The Qianling Mausoleum is unique in that the main tomb has not been looted by grave robbers nor has it been excavated, meaning it has remained sealed and untouched for over 1,300 years. Thus, of the 18 Tang Dynasty Mausoleums, the Qianling Mausoleum is considered to be the most well-preserved. The main tomb houses one of China’s most controversial royal figures, Empress Wu Zetian, who was the only woman to have ever formally ruled China. She is also the only Empress to have been buried alongside her husband, the Emperor. The tomb itself follows the same structural pattern as Zhaoling Mausoleum in that it has been built into the side of a mountain. Only members of the imperial family were allowed to build their mausoleums into natural mountains and, of the 18 Tang Dynasty emperors, 14 of them chose to have mountains serve as their burial mounds. Though in scale Qianling Mausoleum may not be as impressive as the colossal Zhaoling Mausoleum, in terms of artistic beauty it is unmatched. Littered throughout the mausoleum you’ll find statues, murals and painted pottery, all a tableau of ancient China frozen in time. From the haunting stone funeral procession that leads to the Emperors tomb to the underground tombs of Princes and Princesses that have now been opened to the public, the Qianling Mausoleum takes you back to a time when men were gods and built monuments so as to be remembered for time immemorial.

Qianling Mausoleum is located on Mount Liang, about 80 kilometres (50 miles) northwest of Xi’an, and was built in 684 A.D., a year after Emperor Gaozong suffered the debilitating stroke that killed him. With the Leopard Valley to the east and the Sand Canyon to the west, the Mausoleum on Mount Liang is the perfect scenic spot to enjoy the diversity of landscapes in China. On the surface of the Mausoleum there were once 378 magnificent buildings, including the Sacrificial Hall, the Pavilion, and the Hall of Ministers. Sadly these surface buildings have all but disappeared, leaving only their underground counterparts. Aside from these surface buildings, which were relatively common among Tang Emperor’s tombs, Qianling Mausoleum has several features that make it unique among the other mausoleums. The burial mounds on the southern peak of Mount Liang each have towers erected at the centre of each mound and are thus named “Naitoushan” or “Nipple Hills” due to their resemblance to breasts. These Nipple Hills form a sort of gateway into the Mausoleum, creating a visual effect that is both stunning and exclusive to Qianling Mausoleum. The main imperial tomb, however, is located on the northern peak. There you’ll find the tallest burial mound and a 61 metre (200 ft.) long, 4 metre (13 ft.) wide tunnel carved out of the mountain that leads into the inner tomb chambers. This is the final resting place of Emperor Gaozong and Empress Wu Zetian, which has remained unopened to this day.

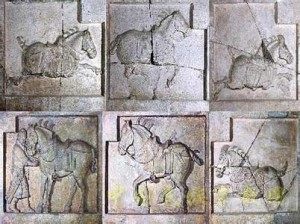

The most magnificent and otherworldly feature of Qianlong Mausoleum are the stone statues that have braved the elements and remained suspended in time for over a thousand years. If you follow the Spirit Way that leads to the Emperor’s tomb, you will undoubtedly discover the 124 stone statues that serve as his funeral procession. These include statues of horses, winged horses, horses with grooms, lions, officials, foreign envoys and, most bizarre of all, ostriches. The first ostrich was presented to the Tang court by a khan of the Western Turks in 620 A.D. and the Tushara Kingdom sent another one in 650 A.D. It is believed that early Chinese representations of phoenixes were based on these ostriches. The ostriches at Qianling Mausoleum serve as a symbol of the Tang Dynasty’s power and influence over its foreign neighbours.

The most magnificent and otherworldly feature of Qianlong Mausoleum are the stone statues that have braved the elements and remained suspended in time for over a thousand years. If you follow the Spirit Way that leads to the Emperor’s tomb, you will undoubtedly discover the 124 stone statues that serve as his funeral procession. These include statues of horses, winged horses, horses with grooms, lions, officials, foreign envoys and, most bizarre of all, ostriches. The first ostrich was presented to the Tang court by a khan of the Western Turks in 620 A.D. and the Tushara Kingdom sent another one in 650 A.D. It is believed that early Chinese representations of phoenixes were based on these ostriches. The ostriches at Qianling Mausoleum serve as a symbol of the Tang Dynasty’s power and influence over its foreign neighbours.

Similarly, the sixty-one stone envoys that perpetually mourn Emperor Gaozong’s death were directly commissioned by Empress Wu Zetian and designed after the sixty-one foreign envoys that were physically present at Emperor Gaozong’s funeral. Each figure is wearing a long robe with a wide belt and boots and, if you look closely, you’ll find the name of each individual and the country he represented carved on his back. These foreign envoys were constructed to further symbolise the Tang Dynasty’s far reaching influence and powerful empire. Tragically, for reasons unknown, these sixty-one statues have been decapitated.

Surrounding the main tomb, archaeologists have also recovered four gates, parts of the inner wall, and parts of the outer wall that guarded the tomb, along with remnants of houses that once belonged to workers charged with maintaining the tomb. The four gates are called Zhu Que Men (Rosefinch Gate) to the south, Xuan Wu Men (Mystical Power Gate) to the north, Qing Long Men (Black Dragon Gate) to the east, and Bai Hu Men (White Tiger Gate) to the west. Near the main tomb you’ll also find the magnificent Qijie Bei or “Tablet of the Seven Elements”, which is so called because it symbolises the Sun, Moon, Metal, Wood, Water, Earth and Fire, the seven elements in ancient Chinese philosophy. This tablet carries an inscription describing the achievements of the Emperor, which was composed by the Empress Wu Zetian and written in the calligraphic style of Emperor Zhongzong (Emperor Gaozong’s son). Interestingly, near the Tablet of the Seven Elements, there sits the Blank Tablet, which has dragons and oysters carved upon it but no inscription. It is the only blank tablet to be found in any royal mausoleum in China and was erected by Empress Wu Zetian, who stated in her will: “My achievements and errors must be evaluated by later generations, therefore carve no characters on my stele[1]”. This may seem like an odd thing for anyone to say, particularly from the only woman to have ever ruled as Emperor, and it shines a light directly on the controversy surrounding Wu Zetian.

Although the Emperor’s tomb has not been excavated, the tombs of Crown Prince Zhanghuai, Prince Yide and Princess Yongtai have all been unearthed and opened to the public. The one thing these three royal figures had in common was that they were all put to death by their mother and grandmother respectively, Wu Zetian, when they were still young. These three unfortunate youths, who suffered tragic deaths, were not even honored with imperial tombs until Empress Wu Zetian finally died in 706 A.D and their brother and father respectively, Emperor Zhongzong, was finally allowed to give his brother and children a proper burial. Wu Zetian was not only implicated in the deaths of these three relatives but also in the deaths of two of her other children and several other family members, friends and officials that either displeased her or threatened her claim to the throne. Thus you can understand why, in light of all these nefarious deeds, Wu Zetian’s tombstone has remained blank for over a thousand years. Though Wu Zetian’s reign of tyranny has long ended, her exploits have not been forgotten.

Although the Emperor’s tomb has not been excavated, the tombs of Crown Prince Zhanghuai, Prince Yide and Princess Yongtai have all been unearthed and opened to the public. The one thing these three royal figures had in common was that they were all put to death by their mother and grandmother respectively, Wu Zetian, when they were still young. These three unfortunate youths, who suffered tragic deaths, were not even honored with imperial tombs until Empress Wu Zetian finally died in 706 A.D and their brother and father respectively, Emperor Zhongzong, was finally allowed to give his brother and children a proper burial. Wu Zetian was not only implicated in the deaths of these three relatives but also in the deaths of two of her other children and several other family members, friends and officials that either displeased her or threatened her claim to the throne. Thus you can understand why, in light of all these nefarious deeds, Wu Zetian’s tombstone has remained blank for over a thousand years. Though Wu Zetian’s reign of tyranny has long ended, her exploits have not been forgotten.

If you visit the tombs today, you’ll find a much more positive representation of ancient China. The three tombs that have been opened up to the public are covered in stunning murals of typical scenes in the Imperial Court, including beautiful maidservants, nobles playing Polo on horseback and royals receiving their foreign guests. Though these paintings have been worn by time, the exuberant colours and vivid facial expressions of the characters within them still evoke a real sense of how extravagant life must have been during the Tang Dynasty. Princess Yongtai’s tomb has been converted into a museum, where you’ll find a collection of the 4,300 historical relics that were exhumed from the three tombs. From the delicately carved jade funeral eulogiums to the painted figures of riders with their horses gilt faced, inlaid lavishly with gold, we’re sure you’ll find a trip to Qianlong Museum and Qianlong Mausoleum both rewarding and fascinating. From the outset, it is truly a feast for the eyes.

[1] Stele: An upright stone slab or pillar that bears an inscription and usually marks a burial site, like a tombstone.

After the death of the Emperor in 210 B.C., the Mausoleum was hermetically-sealed and remained unopened for nearly 2,000 years. It wasn’t until 1974, when some farmers were attempting to dig a water-well near Mount Li, that Pit one of the Terracotta Army was accidentally unearthed. Archaeologists flocked to the site and began excavating the area, eventually discovering three more pits of Terracotta Warriors in the process. The warriors were all found arranged as if to protect the tomb from the east, which is where all of the states that were conquered by the Qin Dynasty lay. To date, approximately 8,000 soldiers, 130 chariots with 520 horses and 150 cavalry horses have been uncovered from these pits.

After the death of the Emperor in 210 B.C., the Mausoleum was hermetically-sealed and remained unopened for nearly 2,000 years. It wasn’t until 1974, when some farmers were attempting to dig a water-well near Mount Li, that Pit one of the Terracotta Army was accidentally unearthed. Archaeologists flocked to the site and began excavating the area, eventually discovering three more pits of Terracotta Warriors in the process. The warriors were all found arranged as if to protect the tomb from the east, which is where all of the states that were conquered by the Qin Dynasty lay. To date, approximately 8,000 soldiers, 130 chariots with 520 horses and 150 cavalry horses have been uncovered from these pits. The Museum of Qin Terracotta Warriors and Horses and the Qin Shi Huang Mausoleum have now been incorporated into one tourist attraction known as Emperor Qin Shi Huang’s Mausoleum Site Park. There you’ll find regular free shuttle buses that will take you from the site of the Terracotta Army to Lishan Garden. Lishan Garden acts as the perfect complement to the Terracotta Army as it contains Qin Shi Huang’s burial mound, ritual sacrifice pits, the Museum of Terracotta Acrobatics, the Museum of Terracotta Civil Officials, the Museum of Stone Armour and the Museum of Bronze Chariots and Horses. The Museum of Bronze Chariots and Horses is a wonderful exhibition of all the figures found throughout the pits that are crafted from bronze rather than terracotta. They loom out of their glass cases, lifelike in their shimmering skin. The other museums are based around pits where terracotta figures are still being excavated and present the perfect opportunity to watch a live archaeological dig. The chance to watch the Terracotta figures being unearthed and thus the opportunity to watch history being made is one that we know you won’t want to pass up. The only area that is not open to the public and has not been excavated is the main tomb, where the Emperor’s remains rest. In spite of an on-going debate as to whether the tomb should be opened or not, it is universally thought that it will remain undisturbed as a mark of respect to the Emperor.

The Museum of Qin Terracotta Warriors and Horses and the Qin Shi Huang Mausoleum have now been incorporated into one tourist attraction known as Emperor Qin Shi Huang’s Mausoleum Site Park. There you’ll find regular free shuttle buses that will take you from the site of the Terracotta Army to Lishan Garden. Lishan Garden acts as the perfect complement to the Terracotta Army as it contains Qin Shi Huang’s burial mound, ritual sacrifice pits, the Museum of Terracotta Acrobatics, the Museum of Terracotta Civil Officials, the Museum of Stone Armour and the Museum of Bronze Chariots and Horses. The Museum of Bronze Chariots and Horses is a wonderful exhibition of all the figures found throughout the pits that are crafted from bronze rather than terracotta. They loom out of their glass cases, lifelike in their shimmering skin. The other museums are based around pits where terracotta figures are still being excavated and present the perfect opportunity to watch a live archaeological dig. The chance to watch the Terracotta figures being unearthed and thus the opportunity to watch history being made is one that we know you won’t want to pass up. The only area that is not open to the public and has not been excavated is the main tomb, where the Emperor’s remains rest. In spite of an on-going debate as to whether the tomb should be opened or not, it is universally thought that it will remain undisturbed as a mark of respect to the Emperor.