The Bai people celebrate a myriad of indigenous festivals, from the Folk Song Festival on Mount Shibao to the Rao San Ling Festival, but the three most important festivals are the Sanyue Festival, Torch Festival, and Benzhu Festivals.

The Sanyue Festival

The Sanyue or “March” Festival is the grandest in the Bai calendar and is held annually at the foot of Mount Cangshan near Dali from the 15th to the 20th day of the 3rd lunar month. Although it is called the March Festival, it actually falls sometime in April. Originally it began as a religious festival to pay homage to Guanyin, the Buddhist Goddess of Mercy. According to legend, Guanyin once rescued the residents of the Erhai region from certain death by defeating a band of man-eating Raksa demons. Thank goodness she got rid of all of them, or else Yunnan’s tourist trade would have definitely suffered!

The Sanyue or “March” Festival is the grandest in the Bai calendar and is held annually at the foot of Mount Cangshan near Dali from the 15th to the 20th day of the 3rd lunar month. Although it is called the March Festival, it actually falls sometime in April. Originally it began as a religious festival to pay homage to Guanyin, the Buddhist Goddess of Mercy. According to legend, Guanyin once rescued the residents of the Erhai region from certain death by defeating a band of man-eating Raksa demons. Thank goodness she got rid of all of them, or else Yunnan’s tourist trade would have definitely suffered!

From then on, the people held an annual Guanyin Market in her honour and this slowly became a fully-fledged festival. These occasions were particularly important in ancient China since they offered merchants from Tibet, Sichuan, Guangdong, and Hunan the chance to peddle their wares and buy goods that they rarely had access to. It is thought this type of market dates all the way back to the Tang Dynasty (618-907)! Over time the Sanyue Festival has evolved into a fair where sports competitions, dance performances, and the trading of goods have become the focal attraction. After all, we’re pretty sure the Goddess of Mercy wouldn’t mind people having a little fun!

The Torch Festival

The Torch Festival is celebrated by numerous ethnic minorities throughout southwest China, but is celebrated by the Bai people on the 25th day of the 6th lunar month, meaning it falls sometime in July. On the day of the festival, villagers light torches and carry them around the fields to drive away insects. They believe this will usher in a bumper harvest and bless the locals with good health and fortune. Doorways and village gates will be decorated with streamers bearing auspicious words that are also flanked by torches. The words must be particularly lucky, as miraculously these paper streamers never catch fire! In some villages, the locals will gather around large bonfires in nearby fields.

The Torch Festival is celebrated by numerous ethnic minorities throughout southwest China, but is celebrated by the Bai people on the 25th day of the 6th lunar month, meaning it falls sometime in July. On the day of the festival, villagers light torches and carry them around the fields to drive away insects. They believe this will usher in a bumper harvest and bless the locals with good health and fortune. Doorways and village gates will be decorated with streamers bearing auspicious words that are also flanked by torches. The words must be particularly lucky, as miraculously these paper streamers never catch fire! In some villages, the locals will gather around large bonfires in nearby fields.

The origin of the Torch Festival is recounted in a Bai folk song known as “The Burning of the Torches in the Hall”. This song recounts how Piluoge, the founder and king of the Nanzhao Kingdom (738-902), invited the leaders of the other five warring tribes to a sumptuous banquet in Songming Tower. When they arrived, he betrayed them and burned them all to death. Talk about a warm welcome! Many other ethnic groups in southwest China celebrate this festival to commemorate their ancient kings, who were murdered by Piluoge. However, nowadays the festival is barely connected to the original legend and has become a standardised way of worshipping for ample crops and prosperity in the coming year.

The Benzhu Festivals

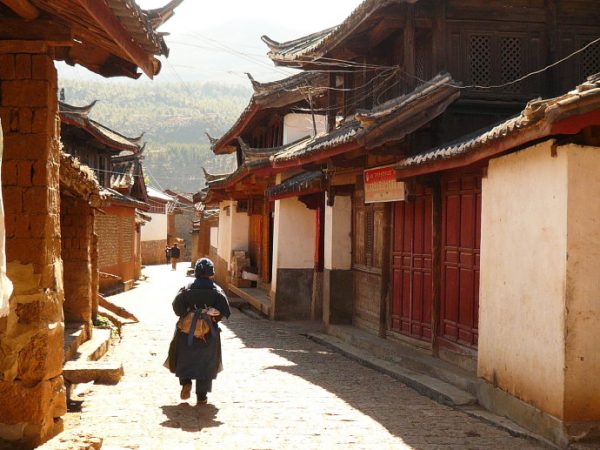

In the villages around Dali, the Benzhu Festival takes place twice every year but the largest and most magnificent one comes directly after Spring Festival. On the morning of the festival, all of the villagers will don their festive clothes and gather in the Benzhu Temple. The benzhu shrines are taken from the temple, placed on a colourfully decorated sedan chair, and paraded through the village. The shrines must pass through every street of the village with people burning incense and chanting scriptures in their wake. Finally they are deposited in a specified location, where they will remain for a number of days.

In the villages around Dali, the Benzhu Festival takes place twice every year but the largest and most magnificent one comes directly after Spring Festival. On the morning of the festival, all of the villagers will don their festive clothes and gather in the Benzhu Temple. The benzhu shrines are taken from the temple, placed on a colourfully decorated sedan chair, and paraded through the village. The shrines must pass through every street of the village with people burning incense and chanting scriptures in their wake. Finally they are deposited in a specified location, where they will remain for a number of days.

During the festival, the villagers must follow the gods and worship the shrines in their new location by burning incense and offering them food and money. In some villages, a temporary temple is built around the shrines just for the purposes of the festival! Throughout the festival, families will host feasts and invite their friends and relatives to join them. Some communities will even have a public feast, which takes place in a large open space in the village.

However, during the Ming Dynasty many of these records were changed to “prove” that their ancestors had originated from Nanjing and were related to the Han ethnic group. Many scholars believe that this was designed to curry favour with the ruling Han imperials and help Bai aristocrats gain official positions. The Bai people thus foster a belief in dual ancestral origins; on the one hand, they believe that their forefathers were high-ranking officials in the Nanzhao and Dali Kingdoms; on the other hand, they allege that their ancestors were Han people who came from Nanjing as part of the Ming army. In short, don’t ask a Bai person about their family history unless you have a lot of time on your hands!

However, during the Ming Dynasty many of these records were changed to “prove” that their ancestors had originated from Nanjing and were related to the Han ethnic group. Many scholars believe that this was designed to curry favour with the ruling Han imperials and help Bai aristocrats gain official positions. The Bai people thus foster a belief in dual ancestral origins; on the one hand, they believe that their forefathers were high-ranking officials in the Nanzhao and Dali Kingdoms; on the other hand, they allege that their ancestors were Han people who came from Nanjing as part of the Ming army. In short, don’t ask a Bai person about their family history unless you have a lot of time on your hands!