The Naxi ethnic minority have thrived in Yunnan for centuries and their complex yet fascinating Dongba culture is evidence of this. Dongba culture refers primarily to the written language, sculpture, artwork and architecture related to the Naxi religion known as Dongba. What makes Dongba culture so fascinating is that it encompasses the only known hieroglyphic writing system still in use; Dongba script. This script is made up of over 1,400 characters and symbols that are unique to the Naxi people. The Dongba Culture Museum is home to over 10,000 antiques, including more than 2,400 Dongba relics, making it the foremost institute for the preservation and research of Dongba culture. With its wonderful mixture of indoor, outdoor and live exhibits, the museum is sure to enliven as well as enlighten your day.

The Naxi people have lived in a number of towns scattered throughout Lijiang for centuries and thus played an instrumental role in commerce along the Tea-Horse Road. They prospered by selling their locally grown tea and handmade embroidered silk, which enabled them to build up a legacy and culture that many other ethnic groups of similar size weren’t able to achieve. This also meant that, as part of the major trade route, they came into contact with a myriad of other Asian cultures, from the Chinese Bai ethnic minority to traders from as far away as India. This intermingling of other, diverse cultures with their own has resulted in the captivating history, clothing, artwork, writing system and architecture that you can find in the museum today.

The museum is only about 300 metres from the back entrance to Black Dragon Pool in Lijiang Old Town, making it the perfect stop on your day out in Lijiang. It was founded in 1984 and built in the style of a traditional Naxi courtyard house. Its architecture is particularly stunning, with a charming arch and wide open spaces that allow it to host a myriad of exhibitions that even the largest indoor museums couldn’t dream of.

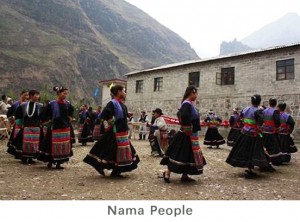

Within the indoor exhibits you’ll find many of the artefacts that have come to make the museum famous, such as Naxi paintings, Dongba holy books, religious sacrificial tools, and traditional festival clothing. The open air exhibits provide access to beautiful replicas of Naxi architecture throughout the ages, from ancient caves and wooden nest buildings to modern-day homes. Some of these dwellings look so cosy that you may be tempted to settle there but be forewarned, they have no central heating or internet access!

At set times during the day, local Naxi people descend upon the museum and re-enact Dongba religious rituals, such as the mystifying “sacrifice to heaven” ceremony, as part of their live exhibits. These performances are sure to take you back to a time when ancient elemental deities held sway over earth and shamans wrote their glyphic, unfathomable holy books, powdered herbal poultices for the sick and engaged in rituals to appease the gods. Just don’t interrupt a shaman at work, or you may end up as their next sacrifice!

Thus far, the Dongba Research Centre in Lijiang has managed to translate over 1,500 volumes of Dongba script. They have provided researchers with great insight into the history, culture and religion of the Naxi people, and this information has been passed on to visitors in the form of various introductions and exhibitions throughout the museum. With only about 30 Naxi people left in the world who can still write Dongba script, we recommend you head to the museum as soon as possible or risk missing out on this mysterious culture.