From singing sand dunes to unexplained lakes, the Badain Jaran Desert is marked by its mysterious natural wonders. It stretches across Inner Mongolia, Ningxia, and Gansu province and covers a colossal area of 49,000 square kilometres (19,000 sq. mi). Although it is considered part of the Gobi Desert, as an independent entity it technically ranks as the third largest desert in China. To the east, it is separated from the Ulan Buh Desert by Mount Lang, and only Mount Yabulai stands between it and the Tengger Desert to the southeast. To the southwest lies the famed Hexi Corridor, a major section of the ancient Silk Road; and to the west flows the Ejin River, which cuts it off from the hostile Taklamakan Desert.

While deserts are not typically known for their habitability, archaeological findings suggest that the Badain Jaran Desert was inhabited or at least ventured into by people from as early as the Paleolithic Era (roughly 2.6 million to 10,000 years ago)! During the Xia Dynasty (c. 2100-1600 BC), the area was settled by the Tangut people, who were known to have traded with merchants from the ancient region of Bactria (2200-1700 BC) in Central Asia. Nowadays the desert is a popular tourist attraction, with visitors flocking to marvel at its myriad of natural oddities.

The Badain Jaran Desert boasts some of the tallest stationary dunes on earth, with most of them averaging at around 200 metres (660 ft.) and some of them reaching over 400 metres (1,300 ft.) in height. Most of the dunes are not stationary, but the ones that are still have a shallow layer of sand at the top that is constantly shifting. It is the middle and lower layers of these dunes that remain static, as the sand in these layers has been compacted over a period of more than 20,000 years. This has caused the sand particles to harden, eventually transforming them into solid sand or sandstone.

The desert’s largest stationary sand dune, known as Bilutu Peak, towers in at a height of 500 metres (1,600 ft.) from base to peak, making it the tallest sand dune in Asia and the tallest stationary sand dune in the world. To put that into perspective, Bilutu Peak is over 50 metres (164 ft.) taller than the Empire State Building! While the size of the sand dunes is undoubtedly impressive, it is their capacity to sing that attracts tourists from across the globe. Often referred to as the singing sand dunes, whistling sands, or booming dunes, this fantastical phenomenon is shared by only 35 other beaches and deserts around the world.

For reasons that are not entirely known, the dunes emit a low pitched rumbling sound that can reach over 105 decibels and last for more than a minute. It is believed that the noise is caused by the electrostatic charge generated when wind pulls the top layer of shifting sand down the dune slope. However, it will only occur under very specific circumstances. The dunes are eerily silent during the winter, when the sand retains moisture from the rain. Even in the summer, this booming sound can only be generated on the leeward face of a dune with a slope that rises at an angle of at least 60 degrees or more. Although the booming dunes might be seasonal, it is possible to make the dunes burp all year round! By moving your hand gently through the dry sand of a booming sand dune, you can destabilise the upper layer of sand and cause it to emit a brief “burping” sound.

Between these sand dunes lies another of the desert’s strange secrets: over 140 colourful lakes scattered throughout its sandy expanse. These lakes are typically found in the valleys formed between the larger sand dunes and provide sustenance to the numerous camels, goats, and horses that are herded through the desert by nomads. Around many of the lakes, a green ring of vegetation sits in stark contrast to the barren desert that surrounds it. Some are freshwater lakes, while others are extremely salty. Large populations of brine shrimp, algae, and certain minerals cause some of the lakes to change colour at different times of the year.

It is believed that the lakes are formed from melted snow and spring water that trickles down from the nearby mountains and runs under the desert in underground streams, although the true source of the lake water has yet to be found. On the southeastern margin of the desert, the lakes are long and shallow, reaching depths of less than 2 metres (6 ft.). These lakes have a much lower salt concentration than the deeper oval-shaped lakes found further in, which can reach maximum depths of up to 15 metres (49 ft.).

It is believed that the lakes are formed from melted snow and spring water that trickles down from the nearby mountains and runs under the desert in underground streams, although the true source of the lake water has yet to be found. On the southeastern margin of the desert, the lakes are long and shallow, reaching depths of less than 2 metres (6 ft.). These lakes have a much lower salt concentration than the deeper oval-shaped lakes found further in, which can reach maximum depths of up to 15 metres (49 ft.).

These verdant oases in the otherwise desolate desert have allowed more than just plant life to flourish. Situated on the banks of a lake in the middle of the desert, the Badain Jaran Temple has been a centre for Tibetan Buddhism since it was built in 1868. Its isolated location means it has been untouched by the warfare and unrest that typically plagued other temples in China. Elaborate statues, wood carvings, relics, and a small white pagoda have all been beautifully preserved within this ancient temple complex.

On the northwestern edge of the desert lies the Ejin Banner, which once served as the hunting grounds of the fearsome Xiongnu people until the region was conquered by the Han Dynasty (206 BC–220 AD) in 121 BC. Nowadays its population is predominantly Han Chinese, but it is still regarded as a culturally Mongolian region. Within its vast expanse lie the ruins of Khara-Khoto, an ancient metropolis that was built by the Tangut people of the Western Xia Dynasty (1038–1227) and rose to become a major trading hub during the 11th century.

On the northwestern edge of the desert lies the Ejin Banner, which once served as the hunting grounds of the fearsome Xiongnu people until the region was conquered by the Han Dynasty (206 BC–220 AD) in 121 BC. Nowadays its population is predominantly Han Chinese, but it is still regarded as a culturally Mongolian region. Within its vast expanse lie the ruins of Khara-Khoto, an ancient metropolis that was built by the Tangut people of the Western Xia Dynasty (1038–1227) and rose to become a major trading hub during the 11th century.

The unusual terrain in the Badain Jaran Desert means that these attractions can only be reached by hiring a special jeep. Unlike other vehicles, these jeeps are designed to drive on sand, and are capable of ascending and descending the sand dunes. The climate in the Badain Jaran Desert oscillates between the temperate arid and the extremely arid, so it is of paramount importance to be prepared on your travels. Temperatures can rise to a sweltering 41 °C (106 °F) during the day and plummet to −30 °C (−22 °F) at night. When the sun is at its hottest, sand temperatures can easily exceed 80 °C (176 °F), so be sure to don appropriate footwear. In short, choose boots that were made for walking, not melting!

Nowadays, most Mongols live in modern apartment blocks or fixed residences. However, you’ll still find plenty of Mongol people maintaining their nomadic heritage and living on the grasslands in a type of portable domed tent known as a ger or yurt. Some people even alternate between the two; living in urban housing for part of the year and then shifting to a ger in order to tend to their livestock. The use of these unusual abodes dates back to the time of the mighty Genghis Khan, roughly around about the 12th century. With their bright white exteriors and perfectly rounded shape, these magnificent gers look like glittering pearls scattered across the jade-hued grasslands.

Nowadays, most Mongols live in modern apartment blocks or fixed residences. However, you’ll still find plenty of Mongol people maintaining their nomadic heritage and living on the grasslands in a type of portable domed tent known as a ger or yurt. Some people even alternate between the two; living in urban housing for part of the year and then shifting to a ger in order to tend to their livestock. The use of these unusual abodes dates back to the time of the mighty Genghis Khan, roughly around about the 12th century. With their bright white exteriors and perfectly rounded shape, these magnificent gers look like glittering pearls scattered across the jade-hued grasslands.

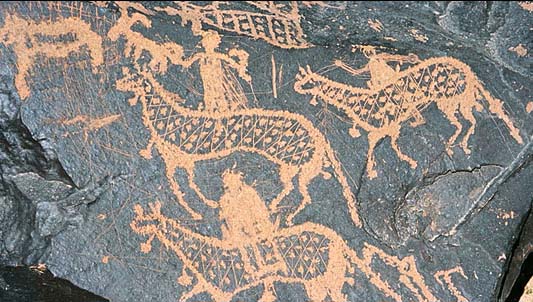

Some of the oldest rock paintings were examined as early as the 5th century by the geologist Li Daoyuan of the Northern Wei Dynasty (386–535). While his findings represent the earliest record of the paintings, they weren’t formally surveyed until 1976. From then on, experts, scholars, and tourists have been drawn to the mountain range, tempted by the opportunity to catch a glimpse of our prehistoric origins. The paintings provide an invaluable insight into the lifestyle, beliefs, and customs of the ancient nomads that once roamed these open plains.

Some of the oldest rock paintings were examined as early as the 5th century by the geologist Li Daoyuan of the Northern Wei Dynasty (386–535). While his findings represent the earliest record of the paintings, they weren’t formally surveyed until 1976. From then on, experts, scholars, and tourists have been drawn to the mountain range, tempted by the opportunity to catch a glimpse of our prehistoric origins. The paintings provide an invaluable insight into the lifestyle, beliefs, and customs of the ancient nomads that once roamed these open plains. These early paintings were predominantly chiselled or ground into the rock using basic metal or stone tools, meaning they are often uneven in depth and density. The rock paintings of later periods are characterised by thinner and more superficial lines, which were formed by literally scratching into the rock-face using much slimmer utensils. As time went on and the paintings became more sophisticated, so too did their themes. Scenes of hunting are replaced by tableaus of herding and grazing domestic animals; the faces of anthropomorphic animal gods are gradually superseded by the distinctly human features of Buddhist deities; and simple skirmishes between different tribes become spectacles of brutal warfare. As society continues to advance at a rapid pace, these paintings serve as a poignant reminder of mankind’s humble beginnings.

These early paintings were predominantly chiselled or ground into the rock using basic metal or stone tools, meaning they are often uneven in depth and density. The rock paintings of later periods are characterised by thinner and more superficial lines, which were formed by literally scratching into the rock-face using much slimmer utensils. As time went on and the paintings became more sophisticated, so too did their themes. Scenes of hunting are replaced by tableaus of herding and grazing domestic animals; the faces of anthropomorphic animal gods are gradually superseded by the distinctly human features of Buddhist deities; and simple skirmishes between different tribes become spectacles of brutal warfare. As society continues to advance at a rapid pace, these paintings serve as a poignant reminder of mankind’s humble beginnings.