Deep within the Ganlan Basin, obscured by the verdant tropical jungles that loom over the banks of the Lancang River, the five small villages of the Dai Ethnic Garden have thrived for hundreds of years. They are just 28 kilometres from Jinghong, the capital city of Xishuangbanna Prefecture, and all of them are occupied by ethnically Dai people. The basin benefits from the hottest climate in Xishuangbanna and is able to sustain numerous tropical plant species, which is what earned the place the name “ethnic garden”. It is in fact more of a theme park, where visitors can learn about Dai culture and visit traditional Dai villages.

The villages are called Manjiang, Manchunman, Manting, Manzha, and Manga, and together they house approximately 300 families and 1,500 villagers. They consist primarily of traditional Dai buildings, which are square, two-storey houses that are built on stilts and made entirely from bamboo. The ground floor is used as a storehouse and stable for livestock while the upper floor is used as a living space. The upper floor is normally 2 metres off the ground and can be reached via a wooden ladder, which can make ascending the house with a hot cup of tea quite a challenge! Yet this is how the Dai people will undoubtedly welcome you, as they are known for their incredible hospitality. The Dai ethnic minority are traditionally Buddhist and so every village has its own Buddhist temple. It is important to note that you should take your shoes off before you enter any Dai home or temple, as a sign of respect.

Dai handicrafts are on sale throughout the villages and performances of Dai folk songs and dances, as well as other folk customs, occur regularly on the main stage. There is even a recreation of the Water Splashing Festival every day at 3pm, where visitors can join the Dai people near the fountain and throw water at each other. It’s one of the more delightful festivals celebrated by China’s ethnic minorities and nothing compares to the sheer joy of dousing your friends with buckets of water. If you want to extend your stay, there are plenty of guesthouses in each village that are sure to welcome you.

Manjiang

Manjiang

In the Dai language, the word “man” means “village”, while the word “jiang” means “strips of bamboo”. The Dai people commonly strap bamboo strips to heavy items in order to help carry them. According to local legend, long ago one of Buddha’s ancestors came to this village and commented on a stone, which he said had a particularly auspicious aura. He asked the locals if they could carry the stone to a small hill by the river, thus making the hill a holy place for people to visit. The stone was far too heavy to move simply by pushing it, but with the help of bamboo strips the locals were able to carry it up the hill. Buddha’s ancestor was elated and renamed the village Manjiang in honour of this good deed.

Manchunman

Manchunman

The name “manchunman” translates literally to mean “the village of gardens”. That being said, bizarrely Manchunman is not famous for its gardens but rather for the magnificent Buddhist temple at its centre. The Manchunman Buddhist Temple is over 1,400 years old, making it the oldest temple in Xishuangbanna, and stunning painted murals of Buddhist legends further enhance the value of this sacred place.

Manzha

You’ll be pleased to know that the word “manzha” translates to mean “cook’s village” so, if you’re looking for some tasty Dai dishes, this is the place to go! In ancient times, the tribal leader of the region would set aside a special village that was only to be inhabited by cooks. These chefs would train for years to prepare suitably delicious meals for the tribal leader. If you think having your own chef is indulgent, imagine having a whole village of them! Nowadays the villagers welcome visitors to try their local cuisine, which has been honed to perfection over hundreds of years. The 200-year-old Manzha Temple in the village is also worth noting, as it is one of the only Buddhist temples in existence that contains images and statues of monks but none of Buddha himself.

You’ll be pleased to know that the word “manzha” translates to mean “cook’s village” so, if you’re looking for some tasty Dai dishes, this is the place to go! In ancient times, the tribal leader of the region would set aside a special village that was only to be inhabited by cooks. These chefs would train for years to prepare suitably delicious meals for the tribal leader. If you think having your own chef is indulgent, imagine having a whole village of them! Nowadays the villagers welcome visitors to try their local cuisine, which has been honed to perfection over hundreds of years. The 200-year-old Manzha Temple in the village is also worth noting, as it is one of the only Buddhist temples in existence that contains images and statues of monks but none of Buddha himself.

Manting

Manting

Although the name “manting” means “court garden”, the village was once commonly known by its nickname, Peacock Village, thanks to the many tame peacocks that once populated Manting. Nowadays the village has become particularly famous for its White Pagodas and Buddhist Temple, which date all the way back to 669 AD. The statue of Buddha in the temple is said to be the largest in the Ganlan Basin.

Manga

In the Dai language, the name “manga” inexplicably means “going to the fair”; a name that seems completely unconnected to the village’s history. It is believed that Li Daorong, a man of the Han ethnic group, married a Dai woman and established the village. Thereafter, many Han people came from Guangdong and Guangxi to settle in Manga. Gradually members of the Han and Dai ethnic group mingled and so now many of the villagers are a mixture of these two ethnic groups.

In the Dai language, the name “manga” inexplicably means “going to the fair”; a name that seems completely unconnected to the village’s history. It is believed that Li Daorong, a man of the Han ethnic group, married a Dai woman and established the village. Thereafter, many Han people came from Guangdong and Guangxi to settle in Manga. Gradually members of the Han and Dai ethnic group mingled and so now many of the villagers are a mixture of these two ethnic groups.

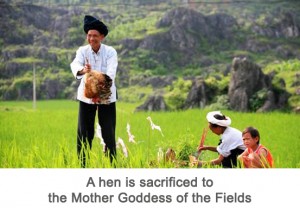

The Manga Temple, hidden in the forest behind the village, looks almost like a pavilion. Regardless of what time of day it is, the interior of the temple is always drenched in darkness and must be lit by candles or lighted lamps. Two door-gods flank the entrance and, deep within the temple, there lies an offering stand where locals can worship Li Daorong. On March 6th or July 7th every year, the Dai and Han people from Manga will bring a pig’s head, a cockerel, joss sticks, and paper money as sacrifices to Li Daorong.

The Peacock’s Tomb

The Peacock’s Tomb

According to local legend, in the 1960s a golden peacock inhabited the Ganlan Basin and, when it died, it brought great wealth to the local people. As a symbol of their appreciation, the people buried the peacock together with the treasured sword that once stood at the centre of the five villages. On the 14th day of July according to the Dai calendar, male villagers carry a pig’s head and wrapped rice to the tomb as offerings to the peacock. A large banquet will then be held and a memorial service for the peacock will take place.

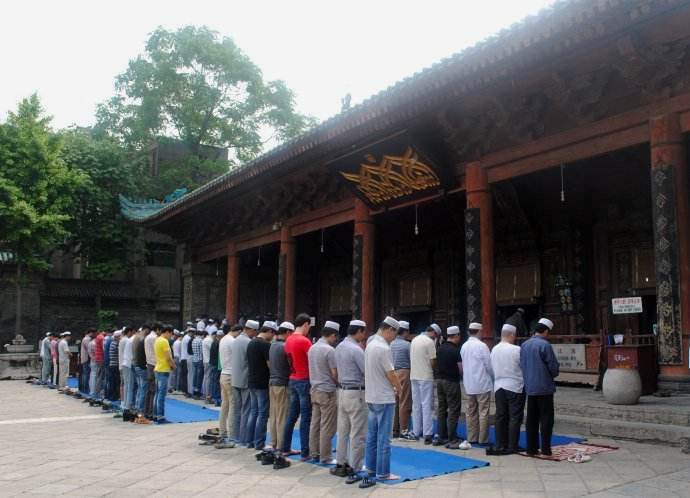

Thus the Hui people have a direct link not to China but to Central Asia. They have a varied ancestry that includes Arab, Persian, Mongol, Turkic and other Central Asian ancestors and their origins can be traced back in two ways. Some Hui people descended from Arab and Persian traders, who arrived in China via the Silk Road during the Tang Dynasty (618-907). Around the 7th century, some of them eventually settled in cities such as Guangzhou, Quanzhou, Hangzhou, Yangzhou and Chang’an (modern-day Xi’an) and were referred to as “fanke” or “guests from outlying regions”. Wherever they settled, they built mosques and public cemeteries. Over time they intermarried with Han people and converted their partners to Islam but largely assimilated with Chinese culture.

Thus the Hui people have a direct link not to China but to Central Asia. They have a varied ancestry that includes Arab, Persian, Mongol, Turkic and other Central Asian ancestors and their origins can be traced back in two ways. Some Hui people descended from Arab and Persian traders, who arrived in China via the Silk Road during the Tang Dynasty (618-907). Around the 7th century, some of them eventually settled in cities such as Guangzhou, Quanzhou, Hangzhou, Yangzhou and Chang’an (modern-day Xi’an) and were referred to as “fanke” or “guests from outlying regions”. Wherever they settled, they built mosques and public cemeteries. Over time they intermarried with Han people and converted their partners to Islam but largely assimilated with Chinese culture.