While there are innumerable temples dedicated to Confucius and Confucianism throughout China, the Temple of Confucius in the city of Qufu is the largest and most well-known. After all, Confucius was born in Qufu, and the temple was the first place where people would come to worship this noble sage. Its undeniable historical importance meant it was listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1994, alongside the Cemetery of Confucius and the Kong Family Mansion. After countless renovations and reconstructions, this colossal complex sprawls out over the verdant countryside of Shandong province, representing the second largest ancient building in China after the Forbidden City. It served as the prototype for many of the Confucian temples you’ll find across East Asia.

When Confucius passed away in 479 BC, China had yet to be unified as an empire under the First Emperor, Qin Shi Huang. The country was fractured into a myriad of vassal states, with Confucius living in a place known as the State of Lu. His death struck a major blow to the people of Lu and, just two years after his passing, the Duke of Lu consecrated his former home as a temple. As time went on, his teachings spread across the world and he began to be recognised as one of the most influential philosophers in human history.

During the Han Dynasty (206 BC–220 AD), Emperor Gao travelled to Qufu in order to make sacrifices at the Temple of Confucius. This set an example for many emperors and high officials to follow, establishing Confucius as a figure worthy of veneration even from an emperor. In total, 12 different emperors paid personal visits to the temple and about 100 others sent high-ranking deputies in their place. You know you’re a pretty important person when the Emperor himself is taking time out of his busy schedule to personally visit your childhood home!

In 611, Confucius’ original three-room house was removed from the temple complex and placed just east of the temple, where it would be developed into an aristocratic mansion for his direct male descendants under the title the Kong Family Mansion. By the Song Dynasty (960-1279), the temple had been extended into a colossal complex with three sections, four courtyards, and over 400 rooms. However, as the old saying goes, nothing is built to last! In 1214, fire and vandalism brought on by the invasion of the Jurchen-led Jin Dynasty[1] (1115-1234) virtually destroyed the temple. It wasn’t until 1302, during the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368), that it was finally restored to its former glory.

Yet it seems arson must have been a popular hobby in Qufu, because the temple would be damaged by fire a further two times, once in 1499 and once in 1724. Through its long history, this rather unlucky temple has undergone 15 major renovations and 31 large scale repairs! The most significant renovation took place during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), after the 1499 fire, when the complex underwent a major redesign and has remained virtually the same in appearance to this day.

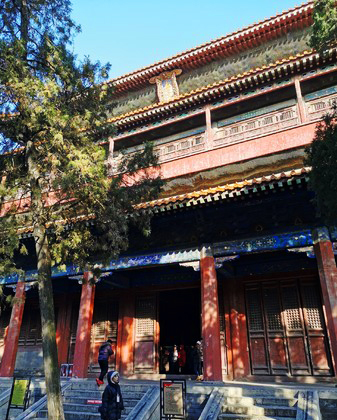

Since this renovation took place not long after the construction of the Forbidden City, much of the architecture in the Temple of Confucius greatly resembles its imperial counterpart. Red walls, yellow roofs, and marble stonework endow it with the stately elegance of a palace. The main buildings run along a north to south axis, while the attached buildings are arranged symmetrically. Altogether there are three halls, one pavilion, one altar, three ancestral temples, 466 rooms, 54 gateways, over 1,000 steles, and more than 1,250 ancient trees.

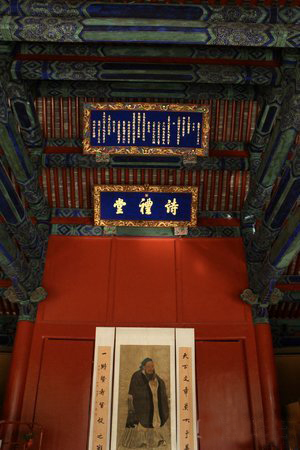

Visitors first walk through the main gateway, known as the Lingxing Gate. Lingxing was the name given to the legendary star of literacy, which emperors would offer sacrifices to before making offerings to heaven. Resting at the centre of the complex is the temple’s main attraction: Dacheng or “Great Achievement” Hall. Having been originally built during the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912), it is widely considered to be the pinnacle of Qing art and architecture. This was the principal hall where emperors and high officials would offer sacrifices to Confucius.

It is supported by 28 lavishly decorated pillars, with 10 stone columns at the front intricately carved with coiled dragons. According to local rumour, these dragon columns had to be covered up during visits by the emperor because it was believed they would arouse his envy! In front of Dacheng Hall, the Apricot Pavilion commemorates how Confucius would teach his students under the tranquil shade of an apricot tree. On September 28th of every year, a ceremony is held in this pavilion to celebrate Confucius’ birthday. After all, when you’re arguably the greatest philosopher and thinker in Chinese history, the least you deserve is a little birthday cake!

Note:

[1] Jurchen Jin Dynasty (1115-1234): Led by the Jurchen clan, who were of Manchu descent and controlled most of northern China but were ultimately defeated by the rising Mongol Empire. Not to be confused with the imperial Jin Dynasty (265-420).