While wood, brick, concrete and even tile have been used to build houses for decades, the Dai ethnic minority are one of the few communities in China that have taken advantage of another novel and abundant resource. From the bases to the rafters, traditional Dai households are made almost entirely of bamboo! These two storey houses are normally square or rectangular in shape and their unique style dates back over 1,400 years. Large, load-bearing bamboo shafts are used to make the main framework of the house, whilst narrower ones are used to make the walls. In fact, the Dai have become so industrious with this versatile material that they even use bamboo twigs to bind together the bundles of dry grass used to thatch their roofs!

The upper floors of these houses are perched on thick stilts while the area under the stilts, or the ground floor, is either open or partially walled. This ground floor area is used to shelter livestock and store food, while the upper levels are used as a living space. Each household will have separate rooms for eating, working, and receiving guests, along with several bedrooms and a balcony used for drying laundry and storing the water tank. They are designed to be well-ventilated, as the Dai live in a very humid climate, and the living area is far off the ground to avoid flooding, poisonous snakes and insects such as mosquitoes. With a design this comprehensive, the only thing the Dai people have to worry about are hungry pandas!

According to local legend, the idea behind these houses came long ago, when a man named Zhu Geilang was travelling through Xishuangbanna. There he met a Dai youth named Yanken, who asked for his advice on how to build a better house. Zhu thought for a moment, then crouched down and pushed a few chopsticks into the earth. He took the hat from his head and placed it over the chopsticks, then turned to Yanken and said, “Just build it like this”. I dread to imagine what our houses would look like if we based them on our fashion choices!

The Dai people have an enduring reverence for water, so it should come as no surprise that every village has a water-well that is loved and respected by the community. However, these are no ordinary wells! They look like tiny towers, resplendent with metre-high archways, painted decorations, golden roofs, and even elaborate sculptures of animals. A fence surrounds the well itself, outside of which people must use a long-handled bamboo ladle to scoop water into their buckets. It is forbidden for children to play near the well, for women to wash clothes in the well, and for men to water their cattle at the well. Basically, play it safe and don’t do anything near the well!

The Dai people have an enduring reverence for water, so it should come as no surprise that every village has a water-well that is loved and respected by the community. However, these are no ordinary wells! They look like tiny towers, resplendent with metre-high archways, painted decorations, golden roofs, and even elaborate sculptures of animals. A fence surrounds the well itself, outside of which people must use a long-handled bamboo ladle to scoop water into their buckets. It is forbidden for children to play near the well, for women to wash clothes in the well, and for men to water their cattle at the well. Basically, play it safe and don’t do anything near the well!

The Dai are devout Buddhists and so each of their villages will have its own temple. These temples tend to conform to the traditional Buddhist style of architecture but have an ethnic flair and follow the Chinese tradition of being placed in isolated and auspicious locations on mountainsides or deep within forests. The average temple complex consists of a temple gate, a main hall, rooms for the resident monks to live in, and a special room for housing the drum.

Large temple complexes will have a number of pagodas that are used as repositories for Buddhist relics. The interior and exterior of the temple buildings are often painted with panoramic murals depicting scenes from both Dai folklore and Buddhist history. They typically feature images of Buddha, various princes and princesses, and animals such as white elephants, horses, and deer, all stunning in their multi-coloured glory.

The main hall is situated on the east-west axis and is the primary place of worship. Monks gather here to light incense, chant sutras, and conduct a number of other religious activities in reverence to Buddha. The hall is punctuated by a dividing wall, which is at the central point where the roof slopes down on either side. The side of the hall facing eastward is home to a large statue of Buddha, which is arguably the most vital feature of any Buddhist temple.

The Dai people traditionally depict Buddha in a sitting position with “snail-shaped”, “flame-shaped” or “lotus-flower-shaped” hair and an exposed right shoulder. In order to draw attention to both his intelligence and his fabulous hairdo, his head makes up one-third of the height of the statue, although smaller figures are usually more naturally proportioned. While the Han Chinese traditionally depict Buddha as plump and smiling, the Dai’s representation is usually much slimmer and has an elongated face transfixed in a subdued expression.

However, during the Ming Dynasty many of these records were changed to “prove” that their ancestors had originated from Nanjing and were related to the Han ethnic group. Many scholars believe that this was designed to curry favour with the ruling Han imperials and help Bai aristocrats gain official positions. The Bai people thus foster a belief in dual ancestral origins; on the one hand, they believe that their forefathers were high-ranking officials in the Nanzhao and Dali Kingdoms; on the other hand, they allege that their ancestors were Han people who came from Nanjing as part of the Ming army. In short, don’t ask a Bai person about their family history unless you have a lot of time on your hands!

However, during the Ming Dynasty many of these records were changed to “prove” that their ancestors had originated from Nanjing and were related to the Han ethnic group. Many scholars believe that this was designed to curry favour with the ruling Han imperials and help Bai aristocrats gain official positions. The Bai people thus foster a belief in dual ancestral origins; on the one hand, they believe that their forefathers were high-ranking officials in the Nanzhao and Dali Kingdoms; on the other hand, they allege that their ancestors were Han people who came from Nanjing as part of the Ming army. In short, don’t ask a Bai person about their family history unless you have a lot of time on your hands!

The cultivation of rice and maize are the chief means of subsistence for the Miao people. Rice, maize, millet and sweet potatoes are their staple foods, although in more northern areas they eat maize, buckwheat, potatoes and oats. Miao food typically employs sour and peppery flavours to enhance their dishes. Although the Miao diet is relatively simple, Miao dishes such as Fish in Sour Soup and snacks such as La Rou (a kind of cured, smoked bacon) are popular throughout Guizhou for their rich, flavoursome taste.

The cultivation of rice and maize are the chief means of subsistence for the Miao people. Rice, maize, millet and sweet potatoes are their staple foods, although in more northern areas they eat maize, buckwheat, potatoes and oats. Miao food typically employs sour and peppery flavours to enhance their dishes. Although the Miao diet is relatively simple, Miao dishes such as Fish in Sour Soup and snacks such as La Rou (a kind of cured, smoked bacon) are popular throughout Guizhou for their rich, flavoursome taste.

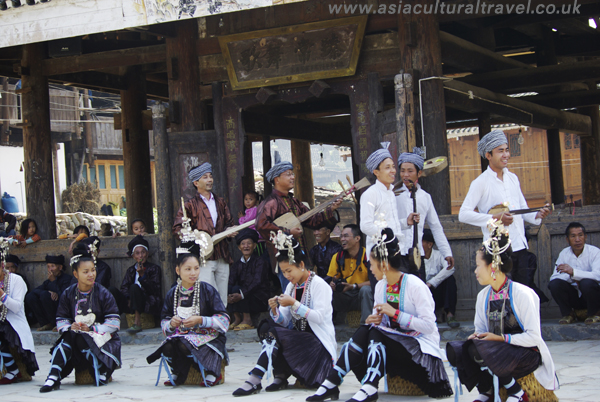

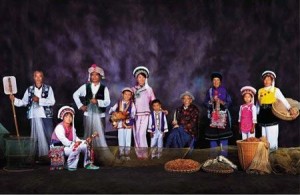

The daily clothing worn by Miao people will differ from place to place and many of the Miao subgroups are designated by the colour of their clothes, such as the Hmub Miao of southeast Guizhou who are often referred to as the Black Miao because of their characteristically indigo coloured clothing. In northwest Guizhou and northeast Yunnan, the Miao men will typically wear linen jackets that are colourfully embroidered and woollen blankets draped over their shoulders that are decorated in geometric patterns. In other areas, the men will wear short jackets that are buttoned down the front or to the left, long trousers with wide belts and long black scarves. In west Hunan and northeast Guizhou, the women wear jackets buttoned on the right and trousers that have delicately embroidered collars, sleeves and trouser legs. In other areas, the women wear high-collared short jackets and pleated skirts of varying length. These pleated skirts can have hundreds or even thousands of vertical pleats.

The daily clothing worn by Miao people will differ from place to place and many of the Miao subgroups are designated by the colour of their clothes, such as the Hmub Miao of southeast Guizhou who are often referred to as the Black Miao because of their characteristically indigo coloured clothing. In northwest Guizhou and northeast Yunnan, the Miao men will typically wear linen jackets that are colourfully embroidered and woollen blankets draped over their shoulders that are decorated in geometric patterns. In other areas, the men will wear short jackets that are buttoned down the front or to the left, long trousers with wide belts and long black scarves. In west Hunan and northeast Guizhou, the women wear jackets buttoned on the right and trousers that have delicately embroidered collars, sleeves and trouser legs. In other areas, the women wear high-collared short jackets and pleated skirts of varying length. These pleated skirts can have hundreds or even thousands of vertical pleats. On top of their beautifully embroidered clothes, Miao women are also famed for the glittering silver adornments that they wear during festival time. The Miao people regard silver as a symbol of wealth and so have a particular fondness for it. They also believe silver symbolises light and good health, so wearing silver will ward off evil spirits, stave off natural disasters and bring good fortune. When it comes to the ornamental silver worn by the Miao women, the heavier the better, so some festival outfits can weigh upwards of 20 to 30 jin (about 10 to 15 kg).

On top of their beautifully embroidered clothes, Miao women are also famed for the glittering silver adornments that they wear during festival time. The Miao people regard silver as a symbol of wealth and so have a particular fondness for it. They also believe silver symbolises light and good health, so wearing silver will ward off evil spirits, stave off natural disasters and bring good fortune. When it comes to the ornamental silver worn by the Miao women, the heavier the better, so some festival outfits can weigh upwards of 20 to 30 jin (about 10 to 15 kg).