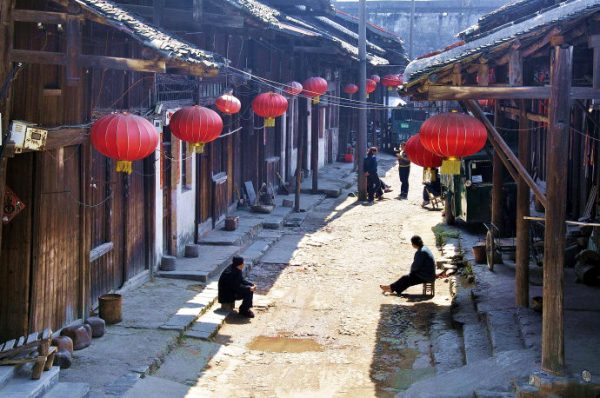

Daxu Ancient Town is like a small pearl nestled on the bank of the Li River. Although it is considered one of the Four Great Ancient Towns of Guangxi, it rarely receives visitors and has yet to be officially made into a tourist attraction. This means that, unlike other ancient towns, it is free to enter and there are hardly any crowds there to obstruct your unhindered joy of the fine architecture, flagstone streets, and locals plying their simple trade. Daxu Ancient Town is located on the east bank of the Li River, about 23 kilometres (14.3 miles) southeast of the city of Guilin. Its history dates back over 2,000 years, when Qin Shi Huang of the Qin Dynasty (221-206 B.C.) built the Lingqu Canal and connected the Xiang River from the Yangtze River system to the Li River.

Once these rivers were connected, Daxu begin to blossom as one of the leading trade and transportation hubs in the country. Daxu was one of the few ports along the river that connected Central China with South China, so it was a vital stopping point for traders transporting goods across the country. By the Northern Song Dynasty (960-1126), Daxu was one of the richest and most influential towns in Guangxi province. Its success peaked during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) and this was when many of its landmark buildings, such as the ancient main road and the Longevity Bridge, were built. However, by the late Qing Dynasty (1644-1912), the development of modern railways had rendered Daxu redundant as a trade hub and its prosperity rapidly declined. Thanks to the tireless efforts of the local people, unlike the ghost towns on the Silk Road, Daxu Ancient Town has continued to survive and thrive well into the 21st century.

The Old Street, which stretches 2.5 kilometres through the town, is the greatest remnant of the town’s glorious past. It is paved with blue flagstones that have been worn smooth by centuries of footsteps, cartwheels and horse hooves. The thirteen docks that were once used during Daxu’s booming era of trade still stand and five of them are so well-maintained that they are still in use today. As you traverse the Old Street, walking along the same path that so many before you have tread, and reach the fine docks with their simple, wooden platforms, you’ll undoubtedly be transported back to a humbler time, when merchants dressed in silk finery would load their boats with spices, embroidered cloths, and shimmering jewellery, and set sail down the river to the next trade port.

Many of the buildings in Daxu were built during the Ming and Qing dynasties and have sustained the intricate, architectural touches from that time. These wood and stone buildings are decorated with beautiful carvings and the Hanhuang Temple, Gaozu Temple and Longevity Temple are the finest examples of this architectural style. All of these temples were built during the Qing Dynasty, when the town was still prospering, and they exquisitely exhibit the artistry of the architecture at that time. With so many temples in one small place, it is no wonder that Daxu seems so tranquil.

However, the star attraction of Daxu is undoubtedly the Wanshou or Longevity Bridge. This stone arch dates all the way back to the Ming Dynasty and, though simplistic in its design, it provides a wonderful vantage point from which to admire the Li River. If you stand on Longevity Bridge and look out to the west bank, you’ll be greeted with scenes of lush greenery, winding waters, and water buffalo quietly grazing on the shores. Directly across from the bridge, you’ll be met with Millstone Hill and Snail Hill, two of the Karst formations whose names derive from their unusual shapes. Though the architecture of the Longevity Bridge may not be as magnificent as that of the Longevity Temple, the view from the bridge is unmatched.

However, the star attraction of Daxu is undoubtedly the Wanshou or Longevity Bridge. This stone arch dates all the way back to the Ming Dynasty and, though simplistic in its design, it provides a wonderful vantage point from which to admire the Li River. If you stand on Longevity Bridge and look out to the west bank, you’ll be greeted with scenes of lush greenery, winding waters, and water buffalo quietly grazing on the shores. Directly across from the bridge, you’ll be met with Millstone Hill and Snail Hill, two of the Karst formations whose names derive from their unusual shapes. Though the architecture of the Longevity Bridge may not be as magnificent as that of the Longevity Temple, the view from the bridge is unmatched.

In the 1990s, an element of mystery was added to Daxu Ancient Town when archaeologists unearthed what are now known as the Seven Star Tombs. These are seven tombs that were found arranged in the shape of the Big Dipper constellation. The size of each tomb is based on the brightness of the star it was meant to represent. It is the first recorded case of such a tomb site in China and the connection between the tombs and the Big Dipper constellation has yet to be elucidated. However, many ancient artefacts, such as pottery and bronze swords, have been excavated from the tombs. Thanks to carbon dating, these artefacts have shown that these tombs date all the way back to the period between the Warring States Period (c. 476-221 B.C.) and the Western Han Dynasty (207 B.C.-25 A.D.).

Aside from the historical importance of Daxu, this town is also a wonderful example of living history. Many of the villagers in Daxu all ply their own traditional handicrafts. The women of Daxu still brew their baijiu[1] using old barrels and a simple distillery, an archaic method for making baijiu that has all but disappeared in more urban parts of China. The locals still craft their bamboo baskets and straw sandals carefully by hand and the traditional Chinese medical clinics, of which there are about 20 in Daxu, still disseminate an aroma of medicinal herbs and traditional remedies throughout the town. Daxu is not simply an ancient town; it is a place of ancient tradition.

To truly immerse yourself in these ancient traditions, we recommend you wander through the streets during market time. This market has been a staple part of daily life in Daxu since the Ming Dynasty, although it has grown smaller over the years. Many villagers will each set up a stall, some selling handicrafts, such as paintings, ceramics or woven cloths, other selling Chinese medicines, and still others plying local delicacies such as quail’s eggs, dried fruit and homemade dumplings. The market is a spectacle of ancient Chinese culture that should not be missed. If you want to immerse yourself in the more rural life of Daxu, some of the local farmers will allow you to go fruit picking on their land. Picking strawberries near the Li River is a wonderful way to while away a few hours and harvest some delicious snacks in the process.

Daxu Ancient Town is relatively easy to get to. There are regular buses from Guilin Bus station that take about 40 minutes to reach the town.

[1] Baijiu: It literally means “white alcohol” or “white liquor” in Chinese. It is a strong, clear spirit that is usually distilled from sorghum, glutinous rice or wheat.

The Wuyang Three Gorges are the most magnificent section of this scenic area. This is a 35-kilometre waterway that is made up of the Dragon King Gorge, the East Gorge and the West Gorge. Amongst these three gorges you’ll find powerful waterfalls crashing into the river, mysterious caves, the gentle gurgling of springs and the jagged figures of rocks emerging from the karst mountainsides. It is truly breath-taking to witness and we strongly recommend you take advantage of one of the local cruises in order to make the most of this scenic spot. It is said to be as spectacular as the Yangtze River Three Gorges and as mystical as the Li River in Guilin.

The Wuyang Three Gorges are the most magnificent section of this scenic area. This is a 35-kilometre waterway that is made up of the Dragon King Gorge, the East Gorge and the West Gorge. Amongst these three gorges you’ll find powerful waterfalls crashing into the river, mysterious caves, the gentle gurgling of springs and the jagged figures of rocks emerging from the karst mountainsides. It is truly breath-taking to witness and we strongly recommend you take advantage of one of the local cruises in order to make the most of this scenic spot. It is said to be as spectacular as the Yangtze River Three Gorges and as mystical as the Li River in Guilin.

The cultivation of rice and maize are the chief means of subsistence for the Miao people. Rice, maize, millet and sweet potatoes are their staple foods, although in more northern areas they eat maize, buckwheat, potatoes and oats. Miao food typically employs sour and peppery flavours to enhance their dishes. Although the Miao diet is relatively simple, Miao dishes such as Fish in Sour Soup and snacks such as La Rou (a kind of cured, smoked bacon) are popular throughout Guizhou for their rich, flavoursome taste.

The cultivation of rice and maize are the chief means of subsistence for the Miao people. Rice, maize, millet and sweet potatoes are their staple foods, although in more northern areas they eat maize, buckwheat, potatoes and oats. Miao food typically employs sour and peppery flavours to enhance their dishes. Although the Miao diet is relatively simple, Miao dishes such as Fish in Sour Soup and snacks such as La Rou (a kind of cured, smoked bacon) are popular throughout Guizhou for their rich, flavoursome taste.

The daily clothing worn by Miao people will differ from place to place and many of the Miao subgroups are designated by the colour of their clothes, such as the Hmub Miao of southeast Guizhou who are often referred to as the Black Miao because of their characteristically indigo coloured clothing. In northwest Guizhou and northeast Yunnan, the Miao men will typically wear linen jackets that are colourfully embroidered and woollen blankets draped over their shoulders that are decorated in geometric patterns. In other areas, the men will wear short jackets that are buttoned down the front or to the left, long trousers with wide belts and long black scarves. In west Hunan and northeast Guizhou, the women wear jackets buttoned on the right and trousers that have delicately embroidered collars, sleeves and trouser legs. In other areas, the women wear high-collared short jackets and pleated skirts of varying length. These pleated skirts can have hundreds or even thousands of vertical pleats.

The daily clothing worn by Miao people will differ from place to place and many of the Miao subgroups are designated by the colour of their clothes, such as the Hmub Miao of southeast Guizhou who are often referred to as the Black Miao because of their characteristically indigo coloured clothing. In northwest Guizhou and northeast Yunnan, the Miao men will typically wear linen jackets that are colourfully embroidered and woollen blankets draped over their shoulders that are decorated in geometric patterns. In other areas, the men will wear short jackets that are buttoned down the front or to the left, long trousers with wide belts and long black scarves. In west Hunan and northeast Guizhou, the women wear jackets buttoned on the right and trousers that have delicately embroidered collars, sleeves and trouser legs. In other areas, the women wear high-collared short jackets and pleated skirts of varying length. These pleated skirts can have hundreds or even thousands of vertical pleats. On top of their beautifully embroidered clothes, Miao women are also famed for the glittering silver adornments that they wear during festival time. The Miao people regard silver as a symbol of wealth and so have a particular fondness for it. They also believe silver symbolises light and good health, so wearing silver will ward off evil spirits, stave off natural disasters and bring good fortune. When it comes to the ornamental silver worn by the Miao women, the heavier the better, so some festival outfits can weigh upwards of 20 to 30 jin (about 10 to 15 kg).

On top of their beautifully embroidered clothes, Miao women are also famed for the glittering silver adornments that they wear during festival time. The Miao people regard silver as a symbol of wealth and so have a particular fondness for it. They also believe silver symbolises light and good health, so wearing silver will ward off evil spirits, stave off natural disasters and bring good fortune. When it comes to the ornamental silver worn by the Miao women, the heavier the better, so some festival outfits can weigh upwards of 20 to 30 jin (about 10 to 15 kg).

Nowadays the temple is full of interesting historical sites and stunning gardens that are regularly enjoyed by tourists and locals alike. The temple site is separated into four parts: the North, South, East, and West Squares. In the North Square you’ll find a copper statue of an ancient book that tells the story of how the Tang Dynasty rose to power. There are two Buddhist beacons in this square, both 9 metres tall, which are designed after the famous Mogao Grottoes in Dunhuang. You’ll also find statues of famous figures from the Tang Dynasty, such as the poets Li Bai, Du Fu, Wang Wei, and Han Yu, the unparalleled calligrapher Huai Su, and the “King of Chinese Medicine” Sun Simiao, scattered throughout the square.

Nowadays the temple is full of interesting historical sites and stunning gardens that are regularly enjoyed by tourists and locals alike. The temple site is separated into four parts: the North, South, East, and West Squares. In the North Square you’ll find a copper statue of an ancient book that tells the story of how the Tang Dynasty rose to power. There are two Buddhist beacons in this square, both 9 metres tall, which are designed after the famous Mogao Grottoes in Dunhuang. You’ll also find statues of famous figures from the Tang Dynasty, such as the poets Li Bai, Du Fu, Wang Wei, and Han Yu, the unparalleled calligrapher Huai Su, and the “King of Chinese Medicine” Sun Simiao, scattered throughout the square.

After the death of the Emperor in 210 B.C., the Mausoleum was hermetically-sealed and remained unopened for nearly 2,000 years. It wasn’t until 1974, when some farmers were attempting to dig a water-well near Mount Li, that Pit one of the Terracotta Army was accidentally unearthed. Archaeologists flocked to the site and began excavating the area, eventually discovering three more pits of Terracotta Warriors in the process. The warriors were all found arranged as if to protect the tomb from the east, which is where all of the states that were conquered by the Qin Dynasty lay. To date, approximately 8,000 soldiers, 130 chariots with 520 horses and 150 cavalry horses have been uncovered from these pits.

After the death of the Emperor in 210 B.C., the Mausoleum was hermetically-sealed and remained unopened for nearly 2,000 years. It wasn’t until 1974, when some farmers were attempting to dig a water-well near Mount Li, that Pit one of the Terracotta Army was accidentally unearthed. Archaeologists flocked to the site and began excavating the area, eventually discovering three more pits of Terracotta Warriors in the process. The warriors were all found arranged as if to protect the tomb from the east, which is where all of the states that were conquered by the Qin Dynasty lay. To date, approximately 8,000 soldiers, 130 chariots with 520 horses and 150 cavalry horses have been uncovered from these pits. The Museum of Qin Terracotta Warriors and Horses and the Qin Shi Huang Mausoleum have now been incorporated into one tourist attraction known as Emperor Qin Shi Huang’s Mausoleum Site Park. There you’ll find regular free shuttle buses that will take you from the site of the Terracotta Army to Lishan Garden. Lishan Garden acts as the perfect complement to the Terracotta Army as it contains Qin Shi Huang’s burial mound, ritual sacrifice pits, the Museum of Terracotta Acrobatics, the Museum of Terracotta Civil Officials, the Museum of Stone Armour and the Museum of Bronze Chariots and Horses. The Museum of Bronze Chariots and Horses is a wonderful exhibition of all the figures found throughout the pits that are crafted from bronze rather than terracotta. They loom out of their glass cases, lifelike in their shimmering skin. The other museums are based around pits where terracotta figures are still being excavated and present the perfect opportunity to watch a live archaeological dig. The chance to watch the Terracotta figures being unearthed and thus the opportunity to watch history being made is one that we know you won’t want to pass up. The only area that is not open to the public and has not been excavated is the main tomb, where the Emperor’s remains rest. In spite of an on-going debate as to whether the tomb should be opened or not, it is universally thought that it will remain undisturbed as a mark of respect to the Emperor.

The Museum of Qin Terracotta Warriors and Horses and the Qin Shi Huang Mausoleum have now been incorporated into one tourist attraction known as Emperor Qin Shi Huang’s Mausoleum Site Park. There you’ll find regular free shuttle buses that will take you from the site of the Terracotta Army to Lishan Garden. Lishan Garden acts as the perfect complement to the Terracotta Army as it contains Qin Shi Huang’s burial mound, ritual sacrifice pits, the Museum of Terracotta Acrobatics, the Museum of Terracotta Civil Officials, the Museum of Stone Armour and the Museum of Bronze Chariots and Horses. The Museum of Bronze Chariots and Horses is a wonderful exhibition of all the figures found throughout the pits that are crafted from bronze rather than terracotta. They loom out of their glass cases, lifelike in their shimmering skin. The other museums are based around pits where terracotta figures are still being excavated and present the perfect opportunity to watch a live archaeological dig. The chance to watch the Terracotta figures being unearthed and thus the opportunity to watch history being made is one that we know you won’t want to pass up. The only area that is not open to the public and has not been excavated is the main tomb, where the Emperor’s remains rest. In spite of an on-going debate as to whether the tomb should be opened or not, it is universally thought that it will remain undisturbed as a mark of respect to the Emperor.