When you look at Nanping, it’s hard to believe that this sleepy little village was once the site of two major battles, the home of the “10,000 silver purses”, and the backdrop for a handful of blockbuster movies. Yet there’s more to this rural slice of paradise than meets the eye! The nearby Nanping Mountain served as a battlefield during the Three Kingdoms Period (220-280 AD), but the area itself wouldn’t be settled until much later. Towards the end of the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368), the village was established by the Ye clan, who had immigrated there from nearby Qimen.

During the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), two other merchant families known as the Li and Cheng clans decided to settle in the village, which was a rarity as most villages were made up of just one clan during imperial times. And it seems that, though two may have been company, three was definitely a crowd in Nanping!

The success of these three families is often attributed to their competitiveness, as an abnormal number of villagers went on to become wealthy merchants, imperial officials, and learned scholars. Their accomplishments are living proof that a little healthy competition can go a long way! Throughout the Ming and Qing (1644-1912) dynasties, these families built glorious mansions, private schools, and ancestral halls as a testament to their fortune.

Their prosperity was so renowned that the 20 families living in the village came to be known as “the 10,000 silver purses”. Even the frequent peasant uprisings during the establishment of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom[1] (1851-1864) weren’t enough to shake the foundations of this tiny village. Unfortunately, when the Qing Dynasty finally collapsed and the imperial regime with it, the families in Nanping fell on hard times. Though their fortuitous streak may have been curtailed, their magnificent architecture was spared from damage by warfare and looting, and remains well-preserved as a monument to their former glory.

Their prosperity was so renowned that the 20 families living in the village came to be known as “the 10,000 silver purses”. Even the frequent peasant uprisings during the establishment of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom[1] (1851-1864) weren’t enough to shake the foundations of this tiny village. Unfortunately, when the Qing Dynasty finally collapsed and the imperial regime with it, the families in Nanping fell on hard times. Though their fortuitous streak may have been curtailed, their magnificent architecture was spared from damage by warfare and looting, and remains well-preserved as a monument to their former glory.

Nowadays the village is still inhabited by over 1,000 people from the Ye, Cheng, and Li clans, as well as a handful of outside families, and over 300 of its buildings date back to the Ming and Qing dynasties. These stunning mansions, with their white-washed walls and coal black roofs, are dotted throughout a maze of 72 lanes that zigzag throughout Nanping. A stretch of ancient woods, known as Wansonglin, surrounds the village and only adds to its mystical quality.

The village’s spectacular architecture is punctuated by eight ancestral halls, of which Xuzhi Hall and Kuiguang Hall are considered the most well-preserved. Both belong to the Ye family and, while Kuiguang Hall is an impressive 490 years old, Xuzhi Hall is a staggering 530 years old!

Xuzhi Hall is divided into three parts: the front hall, which was used for recreational activities; the main hall, which served as the centre for sacrificial ceremonies; and the back hall, where the memorial tablet to the ancestors is enshrined. This hall served as the main backdrop for the critically acclaimed film Ju Dou, directed by Zhang Yimou and starring the exceptional Gong Li. Many of the sets from the film have been maintained so, if you ever wanted to be in a movie, now’s your chance! Similarly Kuiguang Hall, with its smooth marble ornaments and elaborately decorated interior, was used as a set for the Oscar-winning film Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, directed by Ang Lee.

Xuzhi Hall is divided into three parts: the front hall, which was used for recreational activities; the main hall, which served as the centre for sacrificial ceremonies; and the back hall, where the memorial tablet to the ancestors is enshrined. This hall served as the main backdrop for the critically acclaimed film Ju Dou, directed by Zhang Yimou and starring the exceptional Gong Li. Many of the sets from the film have been maintained so, if you ever wanted to be in a movie, now’s your chance! Similarly Kuiguang Hall, with its smooth marble ornaments and elaborately decorated interior, was used as a set for the Oscar-winning film Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, directed by Ang Lee.

Other places of historical note include Banchun Garden, West Garden, and Baoyi Study. Banchun Garden was built during the Qing Dynasty by a wealthy merchant from the Ye family to serve as a private school for his children. The three spacious study rooms, half-moon shaped courtyard, and fragrant abundance of colourful flowers will make you wish you could go back to school! West Garden was also built as a study room but was tragically destroyed, leaving behind only a few ruins and a handful of multi-coloured peonies, plum trees, and towering bamboo grasses.

Yet by far the most poignant is the story of Baoyi Study, which was built by Li Huomei of the Li clan. Li had wanted to be a scholar but was only able to study for two years before he was forced to return home and work, as his family were very poor. He became a merchant, laboured diligently and eventually amassed a great fortune, which he used to build three private schools for the local children. As the old saying goes: “children are our future”!

[1] Taiping Heavenly Kingdom: An oppositional state in China that was formed from 1851 to 1864 and controlled some parts of southern China during the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912).

Make your dream trip to Nanping Village come true on our travel: Explore Traditional Culture in Picturesque Ancient Villages

Like the Wall Street stockbrokers of today, the Hui merchants were once renowned as some of the savviest businessmen in China. The term “Hui merchants” typically refers to any businessmen that hailed from the six counties of She, Xiuning, Qimen, Yixian, Jixi, and Wuyuan, which belonged to an ancient region known as Huizhou. Their rise to prosperity began during the Song Dynasty (960-1279), when the imperial capital was relocated from northern Kaifeng to the southern city of Lin’an (modern-day Hangzhou) in Zhejiang province. Since Huizhou was located in a focal place between the provinces of Jiangsu and Zhejiang, this meant that trade via road or river to the imperial capital was suddenly far more viable for the local people. In short, it was the capital that gave them capital!

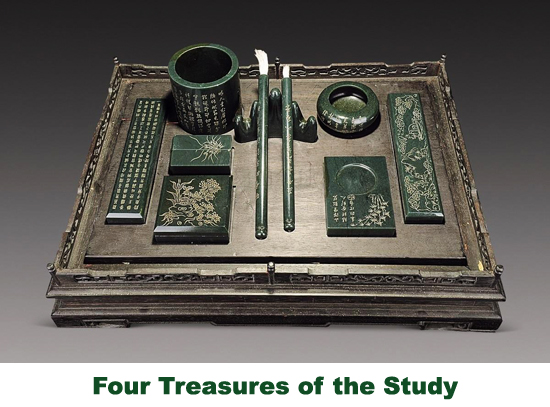

Like the Wall Street stockbrokers of today, the Hui merchants were once renowned as some of the savviest businessmen in China. The term “Hui merchants” typically refers to any businessmen that hailed from the six counties of She, Xiuning, Qimen, Yixian, Jixi, and Wuyuan, which belonged to an ancient region known as Huizhou. Their rise to prosperity began during the Song Dynasty (960-1279), when the imperial capital was relocated from northern Kaifeng to the southern city of Lin’an (modern-day Hangzhou) in Zhejiang province. Since Huizhou was located in a focal place between the provinces of Jiangsu and Zhejiang, this meant that trade via road or river to the imperial capital was suddenly far more viable for the local people. In short, it was the capital that gave them capital! After they had amassed a substantial fortune, they were able to open teahouses, restaurants, hotels, and pawnshops. During the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912), it was even rumoured that there wasn’t a single pawnbroker in China who wasn’t from Huizhou and that there was no place too far for Hui merchants to expand their business. They also began concentrating their efforts on manufacturing high quality goods, such as the “Four Treasures of the Study”. These four treasures, known as the writing brush, the Huizhou ink stick, the She ink slab, and Xuan paper, are still widely sold throughout the provinces of Anhui and Jiangxi to this day.

After they had amassed a substantial fortune, they were able to open teahouses, restaurants, hotels, and pawnshops. During the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912), it was even rumoured that there wasn’t a single pawnbroker in China who wasn’t from Huizhou and that there was no place too far for Hui merchants to expand their business. They also began concentrating their efforts on manufacturing high quality goods, such as the “Four Treasures of the Study”. These four treasures, known as the writing brush, the Huizhou ink stick, the She ink slab, and Xuan paper, are still widely sold throughout the provinces of Anhui and Jiangxi to this day. This may sound rather Machiavellian, but the Hui merchants were actually renowned for their strict moral code. They valued honesty and felt that cheating their customers would only damage profits in the long-term, as they would develop an unfavourable reputation. They ensured that their products were always of the best quality and refused to buy anything that they thought fell short of their exceptionally high standards. Once their wealth and fame had been established, many Hui merchants returned home to construct glorious mansions, ancestral temples, flourishing academies, decorative bridges, and towering archways to honour their ancestors. Yet these elegant constructions also proved to be part of their downfall.

This may sound rather Machiavellian, but the Hui merchants were actually renowned for their strict moral code. They valued honesty and felt that cheating their customers would only damage profits in the long-term, as they would develop an unfavourable reputation. They ensured that their products were always of the best quality and refused to buy anything that they thought fell short of their exceptionally high standards. Once their wealth and fame had been established, many Hui merchants returned home to construct glorious mansions, ancestral temples, flourishing academies, decorative bridges, and towering archways to honour their ancestors. Yet these elegant constructions also proved to be part of their downfall.

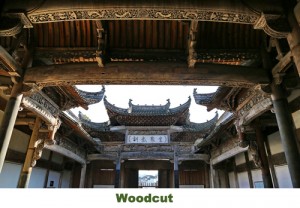

Once you’ve passed through the first three entrances of the temple, you’ll arrive at the magnificent Baolun Hall. It was originally built in 1542, during the Ming Dynasty, and is famed for its stunning murals, which have barely faded in spite of the fact that they are over 500 years old! Vivid sculptures of lions, clouds, and lotuses grace the façades of bluestone parapets, wooden eaves, and crossbeams. Ascending the wooden staircase to the attic, you’ll be treated with a breath-taking panoramic view of the village below and the lofty Mount Huang in the distance.

Once you’ve passed through the first three entrances of the temple, you’ll arrive at the magnificent Baolun Hall. It was originally built in 1542, during the Ming Dynasty, and is famed for its stunning murals, which have barely faded in spite of the fact that they are over 500 years old! Vivid sculptures of lions, clouds, and lotuses grace the façades of bluestone parapets, wooden eaves, and crossbeams. Ascending the wooden staircase to the attic, you’ll be treated with a breath-taking panoramic view of the village below and the lofty Mount Huang in the distance.

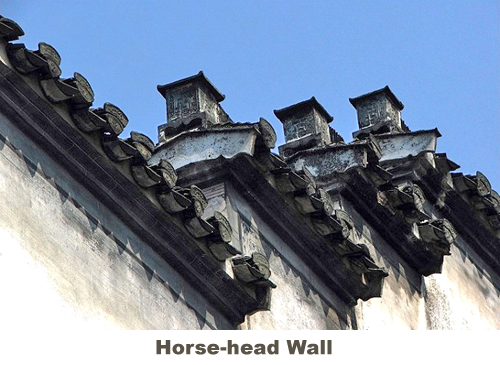

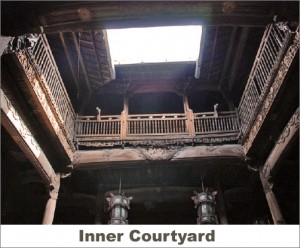

The outer wall of the compound is known as a “horse-head wall”, because it was said to resemble a horse’s head in shape. These high, crenelated walls were designed to separate Hui residences from each other, in order to prevent the spread of fire, to block out cold drafts, and to deter thieves. The roofs of all the buildings are constructed so that they incline towards the inner courtyard. Since the Hui merchants believed that water was a symbol of wealth, having all rainwater trickle into the inner courtyard symbolised the flow of wealth into the family. The rainwater would then collect in a large jar at the centre of the courtyard, which could be used in the event of a fire. Like true businessmen, the Hui merchant families never missed a trick!

The outer wall of the compound is known as a “horse-head wall”, because it was said to resemble a horse’s head in shape. These high, crenelated walls were designed to separate Hui residences from each other, in order to prevent the spread of fire, to block out cold drafts, and to deter thieves. The roofs of all the buildings are constructed so that they incline towards the inner courtyard. Since the Hui merchants believed that water was a symbol of wealth, having all rainwater trickle into the inner courtyard symbolised the flow of wealth into the family. The rainwater would then collect in a large jar at the centre of the courtyard, which could be used in the event of a fire. Like true businessmen, the Hui merchant families never missed a trick!

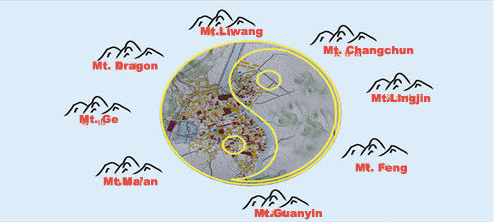

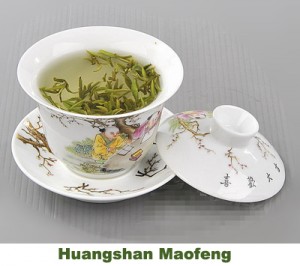

At 700 to 800 metres above sea level, the area around and on Huangshan Mountain, is the perfect place and main area of production for the superfine Huangshan Maofeng tea leaves. Huangshan Maofeng is produced in several different places on the mountain, including Peach Blossom Peak, Purple Cloud Peak, Cloud Valley Monastery, Pine Valley Temple and Hanging Bridge Temple. In fact, Huangshan Maofeng is produced throughout the whole Huizhou District. This region boasts a temperate climate and receives plenty of rainfall. The annual average temperature is between 15 to 16°C, and the average amount of precipitation is between 1,800 to 2,000 millimetres. The soil is deeply layered and made up of the yellow earth typically found in mountainous regions. This type of soil is loose in texture and has good water permeability. It contains an abundance of organic matter and phosphorus potassium, and it has an acidity level of between ph 4.5 and 5.5 which makes it suitable for the growth of tea trees.

At 700 to 800 metres above sea level, the area around and on Huangshan Mountain, is the perfect place and main area of production for the superfine Huangshan Maofeng tea leaves. Huangshan Maofeng is produced in several different places on the mountain, including Peach Blossom Peak, Purple Cloud Peak, Cloud Valley Monastery, Pine Valley Temple and Hanging Bridge Temple. In fact, Huangshan Maofeng is produced throughout the whole Huizhou District. This region boasts a temperate climate and receives plenty of rainfall. The annual average temperature is between 15 to 16°C, and the average amount of precipitation is between 1,800 to 2,000 millimetres. The soil is deeply layered and made up of the yellow earth typically found in mountainous regions. This type of soil is loose in texture and has good water permeability. It contains an abundance of organic matter and phosphorus potassium, and it has an acidity level of between ph 4.5 and 5.5 which makes it suitable for the growth of tea trees.

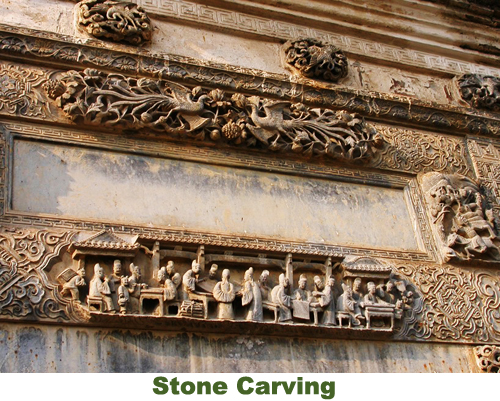

As a famous village in Huizhou, Xidi was once occupied by many rich Hui merchants. They wanted to build luxury houses to show off their wealth. But the strict hierarchy of society had restrictions on construction which specifically affected people of a lower social class. So the merchants were only able to choose the best materials and utilize the most sophisticated workmanship when building their place of residence. The memorial archway—built in 1578 by Hu Wenguang, who was a high-ranking official during the Ming Dynasty—is a good representation of the Hui-style of stone carving. The best example of Hui brick sculpture is in the house of another Ming official, which is in a place called the West Garden.

As a famous village in Huizhou, Xidi was once occupied by many rich Hui merchants. They wanted to build luxury houses to show off their wealth. But the strict hierarchy of society had restrictions on construction which specifically affected people of a lower social class. So the merchants were only able to choose the best materials and utilize the most sophisticated workmanship when building their place of residence. The memorial archway—built in 1578 by Hu Wenguang, who was a high-ranking official during the Ming Dynasty—is a good representation of the Hui-style of stone carving. The best example of Hui brick sculpture is in the house of another Ming official, which is in a place called the West Garden.