Like the Wall Street stockbrokers of today, the Hui merchants were once renowned as some of the savviest businessmen in China. The term “Hui merchants” typically refers to any businessmen that hailed from the six counties of She, Xiuning, Qimen, Yixian, Jixi, and Wuyuan, which belonged to an ancient region known as Huizhou. Their rise to prosperity began during the Song Dynasty (960-1279), when the imperial capital was relocated from northern Kaifeng to the southern city of Lin’an (modern-day Hangzhou) in Zhejiang province. Since Huizhou was located in a focal place between the provinces of Jiangsu and Zhejiang, this meant that trade via road or river to the imperial capital was suddenly far more viable for the local people. In short, it was the capital that gave them capital!

Like the Wall Street stockbrokers of today, the Hui merchants were once renowned as some of the savviest businessmen in China. The term “Hui merchants” typically refers to any businessmen that hailed from the six counties of She, Xiuning, Qimen, Yixian, Jixi, and Wuyuan, which belonged to an ancient region known as Huizhou. Their rise to prosperity began during the Song Dynasty (960-1279), when the imperial capital was relocated from northern Kaifeng to the southern city of Lin’an (modern-day Hangzhou) in Zhejiang province. Since Huizhou was located in a focal place between the provinces of Jiangsu and Zhejiang, this meant that trade via road or river to the imperial capital was suddenly far more viable for the local people. In short, it was the capital that gave them capital!

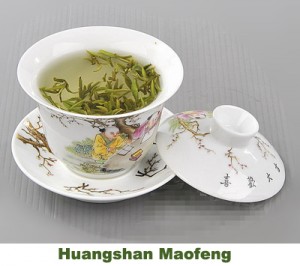

The shortage of fertile land in the region and the overabundance of manpower meant that many farmers in Huizhou simply became merchants because they needed to make ends meet. Little did they know that their legacy would echo through the ages! They were not skilled merchants and thus their success is all the more admirable, as it was primarily due to their painstaking efforts. Initially they engaged in the trade of almost any product they felt was profitable, including tea, grain, salt, silk, wood, and paint. Fortunately for them, Huizhou boasted the ideal climate for growing and producing several famous teas, including Huangshan Maofeng and Qimen Black Tea. By the end of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), over 70 per cent of the population in Huizhou was made up of merchants!

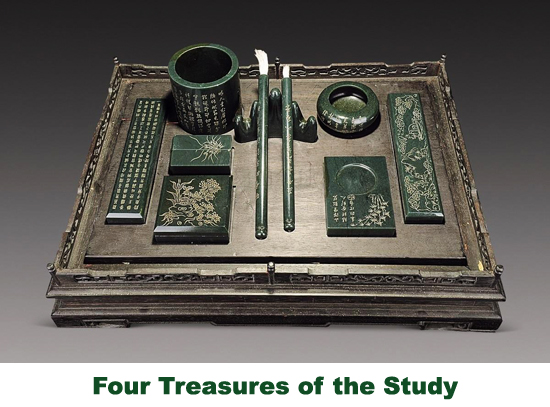

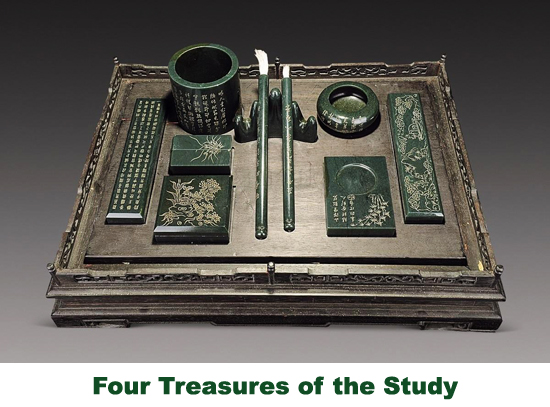

After they had amassed a substantial fortune, they were able to open teahouses, restaurants, hotels, and pawnshops. During the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912), it was even rumoured that there wasn’t a single pawnbroker in China who wasn’t from Huizhou and that there was no place too far for Hui merchants to expand their business. They also began concentrating their efforts on manufacturing high quality goods, such as the “Four Treasures of the Study”. These four treasures, known as the writing brush, the Huizhou ink stick, the She ink slab, and Xuan paper, are still widely sold throughout the provinces of Anhui and Jiangxi to this day.

After they had amassed a substantial fortune, they were able to open teahouses, restaurants, hotels, and pawnshops. During the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912), it was even rumoured that there wasn’t a single pawnbroker in China who wasn’t from Huizhou and that there was no place too far for Hui merchants to expand their business. They also began concentrating their efforts on manufacturing high quality goods, such as the “Four Treasures of the Study”. These four treasures, known as the writing brush, the Huizhou ink stick, the She ink slab, and Xuan paper, are still widely sold throughout the provinces of Anhui and Jiangxi to this day.

At the peak of their prosperity, they extended their influence east towards Jiangsu province, west to the provinces of Yunnan, Guizhou, and Gansu, north towards Liaoning province, and south to the provinces of Fujian and Guangdong. Once they had established their mercantile empire in China, they sailed forth to Japan, Thailand, and numerous Southeast Asian countries. It was said that their footsteps were left on almost half of the globe!

During this time, it was common for children of Hui merchants to begin their career as apprentices at the tender age of 13 and be doing business all over China by the age of 17. Talk about starting them young! They had achieved an almost mythical status, with the Hui Chronicle describing the average Hui merchant as “properly dressed, well-spoken, fully aware of price, knowing when is the good time to buy and sell, and getting extra profits from selling local goods in other places”. Unfortunately, there was one major downside to this otherwise profitable profession. According to traditional Confucian principles, merchants ranked as one of the lowest occupations in the social hierarchy.

In order to improve their social standing, many Hui merchant families invested in a good education for their children, so as to increase the possibility of them becoming scholars or government officials. Thanks to these venerable efforts, over 2,000 people from Huizhou passed the imperial examination and were able to obtain an official position during the Ming and Qing dynasties. This gave rise to a number of local sayings, such as “both father and son as ministers” or “three generations of imperial courtiers”. While these high ranking positions improved the social standing of the Hui merchant families, they also allowed these families to exert a considerable amount of political influence over the imperial government. After all, the long-term strategy of these families was to “provide funds for academic pursuits with business profits, get political positions through academic pursuits, and ensure business profits from the political positions”.

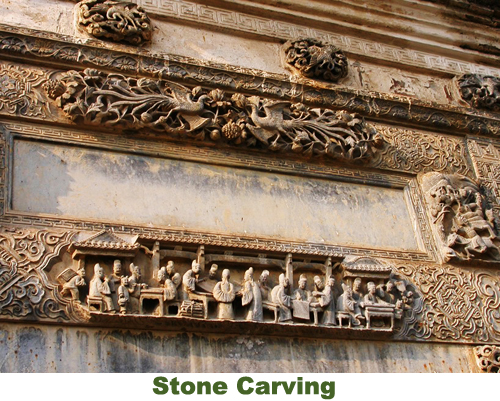

This may sound rather Machiavellian, but the Hui merchants were actually renowned for their strict moral code. They valued honesty and felt that cheating their customers would only damage profits in the long-term, as they would develop an unfavourable reputation. They ensured that their products were always of the best quality and refused to buy anything that they thought fell short of their exceptionally high standards. Once their wealth and fame had been established, many Hui merchants returned home to construct glorious mansions, ancestral temples, flourishing academies, decorative bridges, and towering archways to honour their ancestors. Yet these elegant constructions also proved to be part of their downfall.

This may sound rather Machiavellian, but the Hui merchants were actually renowned for their strict moral code. They valued honesty and felt that cheating their customers would only damage profits in the long-term, as they would develop an unfavourable reputation. They ensured that their products were always of the best quality and refused to buy anything that they thought fell short of their exceptionally high standards. Once their wealth and fame had been established, many Hui merchants returned home to construct glorious mansions, ancestral temples, flourishing academies, decorative bridges, and towering archways to honour their ancestors. Yet these elegant constructions also proved to be part of their downfall.

As the Qing Dynasty collapsed and imperial rule in China came to an end, the Hui merchants lost their monopoly on the salt trade, as this had been enforced by the imperial government. Instead of investing their money in improving their other business ventures, the Hui merchants had spent it on their lavish mansions, meaning they were unable to compete with foreign factories that had adopted new technologies and become more streamlined. While China began to embrace modernity, this tragically sounded the death knell for the Hui merchants. Nowadays, all that remains of their illustrious legacy are the stunning works of architecture that they left behind.

Join a travel with us to discover more stories about Hui Merchants: Explore the Ancient Chinese Villages in the Huizhou Region and Explore Chinese Culture through the Ages

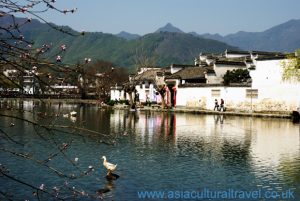

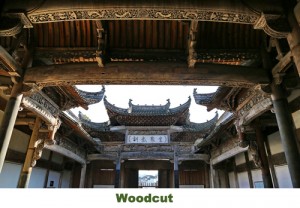

The scenic village of Lucun is just one kilometre (0.6 mi) north of Hongcun village, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and matches it in both artistry and beauty. The village was originally established during the late Tang Dynasty (618-907), although much of its magnificent architecture dates back to the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1912) dynasties. Of the more than 140 stunningly well-preserved buildings dotted throughout Lucun, Zhicheng Hall is considered the most spectacular.

The scenic village of Lucun is just one kilometre (0.6 mi) north of Hongcun village, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and matches it in both artistry and beauty. The village was originally established during the late Tang Dynasty (618-907), although much of its magnificent architecture dates back to the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1912) dynasties. Of the more than 140 stunningly well-preserved buildings dotted throughout Lucun, Zhicheng Hall is considered the most spectacular.

Like the Wall Street stockbrokers of today, the Hui merchants were once renowned as some of the savviest businessmen in China. The term “Hui merchants” typically refers to any businessmen that hailed from the six counties of She, Xiuning, Qimen, Yixian, Jixi, and Wuyuan, which belonged to an ancient region known as Huizhou. Their rise to prosperity began during the Song Dynasty (960-1279), when the imperial capital was relocated from northern Kaifeng to the southern city of Lin’an (modern-day Hangzhou) in Zhejiang province. Since Huizhou was located in a focal place between the provinces of Jiangsu and Zhejiang, this meant that trade via road or river to the imperial capital was suddenly far more viable for the local people. In short, it was the capital that gave them capital!

Like the Wall Street stockbrokers of today, the Hui merchants were once renowned as some of the savviest businessmen in China. The term “Hui merchants” typically refers to any businessmen that hailed from the six counties of She, Xiuning, Qimen, Yixian, Jixi, and Wuyuan, which belonged to an ancient region known as Huizhou. Their rise to prosperity began during the Song Dynasty (960-1279), when the imperial capital was relocated from northern Kaifeng to the southern city of Lin’an (modern-day Hangzhou) in Zhejiang province. Since Huizhou was located in a focal place between the provinces of Jiangsu and Zhejiang, this meant that trade via road or river to the imperial capital was suddenly far more viable for the local people. In short, it was the capital that gave them capital! After they had amassed a substantial fortune, they were able to open teahouses, restaurants, hotels, and pawnshops. During the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912), it was even rumoured that there wasn’t a single pawnbroker in China who wasn’t from Huizhou and that there was no place too far for Hui merchants to expand their business. They also began concentrating their efforts on manufacturing high quality goods, such as the “Four Treasures of the Study”. These four treasures, known as the writing brush, the Huizhou ink stick, the She ink slab, and Xuan paper, are still widely sold throughout the provinces of Anhui and Jiangxi to this day.

After they had amassed a substantial fortune, they were able to open teahouses, restaurants, hotels, and pawnshops. During the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912), it was even rumoured that there wasn’t a single pawnbroker in China who wasn’t from Huizhou and that there was no place too far for Hui merchants to expand their business. They also began concentrating their efforts on manufacturing high quality goods, such as the “Four Treasures of the Study”. These four treasures, known as the writing brush, the Huizhou ink stick, the She ink slab, and Xuan paper, are still widely sold throughout the provinces of Anhui and Jiangxi to this day. This may sound rather Machiavellian, but the Hui merchants were actually renowned for their strict moral code. They valued honesty and felt that cheating their customers would only damage profits in the long-term, as they would develop an unfavourable reputation. They ensured that their products were always of the best quality and refused to buy anything that they thought fell short of their exceptionally high standards. Once their wealth and fame had been established, many Hui merchants returned home to construct glorious mansions, ancestral temples, flourishing academies, decorative bridges, and towering archways to honour their ancestors. Yet these elegant constructions also proved to be part of their downfall.

This may sound rather Machiavellian, but the Hui merchants were actually renowned for their strict moral code. They valued honesty and felt that cheating their customers would only damage profits in the long-term, as they would develop an unfavourable reputation. They ensured that their products were always of the best quality and refused to buy anything that they thought fell short of their exceptionally high standards. Once their wealth and fame had been established, many Hui merchants returned home to construct glorious mansions, ancestral temples, flourishing academies, decorative bridges, and towering archways to honour their ancestors. Yet these elegant constructions also proved to be part of their downfall.

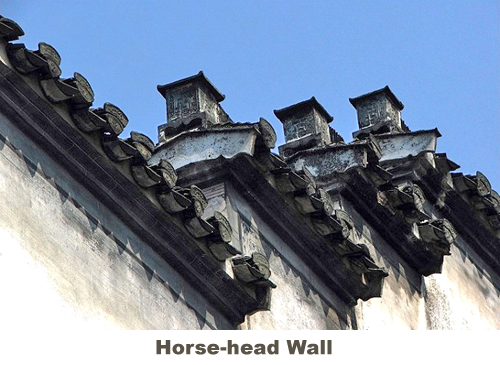

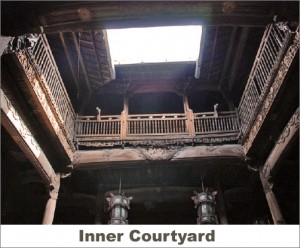

The outer wall of the compound is known as a “horse-head wall”, because it was said to resemble a horse’s head in shape. These high, crenelated walls were designed to separate Hui residences from each other, in order to prevent the spread of fire, to block out cold drafts, and to deter thieves. The roofs of all the buildings are constructed so that they incline towards the inner courtyard. Since the Hui merchants believed that water was a symbol of wealth, having all rainwater trickle into the inner courtyard symbolised the flow of wealth into the family. The rainwater would then collect in a large jar at the centre of the courtyard, which could be used in the event of a fire. Like true businessmen, the Hui merchant families never missed a trick!

The outer wall of the compound is known as a “horse-head wall”, because it was said to resemble a horse’s head in shape. These high, crenelated walls were designed to separate Hui residences from each other, in order to prevent the spread of fire, to block out cold drafts, and to deter thieves. The roofs of all the buildings are constructed so that they incline towards the inner courtyard. Since the Hui merchants believed that water was a symbol of wealth, having all rainwater trickle into the inner courtyard symbolised the flow of wealth into the family. The rainwater would then collect in a large jar at the centre of the courtyard, which could be used in the event of a fire. Like true businessmen, the Hui merchant families never missed a trick!

At 700 to 800 metres above sea level, the area around and on Huangshan Mountain, is the perfect place and main area of production for the superfine Huangshan Maofeng tea leaves. Huangshan Maofeng is produced in several different places on the mountain, including Peach Blossom Peak, Purple Cloud Peak, Cloud Valley Monastery, Pine Valley Temple and Hanging Bridge Temple. In fact, Huangshan Maofeng is produced throughout the whole Huizhou District. This region boasts a temperate climate and receives plenty of rainfall. The annual average temperature is between 15 to 16°C, and the average amount of precipitation is between 1,800 to 2,000 millimetres. The soil is deeply layered and made up of the yellow earth typically found in mountainous regions. This type of soil is loose in texture and has good water permeability. It contains an abundance of organic matter and phosphorus potassium, and it has an acidity level of between ph 4.5 and 5.5 which makes it suitable for the growth of tea trees.

At 700 to 800 metres above sea level, the area around and on Huangshan Mountain, is the perfect place and main area of production for the superfine Huangshan Maofeng tea leaves. Huangshan Maofeng is produced in several different places on the mountain, including Peach Blossom Peak, Purple Cloud Peak, Cloud Valley Monastery, Pine Valley Temple and Hanging Bridge Temple. In fact, Huangshan Maofeng is produced throughout the whole Huizhou District. This region boasts a temperate climate and receives plenty of rainfall. The annual average temperature is between 15 to 16°C, and the average amount of precipitation is between 1,800 to 2,000 millimetres. The soil is deeply layered and made up of the yellow earth typically found in mountainous regions. This type of soil is loose in texture and has good water permeability. It contains an abundance of organic matter and phosphorus potassium, and it has an acidity level of between ph 4.5 and 5.5 which makes it suitable for the growth of tea trees.