Much like the environment in which they live, the customs of the Tibetan ethnic minority are marked by their elegance, solemnity, and deep spirituality. This is most often seen in the traditions surrounding a ceremonial white scarf, known as a hada[1]. The hada features in both traditional Tibetan and Mongolian culture, but plays a vastly different role in each. In Tibet, it evolved out of the ancient custom of adorning statues of deities with clothes. The white hada symbolises purity, faithfulness, and respect to the receiver. It is a common courtesy afforded to everyone, no matter their rank or background.

The hada itself is made of loosely woven silk and features a range of patterns, which have auspicious or symbolic meanings. They can be as short as 50 centimetres (20 in) and as long as 4 metres (13 ft.). While most hada are white, there is a special version that is made up of five different colours: blue to represent the air; white to symbolise water; yellow to signify the earth; green to denote nature; and red to indicate fire. This five-coloured hada is considered to be the cloth of the Buddha and, as such, it must only be given on exceedingly important occasions. It is a highly valued gift that is exclusively offered to statues of the Buddha, eminent monks, or intimate relatives.

The white hada is customarily offered during a variety of occasions, from regular greetings and temple visits to marriage ceremonies and funerals. In some cases, Tibetans will even leave behind a hada near their seat in a temple to signify that, although they have physically left, their heart remains. When presenting a hada, the giver typically takes the scarf in both hands, lifts it to the shoulder height of the recipient, extends their arms, bends over, and passes it to the recipient, taking care to ensure that their head is level with the hada. To show respect, the recipient should accept the hada with both hands. It is also considered acceptable to place the hada around someone’s neck if they are your social peers or juniors, but seniors or elders should have the hada placed in front of their seats or at their feet as a mark of deference.

The practice of giving hada is so centric to Tibetan culture that, whenever a person leaves the house, they will carry several hada with them in case an opportunity arises where they might be expected to offer one. When writing letters, they will even enclose a miniature hada in the envelope! In most contexts, the hada is designed to extend good wishes and respect, but its significance may change slightly depending on the context. During festivals, a hada is exchanged to wish the recipient a happy holiday. At weddings, the bride and groom are presented with hada in the hopes that they will have everlasting harmony and a bright future together. At funerals, the family present hada to the guests so that the Buddha may bless them and the guests offer hada to the grieving relatives in order to express their condolences.

The practice of giving hada is so centric to Tibetan culture that, whenever a person leaves the house, they will carry several hada with them in case an opportunity arises where they might be expected to offer one. When writing letters, they will even enclose a miniature hada in the envelope! In most contexts, the hada is designed to extend good wishes and respect, but its significance may change slightly depending on the context. During festivals, a hada is exchanged to wish the recipient a happy holiday. At weddings, the bride and groom are presented with hada in the hopes that they will have everlasting harmony and a bright future together. At funerals, the family present hada to the guests so that the Buddha may bless them and the guests offer hada to the grieving relatives in order to express their condolences.

Aside from the hada, there is a strict etiquette in Tibetan culture surrounding the act of greeting. When visiting relatives, it is customary for the visitor to carry a basket filled with gifts, a thermos flask of buttered tea, and a bucket full of chang[2]. The basket should be covered with a cloth to ensure that no one can see inside. When the guest arrives, the host and hostess will welcome them warmly before enjoying a drink of the butter tea and the chang they have brought.

After a long time spent chatting and catching up, the guest will finally present the host with their gift-basket. It is considered polite for the host to leave some of the gifts, such as food, within the basket for the guest to take back home, as this shows modesty and restraint. Not only that, but the host will be expected to add some inexpensive items to the basket, such as fresh vegetables, fresh fruit, or new clothes for the guest’s children. Most importantly of all, the host will take note of what the guest has brought so that, when they pay a visit, they can bring a gift-basket of similar value. Unlike most people, who give so that they can later receive, the Tibetans receive so that they can give!

Superstition is also a prominent feature of Tibetan culture, with numerous taboos and omens being observed. A traveller who passes by a funeral procession, a source of running water, or a person carrying a pitcher of water is said to have good luck coming their way. A vulture or owl perched on a rooftop is a sign that death or misfortune will soon befall the inhabitants. Snowfall during a wedding is believed to be a sign that the newlyweds will face many difficulties in their marriage. By contrast, snowfall during a funeral means that the family will not suffer another death for a long time. In short, don’t dream of a white wedding, wish for a white funeral!

[1] Hada: A hada is a narrow strip of silk or cotton that is used by Mongolian and Tibetan people as a greeting gift. Although it has little monetary value, in a nomadic culture it carries deep symbolic value, as everything must be carried on one’s person and therefore must be deemed worthy to take up precious limited space.

[2] Chang: Chang is an alcoholic beverage brewed from highland barley, millet, or rice grains. It is popular among the Tibetan and Nepalese people. Although its alcohol content is low, it produces a warming sensation that is ideal in the frozen climes of Tibet and Nepal.

Living primarily in isolated locations throughout India, Nepal, Bhutan, and the Tibet Autonomous Region of China, the Tibetan people have maintained an air of mystery that has captured the curiosity of people throughout the world. They embody a culture defined by spirituality, communion with nature, and rigid discipline. Even their language is highly stylised, with honorific and ordinary versions for most words, which are used to address superiors or inferiors respectively. The indisputable importance that religion holds for Tibetans is reflected in this language, as there is a set of higher honorific terms that are only to be used when addressing the highest sect of Buddhist lamas.

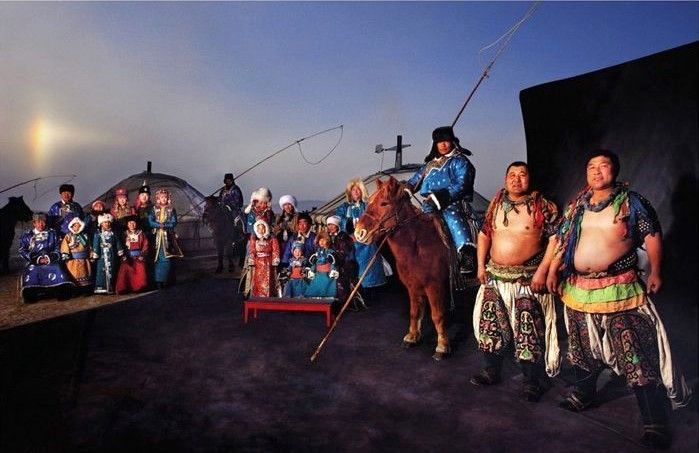

Living primarily in isolated locations throughout India, Nepal, Bhutan, and the Tibet Autonomous Region of China, the Tibetan people have maintained an air of mystery that has captured the curiosity of people throughout the world. They embody a culture defined by spirituality, communion with nature, and rigid discipline. Even their language is highly stylised, with honorific and ordinary versions for most words, which are used to address superiors or inferiors respectively. The indisputable importance that religion holds for Tibetans is reflected in this language, as there is a set of higher honorific terms that are only to be used when addressing the highest sect of Buddhist lamas. In spite of the hostile environment in which they live, the traditional garments of the Tibetan people are defined by their bright colours and elaborate ornamentation. Like precious stones and glimmering jewels, they stand out on the barren plains of the Tibetan plateau. Tibetans typically don long-sleeved jackets made of silk or cloth, covered by a loose robe tied at the right by a band. Nomadic herdsmen and women working in colder climates eschew the jacket in favour of sheepskin robes fringed with fur. While women tend to wear skirts with a multi-coloured apron over top and men wear trousers, they both opt for leather long-boots to combat the rocky terrain and felt or fur hats to keep themselves warm. For the sake of mobility, many Tibetans leave one or both shoulders uncovered and tie the sleeves around their waist when they are working.

In spite of the hostile environment in which they live, the traditional garments of the Tibetan people are defined by their bright colours and elaborate ornamentation. Like precious stones and glimmering jewels, they stand out on the barren plains of the Tibetan plateau. Tibetans typically don long-sleeved jackets made of silk or cloth, covered by a loose robe tied at the right by a band. Nomadic herdsmen and women working in colder climates eschew the jacket in favour of sheepskin robes fringed with fur. While women tend to wear skirts with a multi-coloured apron over top and men wear trousers, they both opt for leather long-boots to combat the rocky terrain and felt or fur hats to keep themselves warm. For the sake of mobility, many Tibetans leave one or both shoulders uncovered and tie the sleeves around their waist when they are working.

Historically, the ancestors of the Mongols were small nomadic tribes, such as the Xiongnu, the Xianbei, and the Donghu, who roamed the regions surrounding the Argun River sometime between the 5th and 3rd century BC. They remained largely separate until the beginning of the 13th century, when an enigmatic warrior loomed on the horizon and threatened to irrevocably change the course of history.

Historically, the ancestors of the Mongols were small nomadic tribes, such as the Xiongnu, the Xianbei, and the Donghu, who roamed the regions surrounding the Argun River sometime between the 5th and 3rd century BC. They remained largely separate until the beginning of the 13th century, when an enigmatic warrior loomed on the horizon and threatened to irrevocably change the course of history.