The Zhuang have a rich literary tradition, both written and unwritten. Folk stories often take the form of songs and are passed down orally. They can be myths, legends, historical poems or even simply chants. The Zhuang have a written language known as Sawndip or Old Zhuang Script, which they use to transcribe their literature and other important documents such as contracts. Most of these folk tales are written in verse and some of them are over a thousand years old!

One of these ancient legends has garnered much attention in recent years and is known as “Dahgyax Dahbengz” or “The Orphan Girl and the Rich Girl”. This is essentially an early version of the Cinderella story and has been found in old Zhuang opera scripts. Several written versions of the story date back to the 9th century, although it could be even older! Songs like these are often refined over a period of several years. For example, the “Song to Tell Others”, which is a philosophy on life, originated during the Sui Dynasty (581-618) but its final form wasn’t set until the late Ming Dynasty (1368-1644).

One of these ancient legends has garnered much attention in recent years and is known as “Dahgyax Dahbengz” or “The Orphan Girl and the Rich Girl”. This is essentially an early version of the Cinderella story and has been found in old Zhuang opera scripts. Several written versions of the story date back to the 9th century, although it could be even older! Songs like these are often refined over a period of several years. For example, the “Song to Tell Others”, which is a philosophy on life, originated during the Sui Dynasty (581-618) but its final form wasn’t set until the late Ming Dynasty (1368-1644).

Many of these songs have their roots in superstition, such as the “house raising” song which is sang after a new house is built. This song consists of two parts; the first describes the construction of a traditional stilt house; and the second is customarily believed to ward off evil spirits from the new home. Like many ethnic minorities, they are a deeply superstitious people and their customs reflect this. For example, in some Zhuang communities they love to eat dog meat, while in others there is a taboo on eating dog meat because, according to legend, the dog helped mankind in their time of need.

The legend states that long ago there were no grains and the people were forced to eat wild plants. The only grain seeds were in Heaven but it was forbidden to bring them to earth. One day, a trusty dog decided he would go to heaven and procure the seeds for his beloved masters. Back in ancient times, dogs had nine tails so when the dog got to heaven he placed his tails on the ground and many of the seeds stuck in his fur. However, while he was collecting the seeds he was spotted by a guard. Before the dog could get away, the guard managed to chop off eight of his tails. He managed to get back to earth with one of his tails still intact and he gave the seeds to his human masters, allowing them to grow grain. In other versions of the legend, the dog is replaced by an ox and this may explain why some Zhuang communities happily eat dogs.

These superstitions play a focal role in Zhuang funerals, as they believe that the souls of the deceased enter the netherworld but continue to assist the living. Ancestor worship is common and their burial rites are particularly unusual, as the dead are buried twice. The deceased is first wrapped in white cloth and, after three days, they are buried in a coffin along with a few of their favourite things. A Taoist priest or local shaman will preside over the funeral, depending on the family’s beliefs. Families will sometimes even arrange what is known as a “spirit marriage” to appease the souls of those who died unmarried!

These superstitions play a focal role in Zhuang funerals, as they believe that the souls of the deceased enter the netherworld but continue to assist the living. Ancestor worship is common and their burial rites are particularly unusual, as the dead are buried twice. The deceased is first wrapped in white cloth and, after three days, they are buried in a coffin along with a few of their favourite things. A Taoist priest or local shaman will preside over the funeral, depending on the family’s beliefs. Families will sometimes even arrange what is known as a “spirit marriage” to appease the souls of those who died unmarried!

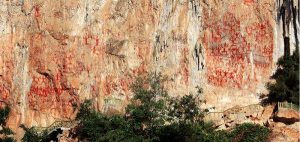

After three years, the deceased is disinterred and the bones are cleaned. They are then placed in a pottery urn and sprinkled with a red mineral called cinnabar. The urn is deposited in a cave or grotto until an appropriate burial site has been chosen in the clan cemetery. Once this has been done, the deceased is officially classed as an ancestor and can be worshipped at the ancestral shrine.

However, the Zhuang believe that anyone who died a violent, untimely or accidental death could become an evil spirit if not buried properly. They must be cremated while a local necromancer or Taoist priest chants scripture. The remains are carried over a fire pit, which the necromancer or priest must jump over! It is believed that this process “changes” the ashes from those of an evil spirit into a benevolent ancestor spirit.

Nowadays, most Mongols live in modern apartment blocks or fixed residences. However, you’ll still find plenty of Mongol people maintaining their nomadic heritage and living on the grasslands in a type of portable domed tent known as a ger or yurt. Some people even alternate between the two; living in urban housing for part of the year and then shifting to a ger in order to tend to their livestock. The use of these unusual abodes dates back to the time of the mighty Genghis Khan, roughly around about the 12th century. With their bright white exteriors and perfectly rounded shape, these magnificent gers look like glittering pearls scattered across the jade-hued grasslands.

Nowadays, most Mongols live in modern apartment blocks or fixed residences. However, you’ll still find plenty of Mongol people maintaining their nomadic heritage and living on the grasslands in a type of portable domed tent known as a ger or yurt. Some people even alternate between the two; living in urban housing for part of the year and then shifting to a ger in order to tend to their livestock. The use of these unusual abodes dates back to the time of the mighty Genghis Khan, roughly around about the 12th century. With their bright white exteriors and perfectly rounded shape, these magnificent gers look like glittering pearls scattered across the jade-hued grasslands. The customs and taboos of the Uyghur ethnic minority have been informed primarily by their rich history and their pious belief in Islam. When receiving guests, the host will typically offer them the best seats, treat them to some tea or milk, and then provide them with some small snacks, such as dried fruit or sweetmeats. If you are offered a drink, be sure to take the cup with both hands as this is a sign of courtesy. The same applies if you are being offered a gift.

The customs and taboos of the Uyghur ethnic minority have been informed primarily by their rich history and their pious belief in Islam. When receiving guests, the host will typically offer them the best seats, treat them to some tea or milk, and then provide them with some small snacks, such as dried fruit or sweetmeats. If you are offered a drink, be sure to take the cup with both hands as this is a sign of courtesy. The same applies if you are being offered a gift.

The practice of giving hada is so centric to Tibetan culture that, whenever a person leaves the house, they will carry several hada with them in case an opportunity arises where they might be expected to offer one. When writing letters, they will even enclose a miniature hada in the envelope! In most contexts, the hada is designed to extend good wishes and respect, but its significance may change slightly depending on the context. During festivals, a hada is exchanged to wish the recipient a happy holiday. At weddings, the bride and groom are presented with hada in the hopes that they will have everlasting harmony and a bright future together. At funerals, the family present hada to the guests so that the Buddha may bless them and the guests offer hada to the grieving relatives in order to express their condolences.

The practice of giving hada is so centric to Tibetan culture that, whenever a person leaves the house, they will carry several hada with them in case an opportunity arises where they might be expected to offer one. When writing letters, they will even enclose a miniature hada in the envelope! In most contexts, the hada is designed to extend good wishes and respect, but its significance may change slightly depending on the context. During festivals, a hada is exchanged to wish the recipient a happy holiday. At weddings, the bride and groom are presented with hada in the hopes that they will have everlasting harmony and a bright future together. At funerals, the family present hada to the guests so that the Buddha may bless them and the guests offer hada to the grieving relatives in order to express their condolences.

Living primarily in isolated locations throughout India, Nepal, Bhutan, and the Tibet Autonomous Region of China, the Tibetan people have maintained an air of mystery that has captured the curiosity of people throughout the world. They embody a culture defined by spirituality, communion with nature, and rigid discipline. Even their language is highly stylised, with honorific and ordinary versions for most words, which are used to address superiors or inferiors respectively. The indisputable importance that religion holds for Tibetans is reflected in this language, as there is a set of higher honorific terms that are only to be used when addressing the highest sect of Buddhist lamas.

Living primarily in isolated locations throughout India, Nepal, Bhutan, and the Tibet Autonomous Region of China, the Tibetan people have maintained an air of mystery that has captured the curiosity of people throughout the world. They embody a culture defined by spirituality, communion with nature, and rigid discipline. Even their language is highly stylised, with honorific and ordinary versions for most words, which are used to address superiors or inferiors respectively. The indisputable importance that religion holds for Tibetans is reflected in this language, as there is a set of higher honorific terms that are only to be used when addressing the highest sect of Buddhist lamas. In spite of the hostile environment in which they live, the traditional garments of the Tibetan people are defined by their bright colours and elaborate ornamentation. Like precious stones and glimmering jewels, they stand out on the barren plains of the Tibetan plateau. Tibetans typically don long-sleeved jackets made of silk or cloth, covered by a loose robe tied at the right by a band. Nomadic herdsmen and women working in colder climates eschew the jacket in favour of sheepskin robes fringed with fur. While women tend to wear skirts with a multi-coloured apron over top and men wear trousers, they both opt for leather long-boots to combat the rocky terrain and felt or fur hats to keep themselves warm. For the sake of mobility, many Tibetans leave one or both shoulders uncovered and tie the sleeves around their waist when they are working.

In spite of the hostile environment in which they live, the traditional garments of the Tibetan people are defined by their bright colours and elaborate ornamentation. Like precious stones and glimmering jewels, they stand out on the barren plains of the Tibetan plateau. Tibetans typically don long-sleeved jackets made of silk or cloth, covered by a loose robe tied at the right by a band. Nomadic herdsmen and women working in colder climates eschew the jacket in favour of sheepskin robes fringed with fur. While women tend to wear skirts with a multi-coloured apron over top and men wear trousers, they both opt for leather long-boots to combat the rocky terrain and felt or fur hats to keep themselves warm. For the sake of mobility, many Tibetans leave one or both shoulders uncovered and tie the sleeves around their waist when they are working.