Great red orbs illuminate the night sky, floating off into the distance as the full moon rises like a pearl in a sea of darkness. Each one carries the wishes, desires, and dreams of an individual, all dancing their way up to the heavens in the hopes of bringing their owners good fortune. Lanterns, those great beacons of traditional art, have become synonymous with Chinese culture. Cut from paper; carved from wood; chipped from jade; these radiant decorations are as varied as they are charming. And what better time to admire them than during the magnificent Lantern Festival?

Also known as the Yuanxiao Festival, the First Full Moon Festival, and the Shangyuan Festival, this time-honoured tradition falls on the 15th day of the first month according to the Chinese lunar calendar. This means it normally lands sometime during February or March according to our Gregorian calendar. The holiday itself falls on the night of the first full moon and marks the end of the Spring Festival or Chinese New Year period. With that in mind, you can see why the Chinese people would want their most treasured festival to go out with bang!

In Hong Kong, it is regarded as the Chinese equivalent of Valentine’s Day because, in ancient times, it was one of the few occasions where single men and women would be allowed to go out in the evening and mingle freely. Although it has lost this association throughout much of mainland China, the lonely hearts of Hong Kong still hold out hope that they’ll light a fire under more than just a lantern!

Customs

Customs related to the Lantern Festival are innumerable and varied. Folk traditions such as firework displays, lion dances, dragon dances, and stilt-walking all feature prominently, making this one of the most vibrant festivals in the Chinese canon. However, three main activities dominate the celebrations: the lighting of lanterns, the guessing of lantern riddles, and the eating of delicious tangyuan.

Over time, the colourful lanterns have become increasingly more complex and artistic, allowing artisans to showcase their unique talents. Nowadays, for safety reasons, most of them are lit using electric or neon lighting. In some cities, such as Chengdu in Sichuan province, fairs will be held where colossal lanterns in the shape of zodiac animals or figures from Chinese folklore are erected for the enjoyment of the public.

Yet some of these lanterns aren’t just for decoration! Throughout China, large groups of them will be strung up together in public parks and have small strips of paper pasted inside of them. Each piece of paper is inscribed with a riddle and locals will gather under the lanterns in order to solve them. If you think you’ve cracked one, you must take the piece of paper, find the person who wrote the riddle, and tell them your answer. Correct answers earn you a small prize, while incorrect ones mean that, like the lanterns, you’ll be hung out to dry!

Yet some of these lanterns aren’t just for decoration! Throughout China, large groups of them will be strung up together in public parks and have small strips of paper pasted inside of them. Each piece of paper is inscribed with a riddle and locals will gather under the lanterns in order to solve them. If you think you’ve cracked one, you must take the piece of paper, find the person who wrote the riddle, and tell them your answer. Correct answers earn you a small prize, while incorrect ones mean that, like the lanterns, you’ll be hung out to dry!

If you don’t get a prize, then a hearty bowl of tangyuan is sure to cheer you up! This traditional festival food, known as yuanxiao in the north of China, is a type of glutinous rice ball that can be served plain or with filling. The Chinese people believe the round shape of these balls and the bowls they are served in symbolise family togetherness. Even the name tangyuan, which is a homophone for “tuanyuan” or “union”, suggests harmony. In short, a family who eats tangyuan together, stays together!

In the south of China, tangyuan are made by hand, with the glutinous rice being moulded into a flat circle before being wrapped around the filling. Tangyuan are usually much softer than northern yuanxiao and come in sweet and savoury varieties, with the savoury tangyuan typically being stuffed with salty fillings like minced meat and vegetables. In the north, yuanxiao are made by taking balls of filling and rolling them in wet, powdered glutinous rice until they become fully coated. They only come in sweet varieties, with fillings like red bean paste, sesame paste, jujube paste, walnut butter, or peanut butter. Depending on personal preference, these squishy treats can be boiled, fried, or steamed. The sweet version is often served in a syrupy soup, while the savoury variety comes in a clear broth.

History

The decorated history of the Lantern Festival starts as far back as the Han Dynasty (206 BC–220 AD), although its origins are unclear. Some people believe it is connected to Taiyi, who was regarded as the God of Heaven in ancient times and was believed to have omnipotent control of the human world. According to legend, he commanded an army of sixteen fearsome dragons, who would inflict drought, storms, famine, or pestilence on mankind at his beck and call. The first emperor, Qin Shi Huang, would honour him every year with splendid ceremonies so that he would bestow good weather and good health on the people. During the Han Dynasty, Emperor Wu paid special attention to this annual event and, in 104 BC, he marked it as an official festival of great significance, declaring that its ceremonies would last throughout the night. It was these religious ceremonies that eventually became the basis for the Lantern Festival.

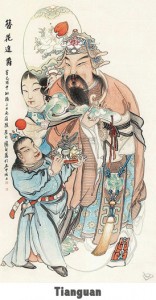

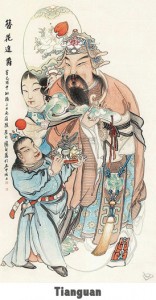

Alternatively, others attribute the festival to a Taoist deity named Tianguan. Tianguan was the official of heaven who bestowed good fortune on people, and his birthday fell on the 15th day of the first lunar month. It was believed that this benevolent god enjoyed all kinds of entertainment, so worshipers would prepare a myriad of activities for his birthday as a way to pray for his good favour. After all, you can’t have a godly birthday without a party of epic proportions! This is where the name Shangyuan Festival came from, as the term “shangyuan” (上元) in Taoist philosophy denoted the time period surrounding this deity’s birthday (i.e. Spring).

Alternatively, others attribute the festival to a Taoist deity named Tianguan. Tianguan was the official of heaven who bestowed good fortune on people, and his birthday fell on the 15th day of the first lunar month. It was believed that this benevolent god enjoyed all kinds of entertainment, so worshipers would prepare a myriad of activities for his birthday as a way to pray for his good favour. After all, you can’t have a godly birthday without a party of epic proportions! This is where the name Shangyuan Festival came from, as the term “shangyuan” (上元) in Taoist philosophy denoted the time period surrounding this deity’s birthday (i.e. Spring).

By the Tang Dynasty (618-907), this festival had developed into a 3-day long affair and the Emperor had lifted the traditional curfew, meaning civilians were allowed to enjoy the lantern displays throughout the day and night. During the Song Dynasty (960-1279), celebrations were extended over a 5-day period and the custom of writing riddles on lanterns had emerged. The Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) extended it to a whopping 10-day long extravaganza, although it was curtailed back to 3 days by the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912). However, it was during the Qing Dynasty that the festival’s popularity really started booming, as fireworks became a staple part of the celebrations.

Legends

With a history that stretches back over 2,000 years, it’s unsurprising that the Lantern Festival has accrued as many origin stories as there are lanterns in the sky! Each one is as diverse as the next, and they are all endowed with a peculiar charm unique to Chinese tales. One of the chief legends concerns the great Tiandi, who was the first god according to Chinese folk religion. One day, a heavenly crane descended to earth and was accidentally killed by a villager. Tiandi was enraged, as this crane had been one of his favourites. He decided that, on the 15th day of the first lunar month, he would send an army to burn the village to the ground. His daughter heard about his plan and decided to warn the villagers, who were all at a loss as to what to do.

It was then that a wise old man came forward and suggested that the villagers hang red lanterns outside of their houses, light bonfires in the streets, and set off firecrackers. He said that, from the heavenly realm, this would give the village the appearance of being on fire and hopefully fool Tiandi. Lo and behold, on the 15th lunar day, Tiandi’s army arrived and were baffled by what they saw. From above, it was clear that the village was ablaze, so they returned to Tiandi and informed him that the village had already been destroyed. Thus the village was spared and, from that day onwards, people celebrated the occasion by carrying lanterns and setting off fireworks.

Another popular legend involves a maiden named Yuan-Xiao, who supposedly worked in the imperial palace during the Han Dynasty. One cold winter’s day, the Emperor’s favourite adviser, Dongfang Shuo, was strolling through the imperial gardens when he came across Yuan-Xiao, who was weeping and preparing to throw herself into a well. Dongfang asked her why she wanted to end her life and Yuan-Xiao told him that she hadn’t seen her family since she had started working in the palace. If she couldn’t show her filial piety in this life, she would rather die. Dongfang was a kind man and said that, if she promised not to kill herself, he would find a way to reunite her with her family.

Another popular legend involves a maiden named Yuan-Xiao, who supposedly worked in the imperial palace during the Han Dynasty. One cold winter’s day, the Emperor’s favourite adviser, Dongfang Shuo, was strolling through the imperial gardens when he came across Yuan-Xiao, who was weeping and preparing to throw herself into a well. Dongfang asked her why she wanted to end her life and Yuan-Xiao told him that she hadn’t seen her family since she had started working in the palace. If she couldn’t show her filial piety in this life, she would rather die. Dongfang was a kind man and said that, if she promised not to kill herself, he would find a way to reunite her with her family.

Dongfang then left the palace and disguised himself as a fortune-teller. People crowded round to ask for their fortune, but everyone was given the same prediction: an emissary of the God of Fire, dressed in red, would descend from heaven on the 13th lunar day and a catastrophic fire would burn down the city on the 15th. Rumour of this disaster spread quickly and the civilians decided that they would beg the emissary for mercy. On the 13th day, Yuan-Xiao pretended to be the emissary and, when the citizens pled with her, she demanded that they pass a decree from the God of Fire on to the Emperor.

The Emperor read the decree and, to his dismay, it stated that the city would be burned down on the 15th day. He immediately consulted Dongfang, who said that the God of Fire loved eating a sweet type of dumpling known as tangyuan, so the Emperor should command every household in the city to cook it. In order to deceive the god, every family should hang red lanterns outside of their homes and set off firecrackers so that the city would look like it was already ablaze. Finally, all of the civilians should be free to wander the streets and appreciate the decorations on the night of the 15th.

On that night, Yuan-Xiao’s parents were allowed into the palace to admire the lanterns and were reunited with their daughter. The celebration was so enjoyable that the Emperor decreed it should be practised every year and, since Yuan-Xiao cooked the best tangyuan, he named it the Yuanxiao Festival in her honour. So, the origins of the Lantern Festival may be diverse, but one thing is clear: deities love setting cities on fire and they are all easily fooled!

On that night, Yuan-Xiao’s parents were allowed into the palace to admire the lanterns and were reunited with their daughter. The celebration was so enjoyable that the Emperor decreed it should be practised every year and, since Yuan-Xiao cooked the best tangyuan, he named it the Yuanxiao Festival in her honour. So, the origins of the Lantern Festival may be diverse, but one thing is clear: deities love setting cities on fire and they are all easily fooled!

Nowadays it is generally separated into four sub-styles: Xiangfu, which originated from Kaifeng; Yudong, which arose in the Shangqiu region of eastern Henan; Yuxi, which became popular in the area surrounding the city of Luoyang; and Shahe, which came from Shahe County. Of these, the Yudong and Yuxi sub-styles are the most prevalent, and are known for their comedies and tragedies respectively.

Nowadays it is generally separated into four sub-styles: Xiangfu, which originated from Kaifeng; Yudong, which arose in the Shangqiu region of eastern Henan; Yuxi, which became popular in the area surrounding the city of Luoyang; and Shahe, which came from Shahe County. Of these, the Yudong and Yuxi sub-styles are the most prevalent, and are known for their comedies and tragedies respectively.

Yet some of these lanterns aren’t just for decoration! Throughout China, large groups of them will be strung up together in public parks and have small strips of paper pasted inside of them. Each piece of paper is inscribed with a riddle and locals will gather under the lanterns in order to solve them. If you think you’ve cracked one, you must take the piece of paper, find the person who wrote the riddle, and tell them your answer. Correct answers earn you a small prize, while incorrect ones mean that, like the lanterns, you’ll be hung out to dry!

Yet some of these lanterns aren’t just for decoration! Throughout China, large groups of them will be strung up together in public parks and have small strips of paper pasted inside of them. Each piece of paper is inscribed with a riddle and locals will gather under the lanterns in order to solve them. If you think you’ve cracked one, you must take the piece of paper, find the person who wrote the riddle, and tell them your answer. Correct answers earn you a small prize, while incorrect ones mean that, like the lanterns, you’ll be hung out to dry!

Another popular legend involves a maiden named Yuan-Xiao, who supposedly worked in the imperial palace during the Han Dynasty. One cold winter’s day, the Emperor’s favourite adviser, Dongfang Shuo, was strolling through the imperial gardens when he came across Yuan-Xiao, who was weeping and preparing to throw herself into a well. Dongfang asked her why she wanted to end her life and Yuan-Xiao told him that she hadn’t seen her family since she had started working in the palace. If she couldn’t show her filial piety in this life, she would rather die. Dongfang was a kind man and said that, if she promised not to kill herself, he would find a way to reunite her with her family.

Another popular legend involves a maiden named Yuan-Xiao, who supposedly worked in the imperial palace during the Han Dynasty. One cold winter’s day, the Emperor’s favourite adviser, Dongfang Shuo, was strolling through the imperial gardens when he came across Yuan-Xiao, who was weeping and preparing to throw herself into a well. Dongfang asked her why she wanted to end her life and Yuan-Xiao told him that she hadn’t seen her family since she had started working in the palace. If she couldn’t show her filial piety in this life, she would rather die. Dongfang was a kind man and said that, if she promised not to kill herself, he would find a way to reunite her with her family. On that night, Yuan-Xiao’s parents were allowed into the palace to admire the lanterns and were reunited with their daughter. The celebration was so enjoyable that the Emperor decreed it should be practised every year and, since Yuan-Xiao cooked the best tangyuan, he named it the Yuanxiao Festival in her honour. So, the origins of the Lantern Festival may be diverse, but one thing is clear: deities love setting cities on fire and they are all easily fooled!

On that night, Yuan-Xiao’s parents were allowed into the palace to admire the lanterns and were reunited with their daughter. The celebration was so enjoyable that the Emperor decreed it should be practised every year and, since Yuan-Xiao cooked the best tangyuan, he named it the Yuanxiao Festival in her honour. So, the origins of the Lantern Festival may be diverse, but one thing is clear: deities love setting cities on fire and they are all easily fooled!

The Dai calendar begins with a New Year celebration known as the Water Splashing Festival, which takes place sometime in April and is their first Buddhist festival of the year. It is sometimes called “Shanghan” or “Jingbimai” in the Dai language, meaning “New Year”, but is more often referred to as “Hounan” or “Water Splashing Festival”. The jovial nature and lively atmosphere of this festival has earned it great fame throughout China. That and it provides anyone with the opportunity to douse their friends in water!

The Dai calendar begins with a New Year celebration known as the Water Splashing Festival, which takes place sometime in April and is their first Buddhist festival of the year. It is sometimes called “Shanghan” or “Jingbimai” in the Dai language, meaning “New Year”, but is more often referred to as “Hounan” or “Water Splashing Festival”. The jovial nature and lively atmosphere of this festival has earned it great fame throughout China. That and it provides anyone with the opportunity to douse their friends in water!

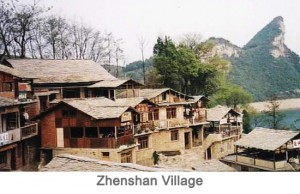

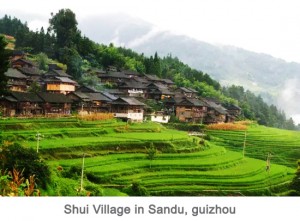

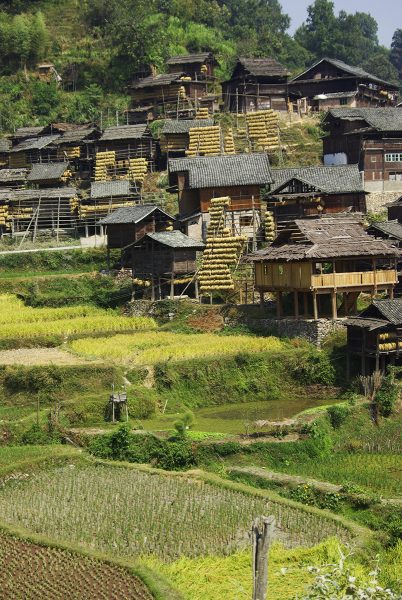

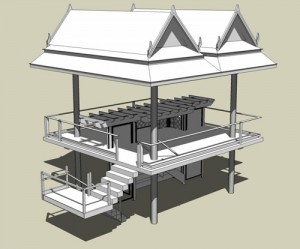

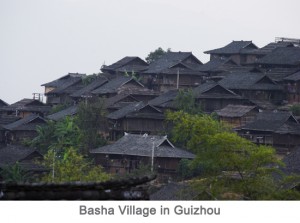

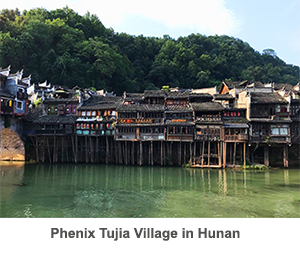

In contrast to the Miao people, the Tujia people prefer to live near mountains but close to or sometimes even over rivers or streams. Thus you’ll find that many Tujia diaojiaolou are either placed directly on the waterfront or hang over the water. The Tujia believe that these stilted houses embody the coexistence of God and man, so the designs of their diaojiaolou often reflect this. Tujia diaojiaolou are hard to come by, since the Tujia people are slowly abandoning their old settlements and assimilating into modern Chinese culture. The Tujia Folk Customs Park in Zhangjiajie, Hunan, is a large scale replica of a traditional Tujia village and features Tujia style Diaojiaolou. However, if you want a more authentic experience, we recommend visiting the Tujia village of Shuitianba in the Enshi Tujia and Miao Autonomous Prefecture of Hubei Province.

In contrast to the Miao people, the Tujia people prefer to live near mountains but close to or sometimes even over rivers or streams. Thus you’ll find that many Tujia diaojiaolou are either placed directly on the waterfront or hang over the water. The Tujia believe that these stilted houses embody the coexistence of God and man, so the designs of their diaojiaolou often reflect this. Tujia diaojiaolou are hard to come by, since the Tujia people are slowly abandoning their old settlements and assimilating into modern Chinese culture. The Tujia Folk Customs Park in Zhangjiajie, Hunan, is a large scale replica of a traditional Tujia village and features Tujia style Diaojiaolou. However, if you want a more authentic experience, we recommend visiting the Tujia village of Shuitianba in the Enshi Tujia and Miao Autonomous Prefecture of Hubei Province.