Forming part of the eastern border along the Gobi Desert, the Yin Mountains stretch for over 1,000 kilometres (631 mi) from Inner Mongolia to northern Hebei province. At points they rise to a mighty 2,180 metres (7,152 ft.) in height, while at others they drop to a modest 1,500 metres (4,921 ft.). Their northern slope is comparatively gentle, but the southern slope is steep and forms a sharp natural barrier against the plain below it. Yet it’s not the mountain range’s height that makes it so special. The range is home to over ten thousand cliff paintings known as petroglyphs, where the rock’s surface has been incised, carved, or abraded to form a primitive work of art. Since prehistoric times, these mountains and their surroundings have served as the muse for countless individuals.

These petroglyphs can be separated into four main sets: the first and oldest set, which dates back to the Xia (c. 2100-1600 BC), Shang (c. 1600-1046 BC), and Zhou (c. 1045-256 BC) dynasties; the second set, which were carved by Xiongnu nomads and range from the Spring and Autumn Period (c. 771-476 BC) to the Han Dynasty (206 BC–220 AD); the third set, which portrays distinctly Turkish characteristics and dates back to between the Jin Dynasty (265-420 AD) and the Tang Dynasty (618-907); and the final set, which were executed by Mongolian tribes sometime from the Song Dynasty (960-1279) to the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912).

Some of the oldest rock paintings were examined as early as the 5th century by the geologist Li Daoyuan of the Northern Wei Dynasty (386–535). While his findings represent the earliest record of the paintings, they weren’t formally surveyed until 1976. From then on, experts, scholars, and tourists have been drawn to the mountain range, tempted by the opportunity to catch a glimpse of our prehistoric origins. The paintings provide an invaluable insight into the lifestyle, beliefs, and customs of the ancient nomads that once roamed these open plains.

Some of the oldest rock paintings were examined as early as the 5th century by the geologist Li Daoyuan of the Northern Wei Dynasty (386–535). While his findings represent the earliest record of the paintings, they weren’t formally surveyed until 1976. From then on, experts, scholars, and tourists have been drawn to the mountain range, tempted by the opportunity to catch a glimpse of our prehistoric origins. The paintings provide an invaluable insight into the lifestyle, beliefs, and customs of the ancient nomads that once roamed these open plains.

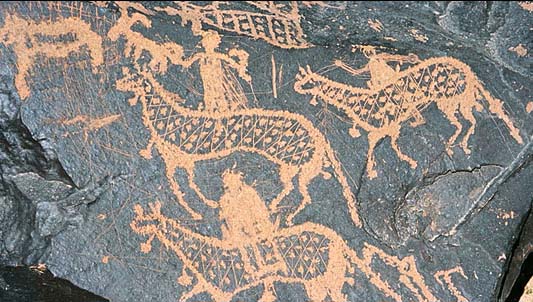

The paintings themselves are scattered throughout the mountain range, with the largest concentration being located on Mount Hei. The early paintings are dominated by scenes of hunting and feature a wide range of animals, including goats, sheep, antelopes, elks, moose, deer, horses, camels, wild ox, wild boar, rabbits, foxes, wolves, tigers, leopards, and even ostriches! Many of these species have since disappeared from the region, but these paintings act as a testament to their presence.

On many of the cliff-faces, a certain pattern emerges regarding the distribution of the paintings. While scenes of hunting and wild animals are found mostly towards the base or mid-point of the cliff, those of deities, celestial bodies, or constellations tend to be engraved high on steep cliffs or on giant rocks near valleys. This demonstrates an early veneration for religious figures and implies that, as with many primitive peoples, the nomads of the Yin Mountains associated the life-giving properties of water with the gods.

These early paintings were predominantly chiselled or ground into the rock using basic metal or stone tools, meaning they are often uneven in depth and density. The rock paintings of later periods are characterised by thinner and more superficial lines, which were formed by literally scratching into the rock-face using much slimmer utensils. As time went on and the paintings became more sophisticated, so too did their themes. Scenes of hunting are replaced by tableaus of herding and grazing domestic animals; the faces of anthropomorphic animal gods are gradually superseded by the distinctly human features of Buddhist deities; and simple skirmishes between different tribes become spectacles of brutal warfare. As society continues to advance at a rapid pace, these paintings serve as a poignant reminder of mankind’s humble beginnings.

These early paintings were predominantly chiselled or ground into the rock using basic metal or stone tools, meaning they are often uneven in depth and density. The rock paintings of later periods are characterised by thinner and more superficial lines, which were formed by literally scratching into the rock-face using much slimmer utensils. As time went on and the paintings became more sophisticated, so too did their themes. Scenes of hunting are replaced by tableaus of herding and grazing domestic animals; the faces of anthropomorphic animal gods are gradually superseded by the distinctly human features of Buddhist deities; and simple skirmishes between different tribes become spectacles of brutal warfare. As society continues to advance at a rapid pace, these paintings serve as a poignant reminder of mankind’s humble beginnings.