The works of Xuanzang (602 – 664) have provided invaluable insight into ancient civilizations and have been used by historians, geographers, philosophers, and archaeologists across the globe. Xuanzang was a monk, traveller, writer, historian, and translator, and somehow managed to succeed in every venture he put his mind to. His 16 year pilgrimage to India allowed him to collect hundreds of priceless artefacts, which he brought back to China to further the study of Buddhism. If it was not for his tireless efforts, many of the Buddhist texts and much of the information about ancient civilizations that we have today would have been lost.

Early Life

Xuanzang was born around about 602 A.D., in Goushi Town, Luozhou (near modern-day Luoyang, Henan), and was given the name Chen Hui. He was the youngest of four children and came from a long line of prestigious academics. His great-grandfather, Chen Qin, had served as the Prefect of Shangdang (modern-day Changzhi, Shanxi). His grandfather, Chen Kang, had been a professor at Taixue (the Imperial Academy). And his father, Chen Hui, was a conservative Confucian who served as the magistrate of Jiangling County during the Sui Dynasty.

Like his siblings, from an early age Xuanzang was educated by his father, who introduced him to the principles of Confucianism. He began observing Confucian rituals at the age of eight. Many of his family members were impressed with his early development and genius-level intellect.

Conversion to Buddhism

Although Xuanzang’s household was essentially Confucian, his older brother Chen Su was a Buddhist monk. Xuanzang expressed great interest in Buddhism and, when his father died in 611, he made the decision to live in Jingtu Monastery with his brother. He studied there for five years and, at the age of thirteen, he was ordained as a śrāmaṇera (novice monk).

In 618, both Xuanzang and his brother fled to Chang’an (modern-day Xi’an) to escape the unrest caused by the fall of the Sui Dynasty, and made their way to Chengdu, Sichuan, where they studied in Kong Hui Monastery. It was in this monastery that Xuanzang was ordained as a bhikṣu (full monk) at the age of twenty. In 622 he returned to Chang’an to study foreign languages and, in 626, he began learning Sanskrit. He chose to do this mainly because he was confused by the discrepancies in the Buddhist texts he had read and wanted to learn to translate the originals himself.

Pilgrimage

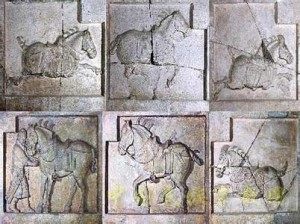

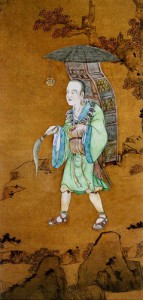

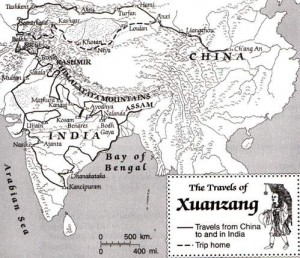

While studying in Chang’an, Xuanzang supposedly had a dream that indicated he should travel to India. It was this, coupled with his belief that the Buddhist texts available in China were insufficient, that convinced him to start his pilgrimage. However, at that time Emperor Taizong had prohibited foreign travel because of China’s war with the Göktürks[1], so in 629 Xuanzang slipped through the Yumen Pass under cover of darkness and made the dangerous journey across the Gobi Desert.

He eventually arrived in Liangzhou (modern-day Gansu province), which was the starting-point of the Silk Road trade route that connected China with Central Asia. He spent approximately a month preaching in Liangzhou before he was invited to Hami (modern-day Hami City, Xinjiang) by King Qu Wentai, who was a pious Buddhist of Chinese descent. However, it soon became apparent to Xuanzang that King Qu Wentai had ulterior motives. He planned to detain Xuanzang and make him the ecclesiastical head of his Court. Xuanzang went on a hunger strike until the King relented and allowed him to leave.

He eventually arrived in Liangzhou (modern-day Gansu province), which was the starting-point of the Silk Road trade route that connected China with Central Asia. He spent approximately a month preaching in Liangzhou before he was invited to Hami (modern-day Hami City, Xinjiang) by King Qu Wentai, who was a pious Buddhist of Chinese descent. However, it soon became apparent to Xuanzang that King Qu Wentai had ulterior motives. He planned to detain Xuanzang and make him the ecclesiastical head of his Court. Xuanzang went on a hunger strike until the King relented and allowed him to leave.

As a show of good faith, King Qu Wentai provided Xuanzang with introductions to all of the kings on his itinerary and also gave him sufficient supplies for his journey, without which Xuanzang’s pilgrimage may never have happened. By this point Xuanzang had achieved the reputation of an accredited scholar in China. In 630, Xuanzang embarked on a pilgrimage that would last just over 16 years. He visited many monasteries and religious sites on his journey, including the site where Buddha supposedly descended from heaven in Sankasya[2], his birthplace in Kapilavastu (southern Nepal), and the site of his death in Kusinagara (eastern India).

The most momentous stop on his journey was at the Nalanda Monastery, the most prestigious academic establishment in India at the time, which was located southwest of modern-day Bihar city. Nalanda consisted of some ten huge temples and, at that time, housed over ten thousand monks. According to legend, Silabhadra (529-645), the abbot of Nalanda, had considered committing suicide after years of suffering from illness when he was supposedly visited by deities in a dream. They commanded him to await the arrival of a Chinese monk who they claimed would spread the Mahayana[3] tradition across the world.

Silabhadra believed Xuanzang’s arrival fulfilled this prophecy and made Xuanzang his disciple. Under Silabhadra’s guidance, Xuanzang furthered his study of the Yogācāra branch of Buddhism. Yogācāra Buddhism is also called the Idealistic School. The central concept of this school is borrowed from a statement by the monk Vasubandhu, who said: “All this world is ideation only”. The basic concept of Yogācāra Buddhism is that the external world is merely a fabrication of our consciousness and does not actually exist, it is our internal ideas and past experiences that form what we perceive to be the outer world. The “real” world is simply our consciousness, so it is also sometimes referred to as the Consciousness Only branch of Buddhism.

Silabhadra believed Xuanzang’s arrival fulfilled this prophecy and made Xuanzang his disciple. Under Silabhadra’s guidance, Xuanzang furthered his study of the Yogācāra branch of Buddhism. Yogācāra Buddhism is also called the Idealistic School. The central concept of this school is borrowed from a statement by the monk Vasubandhu, who said: “All this world is ideation only”. The basic concept of Yogācāra Buddhism is that the external world is merely a fabrication of our consciousness and does not actually exist, it is our internal ideas and past experiences that form what we perceive to be the outer world. The “real” world is simply our consciousness, so it is also sometimes referred to as the Consciousness Only branch of Buddhism.

On leaving Nalanda, Xuanzang continued his pilgrimage until sometime between 643 and 644, when he decided to return to China. In 645 he finally arrived back in Chang’an and a great procession welcomed his return. He was immediately offered a ministerial position by Emperor Taizong but politely declined.

Religious Works

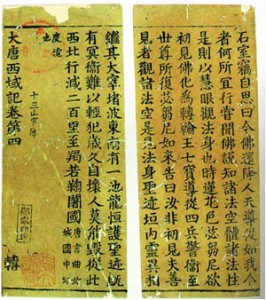

Xuanzang returned to China with seven statues of Buddha, over a hundred Buddhist relics and over 600 Buddhist texts. It was his aim to translate as many of these texts as he could so, with the support of the Emperor, he eventually masterminded the construction of the Giant Wild Goose Pagoda in Da Ci’en Temple, where he translated these works with the help of his fellow monks. In his lifetime, he was only able to translate about 75 of these texts into Chinese, which numbered about 1,300 sutras[4].

As a translator, Xuanzang wanted to present Buddhist texts to the Chinese in their entirety and so became well-known for his unabridged translations. When several of the original Indian scriptures were lost, his precise translations of them survived, meaning they have been preserved for posterity. An example of this is his translation of the Heart Sutra, which is the standard translation used by Buddhists today.

He also founded the Faxiang School of Buddhism based on his studies. During his lifetime, the school celebrated great popularity. Tragically, after his death, its popularity gradually declined but its teachings on consciousness, Karma, and other Buddhist principles were passed on to other, more successful schools, such as the Hossō School, which was one of the most influential Buddhist schools in Japan.

Literary Works

With the help of the monk Bianji, Xuanzang wrote one of the most famous literary works of the Tang Dynasty: Records of the Western Regions of the Great Tang Dynasty. It is sometimes referred to as Pilgrim to the West in the Tang Dynasty and Great Tang Records on the Western Regions. This novel is an invaluable academic resource because it records the geography, people, customs, history, religions, languages and cultures of about 140 countries that Xuanzang visited.

His travelogue inspired the famous Chinese epic Journey to the West by Wu Cheng’en. This novel was written in the 16th century during the Ming dynasty, around nine centuries after Xuanzang’s death. It is one of the Four Great Classical Novels of China. Outside of China, the abridged translation version Monkey by Arthur Waley is more well-known. In the novel, Xuanzhang is the reincarnation of the Golden Cicada, an original disciple of Buddha, and is protected on his pilgrimage by three supernatural beings, the most famous of which is the Monkey King.

His travelogue inspired the famous Chinese epic Journey to the West by Wu Cheng’en. This novel was written in the 16th century during the Ming dynasty, around nine centuries after Xuanzang’s death. It is one of the Four Great Classical Novels of China. Outside of China, the abridged translation version Monkey by Arthur Waley is more well-known. In the novel, Xuanzhang is the reincarnation of the Golden Cicada, an original disciple of Buddha, and is protected on his pilgrimage by three supernatural beings, the most famous of which is the Monkey King.

During the Tang Dynasty, Xuanzang was considered such a significant figure that, after his death, Emperor Gaozong cancelled all imperial audiences for three days in order to grieve. He was a pivotal figure in the development of Buddhist theory and his travelogues have given modern historians invaluable information about ethnic peoples and countries that have long been extinct. Modest and pious though he was, Xuanzang has arguably had a more powerful international impact than most emperors.

[1] Göktürks: A now extinct nomadic group of people, sometimes known as the Türks or the Ashina/Açina Turks, who were of Turkic descent and came from medieval Inner Asia.

[2] Sankasya: An ancient city in India that has since disappeared. It is sometimes known as Sankassa, Sankasia or Sankissa.

[3] Mahayana: One of the branches of Buddhism.

[4] Sutra: One of the sermons of the historical Buddha

The Wuyang Three Gorges are the most magnificent section of this scenic area. This is a 35-kilometre waterway that is made up of the Dragon King Gorge, the East Gorge and the West Gorge. Amongst these three gorges you’ll find powerful waterfalls crashing into the river, mysterious caves, the gentle gurgling of springs and the jagged figures of rocks emerging from the karst mountainsides. It is truly breath-taking to witness and we strongly recommend you take advantage of one of the local cruises in order to make the most of this scenic spot. It is said to be as spectacular as the Yangtze River Three Gorges and as mystical as the Li River in Guilin.

The Wuyang Three Gorges are the most magnificent section of this scenic area. This is a 35-kilometre waterway that is made up of the Dragon King Gorge, the East Gorge and the West Gorge. Amongst these three gorges you’ll find powerful waterfalls crashing into the river, mysterious caves, the gentle gurgling of springs and the jagged figures of rocks emerging from the karst mountainsides. It is truly breath-taking to witness and we strongly recommend you take advantage of one of the local cruises in order to make the most of this scenic spot. It is said to be as spectacular as the Yangtze River Three Gorges and as mystical as the Li River in Guilin.

Thanks to the Western expats now living in Yangshuo, the town boasts a variety of Western-style restaurants, cafés and bars that you won’t find in other Chinese towns. The food on offer in most of these restaurants is of a good standard and can provide a much needed rest from Chinese food if you’ve been travelling around the country for too long. Although most places close around 2am, Yangshuo boasts some of the most exciting nightlife in Guangxi. Many hostels will have their own bars and, coupled with the established bars and nightclubs in the town, this makes for a lively and unique atmosphere in the evenings. These hostel bars provide a wonderful opportunity to meet other travellers and backpackers on your journey.

Thanks to the Western expats now living in Yangshuo, the town boasts a variety of Western-style restaurants, cafés and bars that you won’t find in other Chinese towns. The food on offer in most of these restaurants is of a good standard and can provide a much needed rest from Chinese food if you’ve been travelling around the country for too long. Although most places close around 2am, Yangshuo boasts some of the most exciting nightlife in Guangxi. Many hostels will have their own bars and, coupled with the established bars and nightclubs in the town, this makes for a lively and unique atmosphere in the evenings. These hostel bars provide a wonderful opportunity to meet other travellers and backpackers on your journey. Although rice terraces wind their way around mountains throughout China, the Longji Rice Terraces are considered to be the most magnificent of them all. They are located in Longsheng County, about 100 kilometres (62 miles) outside of Guilin, and are sometimes referred to as the Longsheng Rice Terraces. The word “longji” means “dragon’s backbone” and these rice terraces earned their unusual name because the terraced fields climbing up the mountain look like dragons’ scales whilst the summit of the mountain range resembles a dragon’s backbone. This gives you an idea as to the sheer scale of these rice terraces.

Although rice terraces wind their way around mountains throughout China, the Longji Rice Terraces are considered to be the most magnificent of them all. They are located in Longsheng County, about 100 kilometres (62 miles) outside of Guilin, and are sometimes referred to as the Longsheng Rice Terraces. The word “longji” means “dragon’s backbone” and these rice terraces earned their unusual name because the terraced fields climbing up the mountain look like dragons’ scales whilst the summit of the mountain range resembles a dragon’s backbone. This gives you an idea as to the sheer scale of these rice terraces.

If you visit the city of Guilin, you will undoubtedly come across elephants. Whether they are in a business’ logo, a restaurant’s name, or on the front of a travel brochure, elephants have become a symbol of Guilin, and this is all thanks to Elephant Trunk Hill. Locals in Guilin say that if you have been to Elephant Trunk Hill then you have been to Guilin, which shows just how important this natural wonder is to the city and its people. Elephant Trunk Hill (Xiangbi Hill) is a Karst formation that has naturally formed on the western bank of the Li River just outside of Guilin city. It is so named because it looks like a thirsty elephant dipping its trunk into the river to drink. It rises over 55 metres over the waters of the Li River and measures 108 metres in length and 100 metres in width. In the past, it has been referred to by many names, such as “Li Hill”, “Yi Hill”, and “Chenshui Hill”, but it is now widely known as Elephant Trunk Hill.

If you visit the city of Guilin, you will undoubtedly come across elephants. Whether they are in a business’ logo, a restaurant’s name, or on the front of a travel brochure, elephants have become a symbol of Guilin, and this is all thanks to Elephant Trunk Hill. Locals in Guilin say that if you have been to Elephant Trunk Hill then you have been to Guilin, which shows just how important this natural wonder is to the city and its people. Elephant Trunk Hill (Xiangbi Hill) is a Karst formation that has naturally formed on the western bank of the Li River just outside of Guilin city. It is so named because it looks like a thirsty elephant dipping its trunk into the river to drink. It rises over 55 metres over the waters of the Li River and measures 108 metres in length and 100 metres in width. In the past, it has been referred to by many names, such as “Li Hill”, “Yi Hill”, and “Chenshui Hill”, but it is now widely known as Elephant Trunk Hill.