The custom of eating dim sum actually extends back to a much older tradition known as yum cha (饮茶) or “drinking tea”. Yum cha has been popular in Cantonese-speaking regions such as Guangdong province, Hong Kong, and Macau for decades, and is somewhat similar to the English custom of afternoon tea. The term refers to a type of meal that is usually eaten from early morning until mid-afternoon, where patrons drink Chinese tea and eat small dishes of food. It has its roots in the ancient Silk Road, when travellers would stop to rest at teahouses and order small snacks to give them a boost of energy.

While dim sum is the name used to describe the small dishes, the entire meal is generally known as yum cha. Since the meal is often eaten early in the day, most dim sum dishes are steamed or stir-fried rather than deep-fried to keep them tasting light and fresh. It is customary to offer a wide range of dishes, including savoury snacks like dumplings and sweet treats such as egg tarts. Each dish is usually quite small, with normally three to four bite-sized portions per plate. Dishes are shared among all of the diners at the table, allowing everyone to try a wide variety of food. That being said, after you’ve tasted a few delicious dim sum dishes, you may find you don’t want to share!

Traditional dim sum restaurants have a truly unique way of serving their miniature meals. Several dishes of dim sum are fully cooked and then placed on heated carts, which are wheeled around the restaurant. Diners are free to select what dishes they please without having to order from a menu, and a card at their table is stamped to indicate what they’ve taken. In this instance, dishes aren’t individually priced, but are instead priced according to size. They are generally classified as small, medium, large, extra-large, and special, with the “special” category referring to expensive dishes containing rare ingredients. Nowadays many restaurants only serve dim sum via the cart method during peak times, and revert to an à la carte menu during quieter periods so as to minimize food wastage.

Several types of tea are served alongside the dim sum, including chrysanthemum tea, green tea, oolong tea, pu’er tea, and a variety of scented teas. However, much like afternoon tea in England, the tea usually takes a backseat to the main event: the food! From bamboo steamers weighed down with plump dumplings to plates piled high with thickly sauced chickens’ feet, dim sum is a time to indulge in all the weird and wonderful treasures that Cantonese cuisine has to offer. We’ve listed just a handful of the standard dim sum dishes that you’re likely to come across, so prepare to get your taste-buds tingling!

Changfen (肠粉)

Commonly known in English as a rice noodle roll, Changfen is made from a wide, thin strip of rice noodle known as hor fun in Cantonese or Shahe fen in Mandarin Chinese. It is so-named because it is said to have originated from the district of Shahe in Guangzhou. The rice noodle sheets are made from a simple mixture of rice flour, glutinous rice flour, and water, which is spread thinly over a flat pan with holes and steamed until the sheet is cooked but still maintains its elasticity and sheen.

Commonly known in English as a rice noodle roll, Changfen is made from a wide, thin strip of rice noodle known as hor fun in Cantonese or Shahe fen in Mandarin Chinese. It is so-named because it is said to have originated from the district of Shahe in Guangzhou. The rice noodle sheets are made from a simple mixture of rice flour, glutinous rice flour, and water, which is spread thinly over a flat pan with holes and steamed until the sheet is cooked but still maintains its elasticity and sheen.

It is then folded approximately three times and served with a warm, sweetened soy sauce poured over the top. While the plain variety contains no filling, more popular types are filled with shrimp, pork, beef, vegetables, and a number of other ingredients. In this instance, most chefs will place the filling onto the noodle sheet before it has finished cooking. This means that, as the noodle continues to cook, it will set around the filling. A well-made Changfen should have two qualities: a good aroma, and a smooth or slippery texture. Just make sure it doesn’t slip right out of your chopsticks, or you’ll be bitterly disappointed!

The noodle should be a little transparent so as to slightly reveal the filling, and is typically scored three times at the top. The rolls are generally served in threes, because you can’t go wrong with the magic number! The most popular style of Changfen served during yum cha is known as Zhaliang (炸两). This involves tightly wrapping the rice noodle sheet around a piece of youtiao or fried dough. This fluffy treat is then served with a helping of sweetened soy sauce, hoisin sauce, or sesame paste. It is often eaten with soy milk or congee (Chinese rice porridge) as part of a hearty dim sum breakfast.

Dumplings (饺子)

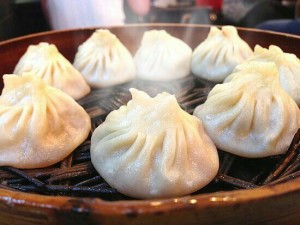

Whether it’s breakfast, lunch, or dinner, there’s never a bad time to gorge on a few dumplings! These plump parcels have been a staple in teahouses for centuries, and naturally made up part of the original platter on offer at the first dim sum restaurants. However, the dumplings you’ll find on the average dim sum plate will be very different to the Beijing dumplings that you might be used to. While Beijing dumplings are undoubtedly delicious, the sheer variety of dumplings available during yum cha might just make your head spin!

Whether it’s breakfast, lunch, or dinner, there’s never a bad time to gorge on a few dumplings! These plump parcels have been a staple in teahouses for centuries, and naturally made up part of the original platter on offer at the first dim sum restaurants. However, the dumplings you’ll find on the average dim sum plate will be very different to the Beijing dumplings that you might be used to. While Beijing dumplings are undoubtedly delicious, the sheer variety of dumplings available during yum cha might just make your head spin!

Popular types of dumpling in Cantonese cuisine include Har Gow (虾饺) and Fun Guo (潮州粉果), to name but a few. Har Gow are colloquially referred to as “shrimp’s bonnets” because of their characteristic ingredient and pleated shape. Traditionally, the perfect Har Gow should have at least seven but preferably ten or more pleats imprinted on its wrapper. The skin must be thin and translucent, but sturdy enough not to break when picked up with chopsticks.

On top of all this, the dumplings must not stick to each other, the shrimp must be thoroughly cooked but not rubbery, and each dumpling should contain a generous portion of meat but not so much that it cannot be eaten in one bite. A throne fit for a king may be hard to find, but making a bonnet fit for a shrimp is an arduous task indeed! The delicate nature of the dumplings means they require great skill to prepare, and are sometimes used as a test for aspiring dim sum chefs.

Fun Guo is a variety of steamed dumpling that originates from the Chaoshan region of Guangdong province. Much like Har Gow, the dumpling skins are made from glutinous rice flour, which endows each dumpling with their characteristically transparent skin. However, unlike Har Gow, the skins are a little thicker, resulting in a heartier flavour. They are typically filled with an aromatic mixture of minced pork, dried shrimp, chopped peanuts, chopped spring onions, and mushrooms. While Har Gow and Fun Guo are two staple types of dumpling in the dim sum canon, there are so many different varieties to choose from that you’re sure to be in dumpling heaven!

Baozi (包子)

What could be better than a dumpling? A giant dumpling, of course! Baozi or “Steamed Buns” are widely regarded as the dumpling’s larger, stockier cousin. These velvety soft buns can either be steamed or baked, and come in all shapes and sizes, from savoury to sweet and from meat-filled to vegetarian. When it comes to Cantonese dim sum, the most popular variety of baozi is known as the Char Siu Bao (叉烧包) or “Barbecued Pork Bun”. Steamed Char Siu Bao are white and fluffy in texture, while baked ones are coated with a light sugar glaze that gives them a temptingly golden brown crust. The dough used in this type of baozi is also unusual in that yeast and baking powder are added, which gives it the texture of slightly dense bread.

What could be better than a dumpling? A giant dumpling, of course! Baozi or “Steamed Buns” are widely regarded as the dumpling’s larger, stockier cousin. These velvety soft buns can either be steamed or baked, and come in all shapes and sizes, from savoury to sweet and from meat-filled to vegetarian. When it comes to Cantonese dim sum, the most popular variety of baozi is known as the Char Siu Bao (叉烧包) or “Barbecued Pork Bun”. Steamed Char Siu Bao are white and fluffy in texture, while baked ones are coated with a light sugar glaze that gives them a temptingly golden brown crust. The dough used in this type of baozi is also unusual in that yeast and baking powder are added, which gives it the texture of slightly dense bread.

In Cantonese cuisine, Char Siu is a type of siu mei or specialty barbecued meat. The cooking process involves slathering a fatty slice of pork in an aromatic mixture of honey, Chinese five-spice, red fermented bean curd, dark soy sauce, hoisin sauce, and Shaoxing rice wine before roasting it over a fire or in a rotisserie oven. The result is tender strips of pork that are beautifully marbled, mouth-wateringly moist, and dark red in hue. The pork is diced and added to a syrupy mixture of oyster sauce, hoisin sauce, roasted sesame oil, rice vinegar, soy sauce, sugar, and rice wine, which is then stuffed into the baozi. As the baozi is cooked, the meaty juices and thick sauce soak into the surrounding dough and impart a simply irresistible flavour.

Phoenix Claws (凤爪)

Don’t let the name fool you; Chinese biologists haven’t stumbled upon a mythical creature just yet! Phoenix Claws are the euphemistic and rather inventive way of referring to a classic dim sum dish made from chickens’ feet. In order to make the dish, chickens’ feet are first deep-fried and then steamed to make them puffy before being simmered in a sauce made from fermented black beans, black bean paste, and sugar.

Don’t let the name fool you; Chinese biologists haven’t stumbled upon a mythical creature just yet! Phoenix Claws are the euphemistic and rather inventive way of referring to a classic dim sum dish made from chickens’ feet. In order to make the dish, chickens’ feet are first deep-fried and then steamed to make them puffy before being simmered in a sauce made from fermented black beans, black bean paste, and sugar.

Some restaurants also serve a variation known as White Cloud Phoenix Claws (白云凤爪), where the chickens’ feet are simply steamed and served with a vinegar dipping sauce. While they may not look particularly appetising, the meat has a light and springy texture that perfectly complements the thick sweetness of the sauce. No dim sum dinner would be complete without this staple dish, so have a try and don’t be chicken!

Tofu Pudding (豆腐花)

Tofu Pudding is an archetypal example of the many wonderful desserts on offer during yum cha. The dish itself is as simple as it is delicious. Soft, silken tofu is spooned into a bowl and served with a clear sweet ginger or jasmine flavoured syrup, although in some restaurants it’s mixed with black bean paste or coconut milk instead. The result is a silky smooth dessert that tastes both delightfully sugary and refreshingly clean. It’s the ideal palate cleanser after a long meal of dumplings, steamed buns, and chickens’ feet!

Tofu Pudding is an archetypal example of the many wonderful desserts on offer during yum cha. The dish itself is as simple as it is delicious. Soft, silken tofu is spooned into a bowl and served with a clear sweet ginger or jasmine flavoured syrup, although in some restaurants it’s mixed with black bean paste or coconut milk instead. The result is a silky smooth dessert that tastes both delightfully sugary and refreshingly clean. It’s the ideal palate cleanser after a long meal of dumplings, steamed buns, and chickens’ feet!

Claypot rice ranks as one of the most iconic dishes in southern China and is particularly popular in Hong Kong, although it has long since spread to countries outside of China such as Singapore and Malaysia.

Claypot rice ranks as one of the most iconic dishes in southern China and is particularly popular in Hong Kong, although it has long since spread to countries outside of China such as Singapore and Malaysia.