The Guzang Festival has been shrouded in mystery for hundreds of years. It is a traditional festival of the Miao people but unlike other festivals in China, which are usually annual, the Guzang Festival only takes place once every twelve years. Preparations for this unusual festival begin two years before the festivities are due to start and the festival itself can last upwards of 15 days! The name Guzang derives from the two words “gu” and “zang”, which mean “drum” and “to bury” respectively. Thus “guzang” means “to bury the drum” as drums are particularly significant to this festival.

It is sometimes referred to as the Gushe Festival, as it was once a way of bringing together communities of kindred clans known as gushe. Every twelve years a different Miao village will host the festival, although a smaller festival is held every year that lasts only four days. Each year this smaller festival will have a different ritual theme and is sometimes referred to as the “Small Guzang Festival”. Ancient Miao songs indicate that the Guzang Festival was celebrated by early Miao clans during the Xia Dynasty (c. 2100-1600 B.C.), which would make this festival thousands of years old. The festival is particularly important to the Miao because it focuses on commemorating their ancestors, with particularly reference to their shared ancestors and origin story.

Origins of the Guzang Festival

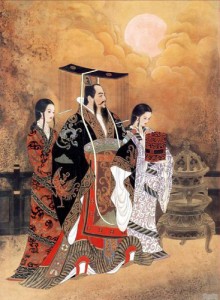

According to Miao legend, the origin of man began with a maple tree called the White Maple. After being struck down, this mystical tree went through a transformation. Its roots turned into fish, its trunk turned into a copper drum, its branches became a bird, and its core, or spiritual essence, manifested as a butterfly. This butterfly fell in love with and became pregnant by the foams of the waves.

She laid 12 eggs, which were hatched by the legendary bird Ziyu that had been born out of the White Maple. The eggs took 12 days and 12 nights to hatch. Out of these eggs were born the thunder god, the dragon, the ox, the tiger, the elephant, the snake, the centipede, a human boy, and his sister. Thereafter the butterfly was known as Mother Butterfly or Butterfly Mother. The boy, Jiangyang, and his sister are considered to be the first human beings on earth, so in Miao folklore Mother Butterfly is the equivalent of God in Christianity. She features prominently in Miao craftwork. The celebrations of the Guzang Festival are all based around some facet of this origin story.

Burying the Drum

Two different kinds of drum will be used during the festival: the double drum and the single drum. The double drum is made up of two single drums and is massive, averaging 170 centimetres in length and 30 centimetres in diameter. Before the festival, the double drums are usually kept in the house of a couple who is married but childless. The Miao believe that the presence of the double drum will help the couple conceive a child.

The single drum is substantially smaller than the double drum and a new one will be made for each festival. When the festival ends, this single drum will be placed in a cave, where it will be left to decay. This “burying” of the drum is where the festival derives its name. In July, before the next Guzang Festival, the hosting village will retrieve this old single drum as part of a ceremony known as Xinggu or “Awakening the Drum”. This takes place a year before the festivities begin. The hosting village will then make the new single drum.

The drums are crafted using maple wood, with cowhide covering both ends of each drum. Since the maple tree is revered by the Miao people as the origin of life, the Miao believe that the souls of their ancestors live inside these huge drums. They beat the drums loudly under maple trees in order to wake up their ancestors, who they believe will take part in the festival.

Festivities

Two years before the festival is supposed to take place, a leader will be chosen to begin the ceremonies and an organising committee will be formed. Usually the leader is an elderly married man from the community. During the festivities, this leader will wear a violet shirt and will sometimes have dried fish attached to his headdress. These fish symbolise the Miao’s belief that their ancestors used to live along the Yangtze River and sustained themselves by fishing.

As aforementioned, in July of the first year there is the “Awakening of the Drum” ceremony. A team is formed, made up of a priest, leaders from every village, and representatives from each clan. Together, they will go to the Drum Temple on the mountain to retrieve the old single drum. A mallard is sacrificed and its blood is sprinkled around the holy drum. The priest will then chant using special language in order to “wake up the drum”.

In October of the second year, there is a “Welcoming the Drum” ceremony. The same team from the first year assemble and welcome the holy drum into the village. Villagers will play the lusheng and dance to celebrate the coming of the drum.

During April of the third year, the leader is responsible for choosing the sacred bulls that will be sacrificed during the festivities. Once these bulls have been selected, they are fed well and must not be used for any kind of farm work. This ceremony is called Shenniu or “Inspecting the Cattle”. Not long after the cattle have been chosen, the leader will go to the previous hosting village to retrieve their single drum, as aforementioned.

After these two years have passed and the preparations are complete, the festival will begin. Throughout the fifteen days of the festival, bullfighting will take place between the sacred bulls and the Miao people are permitted to eat meat and bean curd but not vegetables of any kind. The first day of the festival is just a simple opening ceremony.

On the second day of the festival, the leader of the festival will travel into the mountains with a shaman in search of the soul of the dragon, which is a symbol of good luck. The shaman will carry a male duck around the mountain and guide the soul of the dragon into the duck in a ceremony known as Zhaolong or “Inviting the Dragon”. In the evening, a pig will be sacrificed and all of the participants will share the meat in a celebratory feast. Families will get together with friends and relatives from other villages to have their own feasts and these celebrations will go on late into the night. The sharing of the meat represents the union of the community, the harmonious relationships of the villagers and the preservation of ancient traditions. Good relations between families, distant relatives and members of other villages are integral to the survival of Miao culture.

On the third day, a large bronze drum will be hung from a green bough in the centre of the courtyard. This drum symbolises life and fertility. The shaman and the organising committee will form a circle around the drum and beat it, while being accompanied by men playing the lusheng. Young girls from surrounding villages will deck themselves out in traditional dress and dance around the drum. By the late afternoon, a huge circle of dancers will form. Newcomers will be welcomed to the festivities with liquor or “horn spirit” served from a bull’s horn. This dancing ceremony can last upwards of 4 to 6 hours.

Once the dancing has finished, the shaman will light incense, burn paper money and chant as part of an offering to the ancestors. Then there will be another feast in the village, and the organising committee will settle down to eat and discuss the festival. After the feast, an entertainment troupe from another village will be invited to perform. They will dance and sing Miao folk songs while the young people watch. On the afternoon of the fourth day, the drum will sound again, signifying the start of another dancing ceremony. In the evening, the shaman will end this dancing ceremony by making more offerings.

On the fifth day of the festival, the sacrificial bulls will be adorned with decorations and paraded around the village, with locals setting off firecrackers in their wake. On the dawn of the sixth day, the bulls will be sacrificed and their heads will be placed together facing east, which symbolises the belief that the Miao ancestors came from east China. A ceremony is held to release the souls of the bulls from purgatory and then villagers will sing ancient sacrificial songs. The meat from the bulls will be divided among the village households so they can all hold their own feasts.

Unfortunately, due to the bullfighting and the sacrifices, many bulls will die during this festival. Any bull that dies during the bull fights is commemorated as a hero and given a proper burial. His bravery will be recounted on his tombstone. In order to keep the mood light, the Miao will use euphemisms to describe any unsavoury event. For example, “kissing the big official” means butchering a pig, “give me the leaf” means “give me the butcher’s knife”, and “use the quilt to cover the official” stands for feeding straw into the stove fire in order to cook the pork.

The Guzang Festival reflects the Miao’s social values, with an emphasis on community, ancestor worship, hard work, piousness, peace and happiness. It is a truly magnificent spectacle and its rarity makes it even more enticing. Outsiders can participate in all of the festivities except for the Ancestor Worshipping Ceremony, so if you’re planning a trip to Guizhou and the Guzang Festival is approaching, we urge you to grasp this once in a lifetime opportunity.

Join a travel with us to experience the Guzang Festival with Miao People: Explore the culture of Ethnic minorities in Southeast Guizhou

The city of Turpan, also known as Turfan, lies about 180 kilometres (112 mi) southeast of the regional capital of Ürümqi, on the northern edge of the deep Turpan Depression. The Bogda Mountains, an eastern extension of the Tian Shan Mountains, rest to the north, while Qoltag Mountain rises to the south. Its unusual location means its climate is pretty unique, with long hot summers and cold brief winters.

The city of Turpan, also known as Turfan, lies about 180 kilometres (112 mi) southeast of the regional capital of Ürümqi, on the northern edge of the deep Turpan Depression. The Bogda Mountains, an eastern extension of the Tian Shan Mountains, rest to the north, while Qoltag Mountain rises to the south. Its unusual location means its climate is pretty unique, with long hot summers and cold brief winters. Nowadays the abundant sunshine and high temperatures in the city mean that it’s the ideal place for growing several types of fruit, particularly grapes and melons. The

Nowadays the abundant sunshine and high temperatures in the city mean that it’s the ideal place for growing several types of fruit, particularly grapes and melons. The  Yet perhaps Turpan’s greatest claim to fame is its prestigious heritage and the historical relics that surround it. The

Yet perhaps Turpan’s greatest claim to fame is its prestigious heritage and the historical relics that surround it. The