Most Mongols follow a folk religion known as Mongolian shamanism, which is part of a much broader Central Asian faith called Tengrism. It combines numerous shamanistic[1] and animistic[2] elements, and is intrinsically intertwined with aspects of the Mongolian people’s tribal culture. However, during the Mongol-led Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368), Buddhism grew in popularity throughout China and soon became mingled with Mongolian shamanism, producing a new branch of the religion that is often referred to as Yellow shamanism. It is so-called because it incorporates many features from the Gelug or “Yellow Hat” sect of Tibetan Buddhism. This serves to distinguish it from another form of the religion that adamantly rejected Buddhist teachings, known by the ominous title of Black shamanism.

Generally speaking, Mongolian shamanism is centred on the worship of deities, called tngri, and the God of Heaven or ultimate deity, known as Tenger. From the 13th century onwards, Genghis Khan was elevated from legendary conqueror to godlike entity, as he is considered to be one of the embodiments of Tenger. The Mausoleum of Genghis Khan in the city of Ordos serves not only as a monument to his historical legacy, but also as a religious centre where he is worshipped.

Within the pantheon of gods, the highest group are the 99 tngri, 55 of which are benevolent or “white” and 44 of which are malevolent or “black”. These are followed by the 77 natigai or “earth-mothers”, below which are numerous other deities of various types and functions. Historically the tngri were common to all clans, and could be called upon by special individuals known as shamans (böö) and shamanesses (udgan), who acted as intercessors between the human and the spirit realm. However, under certain circumstances, clan leaders, nobles, and even commoners could interact with the spirit world.

After these core deities, there are three groups of ancestral spirits that were usually specific to a clan. The first were the “Lord Spirits”, which were the souls of previous clan leaders; the second were the “Protector Spirits”, made up of the souls of great shamans (ĵigari) and shamanesses (abĵiya); and the final group were the “Guardian Spirits”, consisting of the souls of smaller shamans (böge) and shamanesses (idugan). That being said, there was still plenty of room in the spirit realm for the little guys too!

After these core deities, there are three groups of ancestral spirits that were usually specific to a clan. The first were the “Lord Spirits”, which were the souls of previous clan leaders; the second were the “Protector Spirits”, made up of the souls of great shamans (ĵigari) and shamanesses (abĵiya); and the final group were the “Guardian Spirits”, consisting of the souls of smaller shamans (böge) and shamanesses (idugan). That being said, there was still plenty of room in the spirit realm for the little guys too!

Although they weren’t inducted as ancestral spirits, there were three further divisions of spirits that could be called upon in times of need: the white spirits of nobles from the clan; the black spirits of commoners; and the evil spirits of slaves and non-human goblins. Since delegation is as important to the spirit realm as it is to the business world, white spirits could only be called upon by white shamans and conversely black shamans were only permitted to contact black spirits. If a white shaman called on a black spirit, they would lose their right to summon white spirits, while if a black shaman dared contact a white spirit, he would be brutally punished by the black spirits.

The worshipping of these deities and spirits is primarily done at sacrificial altars known as ovoos or “magnificent shrines”. Ovoos are sacred stone heaps that are typically made from nearby rocks, wood, and strips of colourful silk. They vary in size and are often located in high places, such as at the top of mountains or within mountain passes. Each ovoo is meant to be symbolic of a deity, so there are ovoos dedicated to heavenly gods, mountain gods, gods of nature, ancestral spirits, and any otherworldly entity you could think of! Slaughtered animals, incense sticks, and libations all serve as worthy sacrifices when one is worshipping at an ovoo.

If a Mongolian person happens to pass by an ovoo while traveling, it is customary to stop and circle the ovoo three times in a clockwise direction, as it is believed this will protect them during their journey. After that, they will usually pick rocks up from the ground and add them to the pile. In some cases, they might even leave offerings in the form of candy, money, milk, or alcohol. As modernity has crept in, these traditions have had to change, and it is now considered acceptable to honk your horn while passing an ovoo if you don’t have time to stop.

If a Mongolian person happens to pass by an ovoo while traveling, it is customary to stop and circle the ovoo three times in a clockwise direction, as it is believed this will protect them during their journey. After that, they will usually pick rocks up from the ground and add them to the pile. In some cases, they might even leave offerings in the form of candy, money, milk, or alcohol. As modernity has crept in, these traditions have had to change, and it is now considered acceptable to honk your horn while passing an ovoo if you don’t have time to stop.

At the end of summer, ovoos become the site of Heaven worship ceremonies, where people gather to make offerings to Tenger. They first place a tree branch or stick into the ovoo and tie a blue ceremonial silk scarf to it, known as a khadag. This scarf is meant to symbolise the blueness of the open sky and Tenger himself, who is regarded as the sky spirit. They then light a fire and make offerings of food before taking part in ceremonial dances and prayers. Food left over from the offering ceremony becomes part of a lavish feast that is shared by all of the participants. After all, maintaining that religious fervour must really work up an appetite!

[1] Shamanism: The practice of attempting to reach altered states of consciousness in order to communicate with the spirit world and channel energy from it into the real world. This can only be done by specialist practitioners known as shaman.

[2] Animism: The belief that all non-human entities, including animals, plants, and even inanimate objects, possess a spiritual essence or soul.

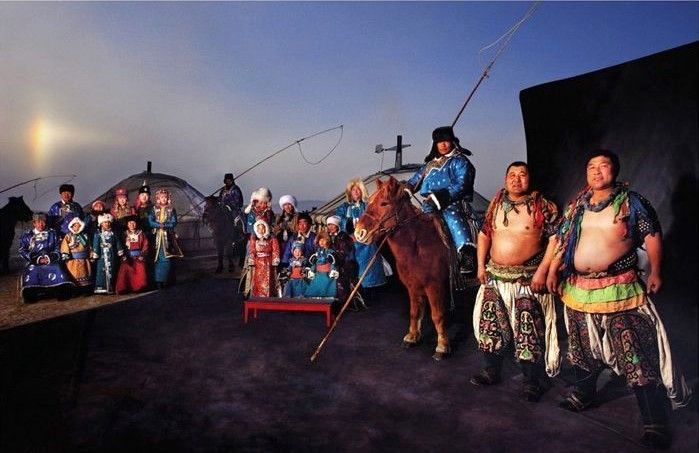

Historically, the ancestors of the Mongols were small nomadic tribes, such as the Xiongnu, the Xianbei, and the Donghu, who roamed the regions surrounding the Argun River sometime between the 5th and 3rd century BC. They remained largely separate until the beginning of the 13th century, when an enigmatic warrior loomed on the horizon and threatened to irrevocably change the course of history.

Historically, the ancestors of the Mongols were small nomadic tribes, such as the Xiongnu, the Xianbei, and the Donghu, who roamed the regions surrounding the Argun River sometime between the 5th and 3rd century BC. They remained largely separate until the beginning of the 13th century, when an enigmatic warrior loomed on the horizon and threatened to irrevocably change the course of history.

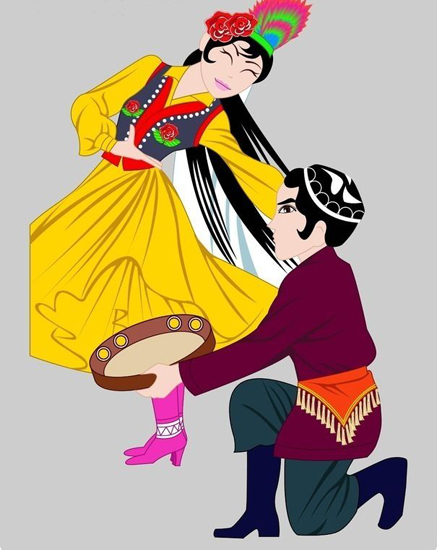

Throughout their long and illustrious history, the Uyghur people have adopted numerous religions, including shamanism

Throughout their long and illustrious history, the Uyghur people have adopted numerous religions, including shamanism

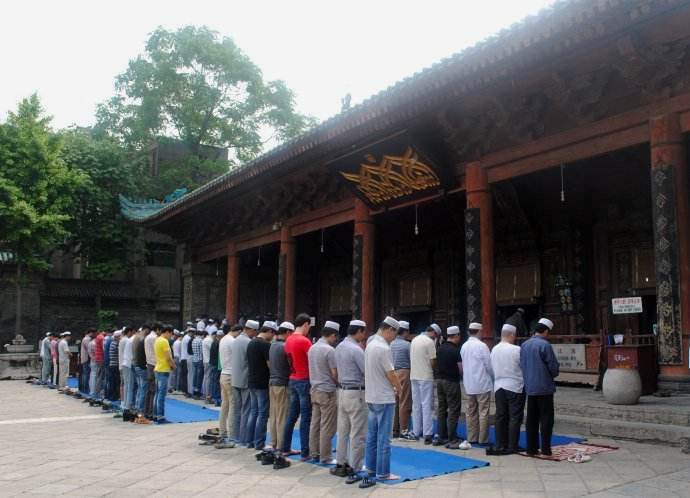

Thus the Hui people have a direct link not to China but to Central Asia. They have a varied ancestry that includes Arab, Persian, Mongol, Turkic and other Central Asian ancestors and their origins can be traced back in two ways. Some Hui people descended from Arab and Persian traders, who arrived in China via the Silk Road during the Tang Dynasty (618-907). Around the 7th century, some of them eventually settled in cities such as Guangzhou, Quanzhou, Hangzhou, Yangzhou and Chang’an (modern-day Xi’an) and were referred to as “fanke” or “guests from outlying regions”. Wherever they settled, they built mosques and public cemeteries. Over time they intermarried with Han people and converted their partners to Islam but largely assimilated with Chinese culture.

Thus the Hui people have a direct link not to China but to Central Asia. They have a varied ancestry that includes Arab, Persian, Mongol, Turkic and other Central Asian ancestors and their origins can be traced back in two ways. Some Hui people descended from Arab and Persian traders, who arrived in China via the Silk Road during the Tang Dynasty (618-907). Around the 7th century, some of them eventually settled in cities such as Guangzhou, Quanzhou, Hangzhou, Yangzhou and Chang’an (modern-day Xi’an) and were referred to as “fanke” or “guests from outlying regions”. Wherever they settled, they built mosques and public cemeteries. Over time they intermarried with Han people and converted their partners to Islam but largely assimilated with Chinese culture.