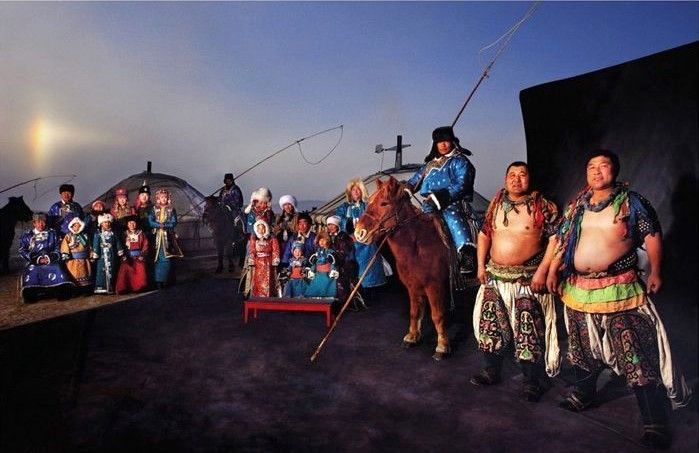

Unsurprisingly, the cuisine in Inner Mongolia has been heavily influenced by the Mongol ethnic minority, who make up a substantial proportion of the region’s population. Since Inner Mongolia shares its borders with Outer Mongolia and Russia, its cuisine has also incorporated features from traditional Mongolian, Chinese, and Russian cuisine. You could almost say it’s a real melting pot of cultures! Since the Mongolian people who inhabited the grasslands were conventionally nomadic and pastoral, they had to find a diet that would help them survive during the bitterly cold winters. Thus their cuisine places great emphasis on three categories of ingredients: “red food” (fatty meats), “white food” (dairy products), and wheat-based foods.

The extreme climate meant that spices and vegetables were not readily available, so they rarely feature in signature Mongolian dishes. Traditionally only a few native plants, such as wild spring onions and wild thyme, and hardy plants that grew on the steppes, such as buckwheat and millet, would be used in dishes, although nowadays the influx of Han Chinese immigrants means that other ingredients have been introduced to the Inner Mongolian palate.

Mongolian nomads typically farmed what they referred to as the “Five Snouts”: sheep, goats, yak, camels, and horses. Nowadays they also farm cattle, but cattle and goats are prized for their milk while horses, camels, and yak are considered valuable pack animals. This left the poor sheep with the task of providing most of the meat, which explains the marked preference for mutton in many Mongolian dishes.

Mutton from sheep raised on the grasslands is rumoured to be the best in China, as the sheep enjoy a diet of fresh grass and mineral water instead of man-made feed. Historically this hearty meat helped the local people to keep weight on during the winter, along with other “heavy” foodstuffs such as milk, cream, milk tea, butter, cheese, buckwheat noodles, and oat flour pancakes. So be prepared to pack on the pounds during your tour of the grasslands!

Whole Roasted Sheep (烤全羊)

In the past, this sumptuously meaty dish was a privilege reserved only for Mongolian royalty, since it was both expensive and complicated to cook. Nowadays, it is readily available throughout the restaurants and grasslands of Inner Mongolia. The main ingredient is unsurprisingly a whole sheep, which is filled with a mixture of spices before being baked in an airtight oven at high temperature for four to five hours.

In the past, this sumptuously meaty dish was a privilege reserved only for Mongolian royalty, since it was both expensive and complicated to cook. Nowadays, it is readily available throughout the restaurants and grasslands of Inner Mongolia. The main ingredient is unsurprisingly a whole sheep, which is filled with a mixture of spices before being baked in an airtight oven at high temperature for four to five hours.

Once the meat is medium to well-done, the carcass is removed from the oven and roasted over an open fire until it has turned a crispy golden-brown. The firewood used is typically from the apricot tree, as the smoke produced helps give the mutton its distinctive taste. After being roasted to perfection, the dish is served whole on a huge wooden platter. Custom dictates that, while the meat is being carved, a small triangular slice from the sheep’s head should be thrown in the fire as an offering. The two different cooking methods result in the mutton being mouth-wateringly crispy and flavourful, with meat so tender that it literally melts in your mouth.

Mongolian Hot Pot (涮羊肉)

Hot Pot may seem like an iconic Chinese dish, but it actually originated from Mongolia! Sometime during the Jin Dynasty (265-420), it became a popular way of eating meat such as beef, mutton, and horse among Mongolian herdsmen living on the northern grasslands, but it didn’t spread to southern China until the Song Dynasty (960-1279). While several regional variations developed throughout China, the Mongolian Hot Pot or “Instant-Boiled Mutton” remained the favourite of the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368) and is a popular dish in Inner Mongolia to this day.

Hot Pot may seem like an iconic Chinese dish, but it actually originated from Mongolia! Sometime during the Jin Dynasty (265-420), it became a popular way of eating meat such as beef, mutton, and horse among Mongolian herdsmen living on the northern grasslands, but it didn’t spread to southern China until the Song Dynasty (960-1279). While several regional variations developed throughout China, the Mongolian Hot Pot or “Instant-Boiled Mutton” remained the favourite of the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368) and is a popular dish in Inner Mongolia to this day.

According to local legend, the dish originated when Kublai Khan, the Khagan of the Mongol Empire and founding Emperor of the Yuan Dynasty, developed a sudden craving for stewed mutton. However, he happened to be in the middle of a battle and the enemy’s troops were fast approaching! In order to satiate his hunger, a chef deftly cut off a dozen thinly-sliced mutton strips and placed them in boiling water. As soon as the meat had browned, he swiftly removed it and put it in a bowl with a little salt. Kublai Khan devoured these mutton strips with glee before heading off to battle and achieving a grand victory. At the subsequent celebratory banquet, he requested that the chef prepare this mutton dish again and its status as a regional delicacy was cemented.

The dish consists of the choicest slices of mutton, cut from the back, rear legs, and tail of the sheep. Typically this raw mutton is served alongside tofu, Chinese cabbage, bean sprouts, and vermicelli. A pot of boiling soup is laid on a hot plate in the middle of the table, in which the raw ingredients are placed and left to cook. It is imperative that the mutton is removed as soon as it has browned. Each person is typically given a bowl containing a dipping sauce, which is made from sesame oil, chilli oil, spring onions, and soy sauce. Guests are then free to pick strips of the juicy mutton from the soup with their chopsticks and season them to taste.

Grabbing Mutton (手扒羊肉)

This traditional dish has been a favourite among Mongolian herdsmen for thousands of years, in part because it’s so deliciously simple! Meat from a freshly butchered sheep is first carved and then placed into a wok of boiling water with a little salt but no other seasonings. The mutton is thoroughly cooked but never allowed to over-boil, as this would make the meat tough and unpalatable. Once the mutton has browned nicely, it is removed from the water and should be eaten before it cools.

This traditional dish has been a favourite among Mongolian herdsmen for thousands of years, in part because it’s so deliciously simple! Meat from a freshly butchered sheep is first carved and then placed into a wok of boiling water with a little salt but no other seasonings. The mutton is thoroughly cooked but never allowed to over-boil, as this would make the meat tough and unpalatable. Once the mutton has browned nicely, it is removed from the water and should be eaten before it cools.

The name “grabbing mutton” derives from the fact that traditionally the mutton is eaten with the hands, kind of like barbecued spare ribs. If a local has treated you to this hearty dish, you must allow the host to select your piece of mutton for you, as customarily different parts are served to different guests. For example, the elderly are usually offered cuts from the leg and younger people will be given the ribs, while women get to enjoy the tender meat from the chest.

Roast Leg of Mutton (烤羊腿)

By now, you’ve probably noticed a pattern in the signature dishes of Inner Mongolia. We weren’t kidding when we said they loved mutton! Roast Leg of Mutton was supposedly a favourite of the infamous warlord Genghis Khan and is cooked in much the same way as Whole Roasted Sheep. A sheep’s leg is first scored across the skin before being seasoned with salt and placed on a tray with shredded carrot, celery, shallots, ginger, tomatoes, and peppers. The leg is then roasted in an oven for approximately 4 hours, until the skin has turned a rich golden-brown and the meat gives off an irresistible aroma. Nowadays this dish is a popular alternative to Whole Roasted Sheep, as it takes less time to cook and the leg is considered the tastiest part of the animal.

By now, you’ve probably noticed a pattern in the signature dishes of Inner Mongolia. We weren’t kidding when we said they loved mutton! Roast Leg of Mutton was supposedly a favourite of the infamous warlord Genghis Khan and is cooked in much the same way as Whole Roasted Sheep. A sheep’s leg is first scored across the skin before being seasoned with salt and placed on a tray with shredded carrot, celery, shallots, ginger, tomatoes, and peppers. The leg is then roasted in an oven for approximately 4 hours, until the skin has turned a rich golden-brown and the meat gives off an irresistible aroma. Nowadays this dish is a popular alternative to Whole Roasted Sheep, as it takes less time to cook and the leg is considered the tastiest part of the animal.

In fact, leaving an offering is such an integral part of the tradition surrounding ovoos that you’ll often find a variety of miscellaneous items underneath them, including old steering wheel covers, wooden crutches, empty liquor bottles, and even horses’ skulls! As modernity has crept in, these traditions have had to change, and it is now considered acceptable to honk your horn while passing an ovoo if you don’t have time to stop. While ovoos dedicated to the rich pantheon of deities in Mongolian shamanism tend to be for public use, those built for ancestral gods or village gods are often private shrines for a specific clan or shared by a certain village, banner, or league.

In fact, leaving an offering is such an integral part of the tradition surrounding ovoos that you’ll often find a variety of miscellaneous items underneath them, including old steering wheel covers, wooden crutches, empty liquor bottles, and even horses’ skulls! As modernity has crept in, these traditions have had to change, and it is now considered acceptable to honk your horn while passing an ovoo if you don’t have time to stop. While ovoos dedicated to the rich pantheon of deities in Mongolian shamanism tend to be for public use, those built for ancestral gods or village gods are often private shrines for a specific clan or shared by a certain village, banner, or league.

Historically, the ancestors of the Mongols were small nomadic tribes, such as the Xiongnu, the Xianbei, and the Donghu, who roamed the regions surrounding the Argun River sometime between the 5th and 3rd century BC. They remained largely separate until the beginning of the 13th century, when an enigmatic warrior loomed on the horizon and threatened to irrevocably change the course of history.

Historically, the ancestors of the Mongols were small nomadic tribes, such as the Xiongnu, the Xianbei, and the Donghu, who roamed the regions surrounding the Argun River sometime between the 5th and 3rd century BC. They remained largely separate until the beginning of the 13th century, when an enigmatic warrior loomed on the horizon and threatened to irrevocably change the course of history.