(303-439)

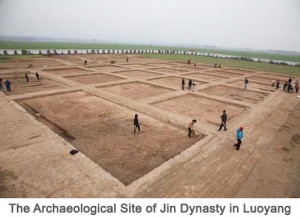

During a vicious civil war known as the War of the Eight Princes (301-305), the central government of the Jin Dynasty (265-420) was severely weakened and several chieftains from the northern tribes decided to seize this ample opportunity. They began a brutal rebellion known as the Wu Hu Uprising or the Uprising of the Five Barbarians (304-316), which decimated the Jin’s military forces and resulted in the imperial court losing control of northern China. Several Wu Hu warlords decided to establish their own dynasties during this time, including a powerful Xiongnu chieftain named Liu Yuan who founded the Former Zhao Dynasty (304–329). With no army to protect it, the imperial capital of Luoyang was left wide open and Liu Yuan’s son, Liu Cong, led his formidable army into the city in 311.

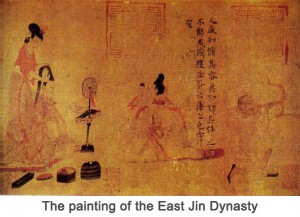

The reigning Emperor Huai was executed and, in a futile attempt to keep the dynasty alive, Sima Ye was enthroned as Emperor Min at the secondary capital of Chang’an (modern-day Xi’an). Yet the Liu clan were merciless. Liu Cong’s uncle, Liu Yao, stormed Chang’an in 216 and forced Emperor Min to surrender, bringing an end to the Western Jin Dynasty (265–316). While Sima Rui established the Eastern Jin Dynasty (317–420) from the safety of his southern capital in Jiankang (modern-day Nanjing), the north of China was under the sway of vicious Wu Hu warlords.

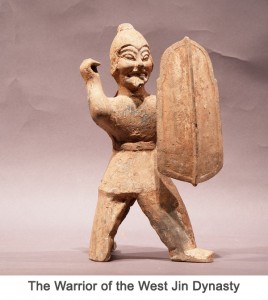

The term Wu Hu or “Five Barbarians” refers to several distinctly different ethnic groups that lived in China’s northern territories, the most prominent of which were the Xiongnu, Xianbei, Jie, Di, and Qiang. While the Xiongnu, Xianbei, and Jie people had once been pastoral nomads who hailed from the north, the Di and Qiang tribes were farmers and herders who had emigrated from the west. From the late Han Dynasty (206 BC–220 AD) onwards, they had settled in the north of China and had become increasingly Sinicized, meaning they were hardly the “savages” that many historians make them out to be. They had rebelled largely due to the increasing levels of discrimination that they faced from the oppressive Jin regime.

Like the Five Barbarians, the Sixteen Kingdoms is also something of a misnomer, as there were actually more than sixteen official kingdoms during this period and many of them never ran concurrently. The term was coined by the 6th century historian Cui Hong in his work The Spring and Autumn Annals of the Sixteen Kingdoms and refers to the following dynasties: the five Liangs (Former, Later, Northern, Southern, and Western); the four Yans (Former, Later, Northern, and Southern); the three Qins (Former, Later, and Western); the two Zhaos (Former and Later); the Cheng Han; and the Xia. Cui chose not to include several lesser kingdoms such as the Ran Wei, Zhai Wei, and Western Yan, as well as the Northern Wei Dynasty (386–535) because it eventually went on to unify northern China. Although several of these kingdoms were coexistent, many of them succeeded or subsumed one another.

Most of these northern states were founded by ethnic minority peoples and, as such, they faced a peculiar dilemma. Having come from a tribal institution that was not adapted to ruling a large agricultural society, they did not have the experience or the means within their own culture to effectively govern such a vast population. In order to combat this deficit, they had to make use of the traditional Chinese government structure, but this brought with it new dilemmas.

While the rulers themselves were of varying ethnicities, the wealthy nobility were invariably Han Chinese. In order for the foreign rulers to have any legitimacy with these powerful landowners, they had to conform to the complex rules of Chinese etiquette, heed the advice of Chinese scholars, and express themselves in terms of Chinese culture. How would they preserve their own cultural identity while also appeasing the Chinese aristocracy? It was a tension that very few of these short-lived kingdoms would survive. Rulers would either lose their cultural identity altogether and estrange themselves from their own people, or offend the Chinese nobles and lose invaluable support.

Fierce competition from the outside and internal political instability meant that these kingdoms ended as swiftly and violently as they began. This led to the Sixteen Kingdoms Period (303-439) becoming well-known as one of the most chaotic eras in Chinese history. Before the Northern Wei Dynasty, the Former Qin Dynasty (351–394) was the only one to successfully reunite the northern territories in 376. However, after a crushing defeat against the Eastern Jin Dynasty during the Battle of Fei River in 383, this dynasty eventually collapsed and caused even greater political fragmentation. After all, the higher you climb, the harder you fall!

It is therefore particularly significant that the Northern Wei Dynasty was the only one of these kingdoms to successfully unify northern China for a substantial period of time. The rulers of the Northern Wei, who were from the Tuoba clan of the Xianbei people, were profoundly Sinicized and even forbade the use of the Tuoba language, traditional dress, customs, and surnames during the late 5th century. It was this suppression of their unique cultural heritage that allowed them to effectively rule for such a long time, but at what cost? They may have attained great power, but they had alienated themselves from their own people. When they finally united northern China in 439, the Northern Wei ended the Sixteen Kingdoms Period and ushered in yet another tempestuous epoch in Chinese history known as the Northern and Southern Dynasties Period (420-589).

Although the Sixteen Kingdoms Period was one of great turbulence, it also represented the blossoming of Buddhist art and architecture. For example, the Former Qin Dynasty was responsible for the first grottoes that were carved in the Mogao Caves of Dunhuang; work on the Maijishan Grottoes near Tianshui began during the Later Qin Dynasty (384–417); the Bingling Temple Grottoes outside of Lanzhou were masterminded under the Western Qin Dynasty (385–431); and many of the grottoes found in the Hexi Corridor were the work of the Northern Liang Dynasty (397–460). With all of the fierce battles taking place around them, you could almost say that these grottoes were the real art of war!

东晋In a brutal rebellion known as the Wu Hu Uprising (304-316), the Jin Dynasty (265-420) was overrun by the northern tribal peoples and the north of China was lost. In 311, the imperial capital of Luoyang was captured and the reigning Emperor Huai was executed. In a desperate attempt to keep power, Sima Ye was enthroned as Emperor Min at the secondary capital of Chang’an (modern-day Xi’an) but to no avail; rebel forces stormed Chang’an in 316 and forced him to surrender. In short, this was one very unlucky decade for the Sima family! They lost their stranglehold on the north of China and the Western Jin Dynasty (265–316) officially collapsed. The invasion of nomads in the north prompted droves of people to emigrate south of the Yangtze River, and it seems this was where the salvation of the Jin Dynasty lay.

东晋In a brutal rebellion known as the Wu Hu Uprising (304-316), the Jin Dynasty (265-420) was overrun by the northern tribal peoples and the north of China was lost. In 311, the imperial capital of Luoyang was captured and the reigning Emperor Huai was executed. In a desperate attempt to keep power, Sima Ye was enthroned as Emperor Min at the secondary capital of Chang’an (modern-day Xi’an) but to no avail; rebel forces stormed Chang’an in 316 and forced him to surrender. In short, this was one very unlucky decade for the Sima family! They lost their stranglehold on the north of China and the Western Jin Dynasty (265–316) officially collapsed. The invasion of nomads in the north prompted droves of people to emigrate south of the Yangtze River, and it seems this was where the salvation of the Jin Dynasty lay.

During the latter 50 years of the Han Dynasty (206 BC–220 AD), political corruption, schismatic warlords, and violent rebellions ran rife. Wealthy families who had been forced to help the Emperor suppress the revolts secretly decided not to disband their military forces, and instead began amassing power outside of imperial authority. This set the scene for a sequence of epic clashes that would become legendary in Chinese history and would lead to the fractured Three Kingdoms Period.

During the latter 50 years of the Han Dynasty (206 BC–220 AD), political corruption, schismatic warlords, and violent rebellions ran rife. Wealthy families who had been forced to help the Emperor suppress the revolts secretly decided not to disband their military forces, and instead began amassing power outside of imperial authority. This set the scene for a sequence of epic clashes that would become legendary in Chinese history and would lead to the fractured Three Kingdoms Period.