable. Even if one column is destroyed or one stone block is removed, the building will still stand firm. These buildings are a masterpiece of ingenious carpentry, as oftentimes they are made using no nails or rivets. The structure and stability of the building depends on groove joints, which hold the wooden beams and columns together perfectly.

Diaojiaolou are rectangular or square wooden buildings built in the ganlan–style. A ganlan-style building is any building that is supported by stilts or wood columns. Diaojiaolou are typically two to three storeys high. The upper floors are held up by thick wooden stilts, which give the building an unsteady appearance. These stilts are further reinforced by stone blocks at their base, meaning diaojiaolou are in fact very stable. Even if one column is destroyed or one stone block is removed, the building will still stand firm. These buildings are a masterpiece of ingenious carpentry, as oftentimes they are made using no nails or rivets. The structure and stability of the building depends on groove joints, which hold the wooden beams and columns together perfectly.

The ground floor is made up primarily of the supporting columns and often does not have any walls. This floor tends to be used as a kind of stable for livestock or as a storage space for firewood and farming equipment. The second and third floors will be used as living spaces, although occasionally the top floor will be used as an extra storage space. The top two floors will have verandas or balconies, which are used to dry clothes. Some diaojiaolou built by wealthier families will have attics or annexes to provide more space.

Although the original legend behind the diaojiaolou may seem farfetched, it touches upon one of its main benefits. The key to its popularity is that, in ancient times, these stilted buildings would provide protection from wild animals, and nowadays they continue to provide protection from venomous snakes and insects that are still prolific throughout China. The cool breeze blowing through the windows of the upper levels acts like a kind of natural air conditioner, meaning these buildings also help prevent humidity-related diseases common in southern China. In the south of China, the level of humidity on the ground during summer is almost unbearable and potentially dangerous, so elevated living spaces are particularly important. These stilted houses are also designed to survive most natural disasters, such as floods and earthquakes.

On top of these safety benefits, diaojiaolou also offer some unique benefits that help improve the quality of life for their inhabitants. Their stilted design means they can be built on mountainsides or across bodies of water, so they were often used to colonise previously uninhabitable areas of China. Since the upper floors are particularly high up, they receive more natural light than the ground floor. In the past, this allowed inhabitants to easily work on their craftwork inside and nowadays, because they are naturally well-lit, many diaojiaolou do not have electrical lighting on their upper floors. These upper floors also act as a vantage point, so farmers have a broad view from which to survey their land.

The Miao, Dong, Zhuang, Yao, Tujia, Bouyei, and Shui ethnic minorities have all incorporated diaojiaolou into their architecture and villages. Although the basic style of each diaojiaolou is the same, there are variations between those of different ethnic minorities.

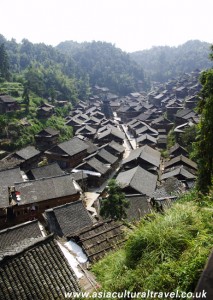

- Miao Diaojiaolou

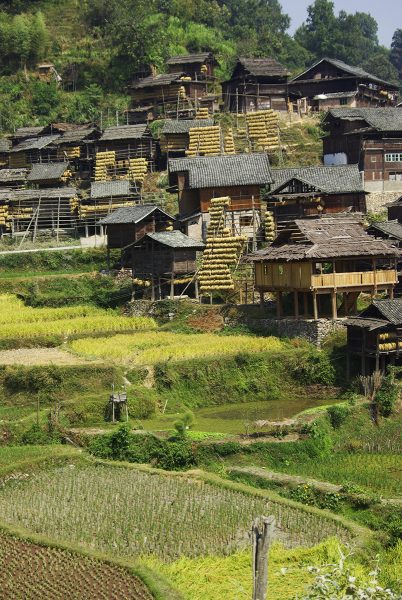

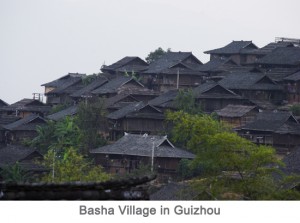

The Miao people have a reputation for living in mountainous areas and thus diaojiaolou make the perfect dwellings. Miao diaojiaolou spread up the sides of mountains and are built on very steep gradients. They are usually built by the villagers using local fir wood. The front of this type of diaojiaolou is held up by pillars but the rear of the house is suspended on wooden poles, making it level with the mountainside. This gives the Miao diaojiaolou their distinctive “hanging” appearance. The Miao villages of Basha, Xijiang and Langdeshang in Guizhou province have particularly stunning diaojiaolou. Xijiang is the largest Miao village in the world and has the widest showcase of Miao diaojiaolou.

The Miao people have a reputation for living in mountainous areas and thus diaojiaolou make the perfect dwellings. Miao diaojiaolou spread up the sides of mountains and are built on very steep gradients. They are usually built by the villagers using local fir wood. The front of this type of diaojiaolou is held up by pillars but the rear of the house is suspended on wooden poles, making it level with the mountainside. This gives the Miao diaojiaolou their distinctive “hanging” appearance. The Miao villages of Basha, Xijiang and Langdeshang in Guizhou province have particularly stunning diaojiaolou. Xijiang is the largest Miao village in the world and has the widest showcase of Miao diaojiaolou.

- Dong Diaojiaolou

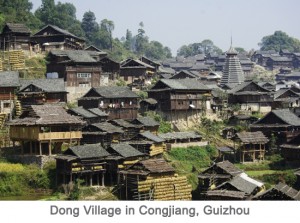

Most Dong villages are at the foot of a mountain or hill and all Dong settlements will be near to a stream or river, so stilted diaojiaolou are useful for building up the mountainside or building over the water. Since the Dong diaojiaolou are not built on a steep gradient, the “hanging” aspect of the upper floors is not as pronounced as it is in Miao diaojiaolou. Dong diaojiaolou are aesthetically magnificent, as the Dong people are skilful carpenters and love to adorn their buildings with intricate carvings of flowers, wild animals and mythical creatures. If you want to see the Dong style of diaojiaolou, we recommend visiting the villages of Zhaoxing and Xiaohuang in Guizhou province. Zhaoxing’s architecture is particularly spectacular, as it contains five Drum Towers of differing styles.

Most Dong villages are at the foot of a mountain or hill and all Dong settlements will be near to a stream or river, so stilted diaojiaolou are useful for building up the mountainside or building over the water. Since the Dong diaojiaolou are not built on a steep gradient, the “hanging” aspect of the upper floors is not as pronounced as it is in Miao diaojiaolou. Dong diaojiaolou are aesthetically magnificent, as the Dong people are skilful carpenters and love to adorn their buildings with intricate carvings of flowers, wild animals and mythical creatures. If you want to see the Dong style of diaojiaolou, we recommend visiting the villages of Zhaoxing and Xiaohuang in Guizhou province. Zhaoxing’s architecture is particularly spectacular, as it contains five Drum Towers of differing styles.

- Zhuang Diaojiaolou

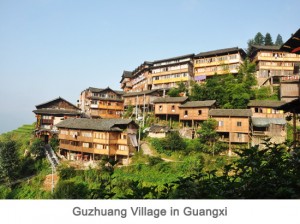

The exterior of the Zhuang diaojiaolou does not look dissimilar to that of the Dong diaojiaolou. However, the key difference is the interior, as they have a shrine at their centre which is used for ancestor worship. They also usually incorporate separate bedrooms for the husband and wife, which is an archaic Zhuang custom. The Zhuang villages of Ping’an and Guzhuang have wonderful diaojiaolou. Guzhuang village has the largest number of Zhuang diaojiaolou in China and some of these buildings date back over 100 years, making them some of the oldest diaojiaolou in the country.

The exterior of the Zhuang diaojiaolou does not look dissimilar to that of the Dong diaojiaolou. However, the key difference is the interior, as they have a shrine at their centre which is used for ancestor worship. They also usually incorporate separate bedrooms for the husband and wife, which is an archaic Zhuang custom. The Zhuang villages of Ping’an and Guzhuang have wonderful diaojiaolou. Guzhuang village has the largest number of Zhuang diaojiaolou in China and some of these buildings date back over 100 years, making them some of the oldest diaojiaolou in the country.

- Yao Diaojiaolou

The Yao ethnic minority tend to live on flat land so Yao diaojiaolou are usually short and have wooden stilts of even heights. In some cases, the ground floor of a Yao diaojiaolou may have walls. The cluster of Yao villages near the Jinkeng Rice Terraces in Guangxi province is the perfect place to admire this style of diaojiaolou. One of these villages, known as Dazhai, even has some diaojiaolou that now function as hotels!

The Yao ethnic minority tend to live on flat land so Yao diaojiaolou are usually short and have wooden stilts of even heights. In some cases, the ground floor of a Yao diaojiaolou may have walls. The cluster of Yao villages near the Jinkeng Rice Terraces in Guangxi province is the perfect place to admire this style of diaojiaolou. One of these villages, known as Dazhai, even has some diaojiaolou that now function as hotels!

- Tujia Diaojiaolou

In contrast to the Miao people, the Tujia people prefer to live near mountains but close to or sometimes even over rivers or streams. Thus you’ll find that many Tujia diaojiaolou are either placed directly on the waterfront or hang over the water. The Tujia believe that these stilted houses embody the coexistence of God and man, so the designs of their diaojiaolou often reflect this. Tujia diaojiaolou are hard to come by, since the Tujia people are slowly abandoning their old settlements and assimilating into modern Chinese culture. The Tujia Folk Customs Park in Zhangjiajie, Hunan, is a large scale replica of a traditional Tujia village and features Tujia style Diaojiaolou. However, if you want a more authentic experience, we recommend visiting the Tujia village of Shuitianba in the Enshi Tujia and Miao Autonomous Prefecture of Hubei Province.

In contrast to the Miao people, the Tujia people prefer to live near mountains but close to or sometimes even over rivers or streams. Thus you’ll find that many Tujia diaojiaolou are either placed directly on the waterfront or hang over the water. The Tujia believe that these stilted houses embody the coexistence of God and man, so the designs of their diaojiaolou often reflect this. Tujia diaojiaolou are hard to come by, since the Tujia people are slowly abandoning their old settlements and assimilating into modern Chinese culture. The Tujia Folk Customs Park in Zhangjiajie, Hunan, is a large scale replica of a traditional Tujia village and features Tujia style Diaojiaolou. However, if you want a more authentic experience, we recommend visiting the Tujia village of Shuitianba in the Enshi Tujia and Miao Autonomous Prefecture of Hubei Province.

- Bouyei Diaojiaolou

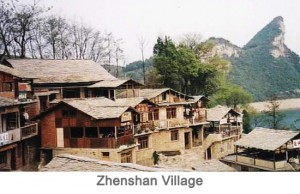

The Bouyei people are renowned more for their unique stone houses than for their diaojiaolou. Their diaojiaolou, though no less magnificent, are relatively typical and have few distinguishing features. The fame of the Bouyei stone buildings has tragically overshadowed their diaojiaolou and thus Bouyei diaojiaolou are difficult to find. Located about 21 kilometres away from the city of Guiyang, Zhenshan village in Guizhou province has a mixed community of Bouyei and Miao people, with Bouyei making up about 75% of its population. Though most of the buildings in Zhenshan are made of stone, a few are made of both wood and stone in the diaojiaolou style. Alternatively, some of the Bouyei villages near the Nanpan River in Yunnan province contain several diaojiaolou.

The Bouyei people are renowned more for their unique stone houses than for their diaojiaolou. Their diaojiaolou, though no less magnificent, are relatively typical and have few distinguishing features. The fame of the Bouyei stone buildings has tragically overshadowed their diaojiaolou and thus Bouyei diaojiaolou are difficult to find. Located about 21 kilometres away from the city of Guiyang, Zhenshan village in Guizhou province has a mixed community of Bouyei and Miao people, with Bouyei making up about 75% of its population. Though most of the buildings in Zhenshan are made of stone, a few are made of both wood and stone in the diaojiaolou style. Alternatively, some of the Bouyei villages near the Nanpan River in Yunnan province contain several diaojiaolou.

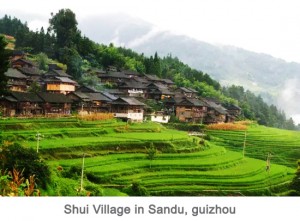

- Shui Diaojiaolou

The Shui dwellings are not typical diaojiaolou and so are often referred to as “woodpile dwellings”. This is because the stilts on the ground level are very short and the ground level will usually have walls, meaning the house looks kind of like a woodpile. Shui diaojiaolou will only ever have an odd number of rooms, since there is a taboo on even numbers in Shui culture. There are some small Shui villages in Guizhou province is the perfect place to admire these quaint little “woodpiles”.

The Shui dwellings are not typical diaojiaolou and so are often referred to as “woodpile dwellings”. This is because the stilts on the ground level are very short and the ground level will usually have walls, meaning the house looks kind of like a woodpile. Shui diaojiaolou will only ever have an odd number of rooms, since there is a taboo on even numbers in Shui culture. There are some small Shui villages in Guizhou province is the perfect place to admire these quaint little “woodpiles”.

Join a tour with us to explore more about Diaojiaolou: Explore the Culture of Ethnic Minorities in Guizhou

Xiabanliao

The sleepy village of Xiabanliao, located just southwest of Tianluokeng village and Shuyang Town, has been the home of the Liu clan for twenty-five generations. And, when you take in the lush greenery of the surrounding mountains and listen to the soft bubbling of nearby brooks, you’ll understand why they’ve stayed for so long! Yet Xiabanliao isn’t just your ordinary Chinese village; it houses one of the most magnificent architectural wonders the country has to offer.

The Tulou of Fujian are huge earthen fortresses that were designed to protect inhabitants from bandits. They have enjoyed great fame in recent years due to their unique appearance and unmatched fortitude. Xiabanliao’s Yuchang Lou, which was built by the Liu clan in 1308 during the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368), is one of the oldest and most resilient of them all. At the grand old age of 700, this tulou is still home to 23 families and about 120 people from the Liu clan. It may not have all the modern conveniences of a new home, but at least the Liu family never have to worry about a mortgage! It towers in at five-storeys in height and 36 metres in diameter, making it is the tallest tulou in China.

In spite of its age, the 25 kitchens on its ground floor are all equipped with their own private well, making it the only tulou in existence with such a convenient water supply. With 250 rooms, 25 kitchens, and a spacious courtyard in the centre, Yuchang Lou is so roomy that it could almost be called a village itself!

In spite of its age, the 25 kitchens on its ground floor are all equipped with their own private well, making it the only tulou in existence with such a convenient water supply. With 250 rooms, 25 kitchens, and a spacious courtyard in the centre, Yuchang Lou is so roomy that it could almost be called a village itself!

In recent years, it has earned the alternate name “the zigzag building” because the wooden post structure within the tulou, which is meant to be vertical, appears to zigzag left and right on the 3rd and 4th floors. This bizarre phenomenon was not intentional but was in fact due to an error made in measuring the building materials. Don’t let the unsteady appearance fool you; this tulou has survived more natural disasters, wars, and sieges than you can count!

Xiabanliao is one of the many wonderful stops on our travel: Explore the distinctive Tulou(Earthen Structure)

Taxia

The ancient Hakka village of Taxia, tucked away in the lush green mountains of Fujian, is one of the oldest and most spectacular villages China has to offer. It is located in a valley just west of Shuyang Town and is split by a river, which flows through the heart of the village and is lined by over 20 traditional Tulou. These gigantic, fortress-like buildings are made of packed earth and resemble fortified villages. They come in a number of styles, from those of a square or rectangular shape to round and oval ones. They were initially built to protect inhabitants from bandits and wild animals but have seemingly failed to shield them from the curiosity of tourists!

That being said, Taxia is a sleepy village that sees very little traffic and the locals, who have long become accustomed to rural life, while away the hours fishing, farming, and drinking tea. Sometimes it really is the simple things that make life worth living! The village was established in 1426 by the Zhang family but most of the remaining buildings were constructed during the 18th century, with the oldest, Fuxing Lou, having been built in 1631. Diaojiaolou or stilted wooden houses are also littered along the riverbanks of Taxia and only add to the idyllic pastoral scenery. The large tulou made of rich earth and the rustic wooden Diaojiaolou appear to be at one with both the manmade and natural surroundings.

The village’s main attraction is the Zhang Family’s Ancestral Hall, which is located near a pond and flanked by 20 stone flagpoles that rise up like a petrified forest. This shrine to the Zhang’s ancestors was built over 400 years ago and is one of the most well-preserved of its kind in the country. The gateway is engraved with a vivid image of two dragons playing with a pearl, inlaid beautifully with coloured ceramic chips, and the whole compound is embossed with lively decorations of Chinese deities, legendary figures, mythical creatures, wild animals, and charming flowers. At the back of the hall, a dense forest creeps its way up the mountains.

The village’s main attraction is the Zhang Family’s Ancestral Hall, which is located near a pond and flanked by 20 stone flagpoles that rise up like a petrified forest. This shrine to the Zhang’s ancestors was built over 400 years ago and is one of the most well-preserved of its kind in the country. The gateway is engraved with a vivid image of two dragons playing with a pearl, inlaid beautifully with coloured ceramic chips, and the whole compound is embossed with lively decorations of Chinese deities, legendary figures, mythical creatures, wild animals, and charming flowers. At the back of the hall, a dense forest creeps its way up the mountains.

Bizarrely, an almost exact replica of this ancestral hall can be found in Taiwan’s Tainan County and was built during the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912) by members of the Zhang family who had moved there. Evidently the Zhangs were a wealthy bunch, but not very creative!

On hot summer nights, the village comes to life as countless fireflies wind their way through the streets and create a sort of fairy tale atmosphere. Imagine spending a balmy evening watching these ethereal lights dance their way through the long grass or skitter above the surface of the river. I can’t think of anything more romantic!

Taxia is one of the many wonderful stops on our travel: Explore the distinctive Tulou(Earthen Structure)

Tianluokeng

Tianluokeng is perhaps one of the most famous villages in Fujian but, with a name that literally means “River Snail Pit”, you’re probably wondering why. Is it full of river snails? Do they “pit” the snails against each other? Of course not! Tianluokeng achieved its fame because it is one of the many stunning villages in rural Fujian that boast magnificent earthen buildings known as Tulou.

The village’s name may originate from a Fujian folktale known as “The Snail Girl”, in which a poor young farmer named Xie Duan is helped by and eventually falls in love with a snail fairy called a tianluo. Some local legends even suggest that the founder of Tianluokeng, Wong Baisanlang, was helped by a fairy named Miss Tianluo. This may explain why the local farmers move at a snail’s pace!

The village rests just outside of Shuyang Town and is home to a cluster of five tulou. These gigantic, fortress-like buildings are made of packed earth and resemble fortified villages. If you look closely at their upper levels, you can still see the small gun holes that were used to shoot at bandits. Snails may hide in their shells in times of danger, but the locals of Tianluokeng preferred a more aggressive approach!

The cluster is made up of one square-shaped tulou in the centre with three round tulou and one oval-shaped tulou surrounding it. Its unusual appearance has earned it the name “four dishes and one soup”, as it resembles the layout for an average family dinner in China. Just don’t try to eat out of these dishes, or you’ll end up the size of a building yourself!

The square tulou in the centre is known as “Buyun Lou” or “Reaching for the Clouds Building” and is the oldest of the set, having been built in 1796. Unfortunately its three-storey high exterior was not enough to discourage ne’er-do-wells, as it was burnt down by bandits in 1936 and had to be rebuilt in 1953. Its four sets of stairs were designed to express the founder’s wish that his descendants achieve greatness “step-by-step”. At least he provided them with plenty of fire exits!

The square tulou in the centre is known as “Buyun Lou” or “Reaching for the Clouds Building” and is the oldest of the set, having been built in 1796. Unfortunately its three-storey high exterior was not enough to discourage ne’er-do-wells, as it was burnt down by bandits in 1936 and had to be rebuilt in 1953. Its four sets of stairs were designed to express the founder’s wish that his descendants achieve greatness “step-by-step”. At least he provided them with plenty of fire exits!

Hechang Lou was built not long thereafter and, in 1930, the circular Zhenyang Lou followed. In 1936 Ruiyun Lou was constructed and the last of the bunch, Wenchang Lou, was completed in 1966. The sheer size of these tulou is a miracle in itself, as each one may have taken upwards of two years to build. This means the entire complex would have taken at least ten years to finish!

According to the Chinese philosophy of Feng Shui[1], the placement of the five tulou is particularly auspicious. It is believed that bad luck is more likely to hit the corners of buildings, so many of the tulou are circular in the hopes that misfortune will slide off of their round roofs. Since the square-shaped Buyun Lou is the only one that has corners and is coincidentally the only one to have been burnt down, there may be something to this theory! Nowadays the corners of Buyun Lou are bedecked with lucky symbols in the hopes of warding off evil. Let’s just hope they fireproofed it too!

[1] Feng Shui: This theory is based on the premise that the specific placement of certain places or objects will bring good luck.

Tianluokeng is one of the many wonderful stops on our travel: Explore the distinctive Tulou(Earthen Structure)

Yintan

Obscured by misty mountains and dense green forests, Yintan is a gem largely hidden from the rest of the world. This small Dong village just 20 kilometres (12 mi) north of Congjiang City is home to 1,700 people in 354 households and, isolated as it is, has harboured traditional Dong culture for generations. The gate is flanked by ancient Chinese yew trees, which give the village an air of mysticism as you enter. Even the name “Yintan” (银潭), meaning “Small Silver Lake”, has a certain ethereal quality to it.

Since it is so remote and has not yet been geared up for tourism, visitors rarely venture to Yintan and this only adds to its undeniably charm. While in the more popular Dong villages you’ll find yourself regularly rubbing elbows with other tourists, in Yintan the peaceful atmosphere means you can truly relax and enjoy traditional Dong culture.

The village is home to numerous Diaojiaolou, or wooden houses suspended on stilts, which climb up the mountain and mingle seamlessly with the natural scenery. These stilted dwellings are punctuated by three magnificent drum towers, which were all built during the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912) but are of different styles. Though their paint may have faded and their wood may be chipped, watching the sun set behind these towering edifices on a balmy summer’s evening is still just as breath-taking.

Yintan has also managed to maintain a few ancient opera stages, where performances of all kinds take place. From hearty dancing to piercing opera, the village locals really know how to enjoy the simple things in life! Unlike many other Dong communities, where youths only don their traditional outfits on festival occasions, almost all of the villagers in Yintan regularly wear their characteristic indigo-coloured clothes all year round. These clothes are handmade using the ancient tradition of cloth weaving and dyeing, which was passed on to them by their ancestors.

Yintan has also managed to maintain a few ancient opera stages, where performances of all kinds take place. From hearty dancing to piercing opera, the village locals really know how to enjoy the simple things in life! Unlike many other Dong communities, where youths only don their traditional outfits on festival occasions, almost all of the villagers in Yintan regularly wear their characteristic indigo-coloured clothes all year round. These clothes are handmade using the ancient tradition of cloth weaving and dyeing, which was passed on to them by their ancestors.

Almost every household in the village has a barrel for preparing indigo dye and almost every piece of clothing worn by the locals will have been made entirely by them. If you happen to be passing through Yintan on a hot summer’s day, you may even notice the freshly dyed clothes hanging from the balconies. Just don’t stand under them, or you’ll end up with indigo hair!

Join our travel to visit the tranquil Yintan Village: Explore the culture of Ethnic minorities in Southeast Guizhou

Shaxi

The sleepy town of Shaxi near the Heihui River is a far cry from what it once was. However, go there any given Friday and you’ll be met with the bustling local market, the last remnant of a trading culture that has all but disappeared in modern-day China. Like Dali Ancient Town and Shuhe Town, Shaxi once prospered thanks to the ancient Tea-Horse Road but, unlike its local counterparts, it has not yet suffered from the commercialisation that tourist towns inevitably succumb to. Though Shaxi boasts a few Western-style restaurants and boutique hotels, its relative inaccessibility compared to many of the other ancient towns in Yunnan means it does not receive the hordes of tourists that can make these spots a little less magical.

During the Tang Dynasty (618-907), Shaxi became one of the focal trade hubs along the Tea-Horse Road and by the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1912) dynasties it had flourished into one of the most affluent towns in Yunnan. Shaxi’s success largely arose from the salt wells that were dug near the town. It soon became the salt trade capital and, with salt being one of the most valuable commodities at the time, it prospered far beyond expectation. Revenge may be sweet, but success is evidently salty! This allowed the town to expand and many of the elaborate buildings found throughout Shaxi were erected during this time.

The town is largely inhabited by the Bai ethnic minority and many of its old buildings follow the Bai-style of “three rooms and one wall screening”. The house will usually consist of one main room, two side rooms and a “shining wall” that faces west so as to reflect light back into the house at sunset. The houses normally have three storeys in total and nine rooms, as nine is an auspicious number in Bai culture. The ground floor usually consists of one large sitting room flanked by two bedrooms, while the upper floors are used for storage with a special room set aside for the ancestral shrine.

Life in Shaxi mainly revolves around Square Street, the town’s central square. This ancient plaza is covered in red sand bricks and has two Chinese scholar trees standing at its centre that are each centuries old. It is still fully functioning on market day and is surrounded by a number of small temples, shops, teahouses and restaurants. It is flanked on its east side by an ancient stage and on its west by the 600-year-old Xingjiao Temple. The many ancient alleyways that branch out from Square Street are the backbone of Shaxi and provide access to its outer reaches. They lead to the village gates and pass by ancient caravansaries, eventually heading out towards Dali, Tibet and the salt wells.

The ancient stage is widely considered to be the heart and soul of Shaxi. The craftsmanship with which it was made is palpable in its many intricate carvings. It was built during the Qing Dynasty and is part of the three-storey Kuixing Pavilion. If you pay 10 yuan (about £1), you can ascend the ancient stage and head up to an exhibition of locally excavated cultural relics on the pavilion’s second storey. Just don’t linger too long on the stage, or the locals might expect a performance from you!

If you fancy getting in touch with the town’s history, you should certainly take a trip to Ouyang House. It was one of the original caravansaries and has been home to generations of muleteers over a period of one hundred years. In the early 1900s, the Ouyang family opened their house to passing caravans and offered food, lodgings and entertainment. They swiftly became the leading innkeepers in Shaxi and their substantial income enabled them to renovate and extend their inn. Nowadays, you can pay just 5 yuan (about 50p) to take a tour of the house and marvel at its ancient stables, guest quarters, kitchen, and ancestral shrine.

In spite of all these visual wonders, the must-see attraction in Shaxi is the town market, which has supposedly been held weekly since 1415. Although it started as a small affair, it has now become an all-consuming venture that billows out from the town square and floods the streets of Shaxi every week. From 10am till 5pm every Friday, goods ranging from washing machines to embroidered shoes and exotic fruits can be purchased at this eclectic market. It is a living remnant of Shaxi’s history as a trading post and is a spectacle of vibrancy, colour and animation that should not be missed.

Not far from the town you’ll find Mount Shibao, which is a mountain that has been delicately engraved with Buddhist carvings that date back to the 7th century. These 1,300-year-old carvings, punctuated by small temples along the mountainside, are truly stunning and make for a wonderful day out. If you decide to cycle out of the town, there are many small Bai and Yi villages in the Shaxi Valley that are only a short distance away and each boast their own unique attractions, from the renovated Pear Orchard Temple in Diantou Village to the Kuixing Pavilion of Changle Village.

If possible, we recommend you aim to catch the Temple Fair of Prince Shakyamuni, which takes place on the 8th day of the 2nd month according to the Chinese lunar calendar. During this festival, locals in colourful traditional clothes gather at Xingjiao Temple and parade through the streets carrying statues of Shakyamuni[1], while a team of people beat gongs and drums to liven up the procession. Performances will take place on the ancient stage throughout the festival and the celebrations carry on late into the night, electrifying the town square with bright lights, lively music and joyous dancing.

[1] Shakyamuni: One of the titles of Gautama Buddha, the central figure of the Buddhist faith. It is derived from the name Sakya, which is where he was born.