Resting on the southern bank of the Yellow River, the provincial capital of Zhengzhou represents the historical, cultural, and commercial heart of Henan province. While it may not be one of the most well-known cities in China, it is ranked as one of the Eight Great Ancient Capitals thanks to archaeological discoveries that were made in the region during the 1950s. Evidence found in the surrounding area proves that not only was it settled during the Neolithic Period (c. 8500-2100 BC), but that Zhengzhou was once a walled city dating all the way back to the Shang Dynasty (c. 1600-1046 BC).

Researchers believe it may have been the ancient Shang capital of Ao and it represents a treasure trove of Shang Bronze Age cultural relics. Over 3,500 years ago, this city would have been the site where artisans developed the first primitive forms of porcelain and bronze smelting. A green ceramic glazed pot that was unearthed in Zhengzhou is believed to be the oldest example of porcelain in the country. In short, you could almost say it put the china in China! The city was largely abandoned during the 13th century BC but remained occupied during the Zhou Dynasty (c. 1045-256 BC), as is demonstrated by the presence of Zhou tombs in the region.

It is widely believed that the area then became the fief of a family surnamed Guan and, during the 6th century BC, was named Guancheng or “City of Guan” for this reason. It wasn’t until 605 AD, during the Sui Dynasty (581-618), that it was finally named Zhengzhou. It rose to prominence during the Sui, Tang (618-907), and early Song (960-1279) dynasties, when it became the terminus along the New Bian section of the Grand Canal[1]. This was the main conduit via which grain was transported from southern China to the westward capitals of Luoyang and Chang’an (modern-day Xi’an), as well as to the armies along the northern frontiers. However, during the late Song Dynasty, Zhengzhou was plunged into irrelevance when the capital was moved eastward to Kaifeng.

Nowadays, the city is a bustling metropolis, bearing little resemblance to the primeval capital it once was. However, its most popular tourist draw remains the Shang Dynasty Ruins in the downtown area, where visitors continue to marvel at the mud-brick city walls that have stood for over 3,000 years. Many of the valuable items that were unearthed at the site, such as rare bronzes, jade articles, and porcelain wares, have been relocated to the Henan Museum in the northern part of the city. One of the museum’s greatest treasures is a rare ivory sculpture of a cabbage, complete with its own vividly carved insects. At this museum you’ll be sure to talk of many things, of cabbages and kings!

Another of Zhengzhou’s most important historical sites, the Erqi Memorial Tower, is located in the city centre. This 14-storey double tower commemorates the railway workers involved in the Erqi Strike, which took place on February 7th 1923. While it towers in at an impressive 63 metres (207 ft.) in height, it is no match for the city’s mammoth 388-metre (1,273 ft.) tall Zhongyuan Tower. Although it is primarily used as a television tower, it comes complete with its own observation deck and 200-guest revolving restaurant. The third and fourth floors of the observation deck are blanketed in the world’s largest panoramic painting, which is 18 metres (59 ft.) in height and 164 metres (538 ft.) in length. To put that into perspective, that’s approximately 6 times the height of an African elephant and 33 times the length of an anaconda!

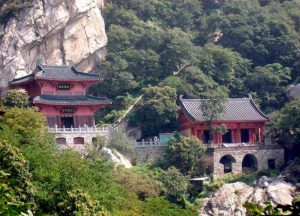

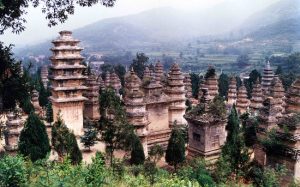

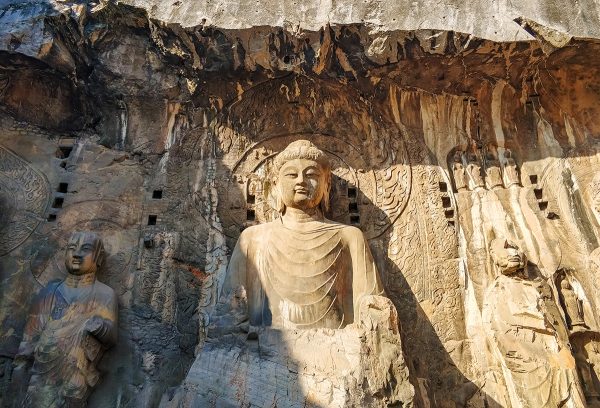

Once you’ve finished exploring the city, there are a number of spectacular UNESCO World Heritage Sites nearby that are sure to tempt you. About 80 kilometres (50 mi) southwest of downtown Zhengzhou, Mount Song rises up in the centre of the province. It is heralded as one of China’s Five Great Mountains, and is the home of the venerated Shaolin Temple. Famed as the birthplace of Chinese Kung-Fu, the Shaolin Temple and its accompanying Pagoda Forest are a must-see for any martial arts enthusiast. Just be sure not to get on anyone’s bad side; you never know who might be a Kung-Fu master!

Note:

[1] The Grand Canal: It is the longest canal in the world and starts in Beijing, passing through the provinces of Hebei, Shandong, Jiangsu, and Zhejiang before eventually terminating in the city of Hangzhou. It links the Yellow River to the Yangtze River and the oldest parts of it date back to the 5th century BC, although most of its construction took place during the Sui Dynasty (581-618).

Nowadays it is generally separated into four sub-styles: Xiangfu, which originated from Kaifeng; Yudong, which arose in the Shangqiu region of eastern Henan; Yuxi, which became popular in the area surrounding the city of Luoyang; and Shahe, which came from Shahe County. Of these, the Yudong and Yuxi sub-styles are the most prevalent, and are known for their comedies and tragedies respectively.

Nowadays it is generally separated into four sub-styles: Xiangfu, which originated from Kaifeng; Yudong, which arose in the Shangqiu region of eastern Henan; Yuxi, which became popular in the area surrounding the city of Luoyang; and Shahe, which came from Shahe County. Of these, the Yudong and Yuxi sub-styles are the most prevalent, and are known for their comedies and tragedies respectively.