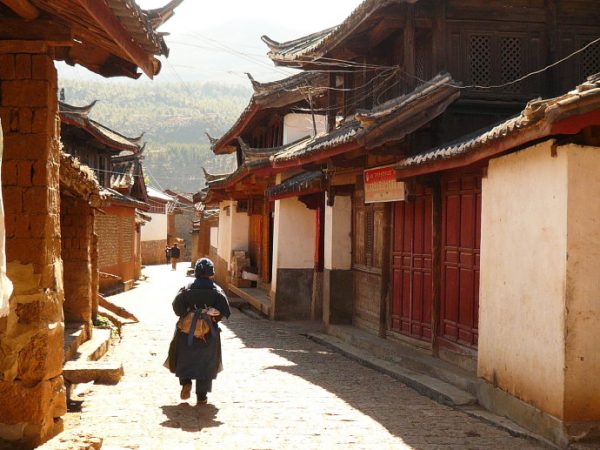

As the Three Pagodas rise up through the mist on a cool spring morning in Dali, the people of old town wake up not to the roar of engines or the clamour of construction work, but to the peaceful pitter-patter of feet on flagstone streets and sweet chirping of birds. As an act of preservation, the local government banned the construction of new buildings and the use of motor vehicles in the ancient part of Dali, so it has remained truly unchanged since it was rebuilt in the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644). Tragically much of the original city was lost when the Mongolians overthrew the Kingdom of Dali in 1253, but parts of the ancient capital still remain and are complemented beautifully by the perfectly preserved Ming-style architecture.

The ancient town is fast becoming one of the most popular destinations for foreign tourists and is speedily adapting to this end. The town itself exhibits wonderful examples of Ming-style architecture, from the elaborately carved eaves of the roofs through to the characteristically white-washed walls. It is also one of the few places where you can witness the traditional architecture of the Bai ethnic minority. The Bai people make up over 65% of Dali’s population at prefecture level and, with the multitude of Bai tearooms, batik[1] stores and homes scattered throughout the city, they certainly make their presence known.

Bai houses consist of three rooms: one main room and two side rooms. Facing the main room, there is always a wall called the “shining wall”. It is so called because, when the sun sets, the sunlight shining on the wall is reflected into the courtyard, thus brightening up the whole house. Bai people love to decorate their homes, so these traditional houses are flush with colourful paintings, woodcarvings, marble ornaments, and Bai batik cloth. Walking into a Bai household can feel like entering a precious art exhibition; it all looks so beautiful but you’re too scared to touch anything!

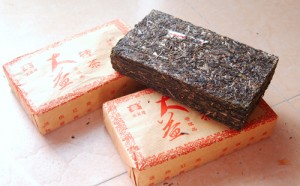

There are a number of Bai teahouses dotted throughout the old town where you can take part in the traditional Three Cups of Tea ceremony. First, you must drink one cup of bitter tea, then one cup of sweet tea, and finally one cup of aftertaste tea. The first represents suffering, the second represents the success and happiness that comes after hardship and the third represents reflection on the past. However, to the weary traveller they may all just represent a relaxing cup of tea!

If you fancy testing out your Chinese or your haggling skills, Yu’er Road hosts a plethora of antique and craftwork shops that are all placed very close together. You could easily spend a whole day browsing through all of the antiques, Bai batik works and Miao embroidered clothes on offer. However, the most marvellous souvenirs are the ornaments made from Dali marble. Dali is famous throughout China for its many types of marble, which are used both in construction and for decorative objects. This marble is so famous that the Chinese word for marble, “dàlǐ shí” (大理石), literally means “Dali stone”. Some of the larger and more complex marble ornaments fetch prices of up to 10,000 yuan (about £1,000), so choose wisely or you may not have any money left for your flight home!

The town has become particularly famous for its Yangren or “Foreigners” Street, which is lined with some of the most vibrant Western-style cafés, restaurants, and bars that the city has to offer. Many of these establishments are run by foreigners who have chosen to settle in Dali, making them the perfect place to meet other backpackers and take a break from the Chinese way of life. There are plenty of hotels and hostels scattered throughout the old town, so you’ll never be at a loss if you want to get away from the commotion of the city’s modern district. The simple, old-fashioned way of life in Dali Ancient Town is what draws so many people here, and the city itself, surrounded by verdant mountains and shimmering lakes, is what makes them stay.

[1] Batik: A cloth-dying process whereby a knife that has been dipped in hot wax is used to draw a pattern onto the cloth. The cloth is then boiled in dye, which melts the wax. Once the wax has melted off, the cloth is removed from the boiling dye. The rest of the cloth will be coloured by the dye but the pattern under the wax will have remained the original colour of the cloth.