According to legend, when the first ancient pioneers set out from northern and central China in the hopes of discovering and populating southern China, they came upon a number of difficulties. In the mountainous forests of south China, they met with fierce beasts, venomous snakes, and a myriad of unpleasant insects. In spite of this adversity, they managed to settle a colony in the south and set fires around the colony in order to deter wild beasts. However, the people continued to be plagued by vicious snakes and deadly scorpions, until one of the tribal leaders, an old, wise and well-respected man, came upon an idea for a building suspended on wooden stilts. The colony built these tall dwellings and soon they were safe from the dangers of the creatures below.

These were the first diaojiaolou, a dwelling popular among several of the ethnic minority communities throughout southern China. The word “diaojiao” (吊脚) in Chinese means “hanging feet” and “lou” (楼) means “building”, so diaojiaolou literally means “hanging feet building”. They are so named because of their unusual appearance. The history of the diaojiaolou stretches back over 500 years and they are widespread throughout Yunnan, Guangxi, Hunan, Guizhou, Hubei, and Sichuan province but differ in appearance depending on the ethnic group who built them.

Diaojiaolou are rectangular or square wooden buildings built in the ganlan–style. A ganlan-style building is any building that is supported by stilts or wood columns. Diaojiaolou are typically two to three storeys high. The upper floors are held up by thick wooden stilts, which give the building an unsteady appearance. These stilts are further reinforced by stone blocks at their base, meaning diaojiaolou are in fact very stable. Even if one column is destroyed or one stone block is removed, the building will still stand firm. These buildings are a masterpiece of ingenious carpentry, as oftentimes they are made using no nails or rivets. The structure and stability of the building depends on groove joints, which hold the wooden beams and columns together perfectly.

Diaojiaolou are rectangular or square wooden buildings built in the ganlan–style. A ganlan-style building is any building that is supported by stilts or wood columns. Diaojiaolou are typically two to three storeys high. The upper floors are held up by thick wooden stilts, which give the building an unsteady appearance. These stilts are further reinforced by stone blocks at their base, meaning diaojiaolou are in fact very stable. Even if one column is destroyed or one stone block is removed, the building will still stand firm. These buildings are a masterpiece of ingenious carpentry, as oftentimes they are made using no nails or rivets. The structure and stability of the building depends on groove joints, which hold the wooden beams and columns together perfectly.

The ground floor is made up primarily of the supporting columns and often does not have any walls. This floor tends to be used as a kind of stable for livestock or as a storage space for firewood and farming equipment. The second and third floors will be used as living spaces, although occasionally the top floor will be used as an extra storage space. The top two floors will have verandas or balconies, which are used to dry clothes. Some diaojiaolou built by wealthier families will have attics or annexes to provide more space.

Although the original legend behind the diaojiaolou may seem farfetched, it touches upon one of its main benefits. The key to its popularity is that, in ancient times, these stilted buildings would provide protection from wild animals, and nowadays they continue to provide protection from venomous snakes and insects that are still prolific throughout China. The cool breeze blowing through the windows of the upper levels acts like a kind of natural air conditioner, meaning these buildings also help prevent humidity-related diseases common in southern China. In the south of China, the level of humidity on the ground during summer is almost unbearable and potentially dangerous, so elevated living spaces are particularly important. These stilted houses are also designed to survive most natural disasters, such as floods and earthquakes.

On top of these safety benefits, diaojiaolou also offer some unique benefits that help improve the quality of life for their inhabitants. Their stilted design means they can be built on mountainsides or across bodies of water, so they were often used to colonise previously uninhabitable areas of China. Since the upper floors are particularly high up, they receive more natural light than the ground floor. In the past, this allowed inhabitants to easily work on their craftwork inside and nowadays, because they are naturally well-lit, many diaojiaolou do not have electrical lighting on their upper floors. These upper floors also act as a vantage point, so farmers have a broad view from which to survey their land.

The Miao, Dong, Zhuang, Yao, Tujia, Bouyei, and Shui ethnic minorities have all incorporated diaojiaolou into their architecture and villages. Although the basic style of each diaojiaolou is the same, there are variations between those of different ethnic minorities.

- Miao Diaojiaolou

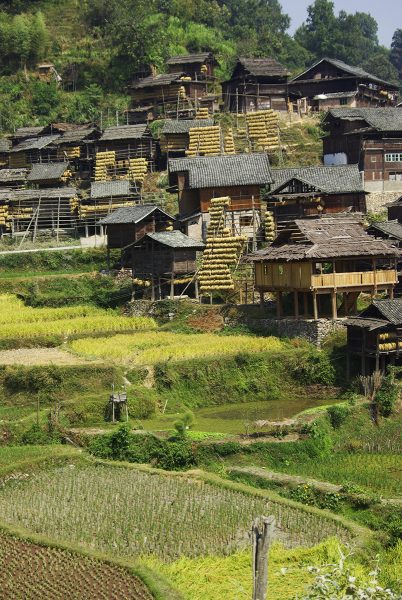

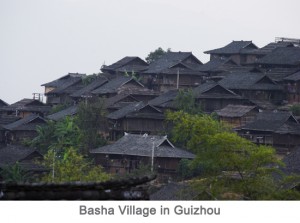

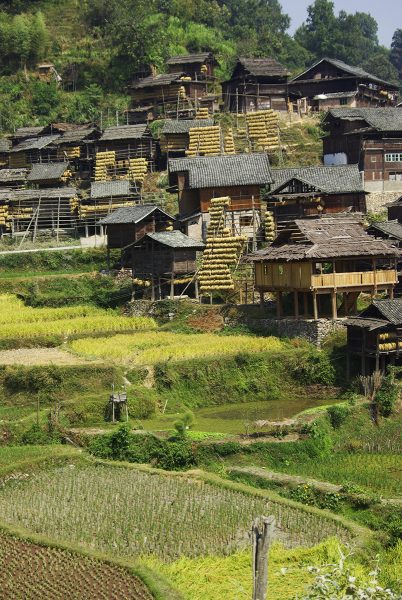

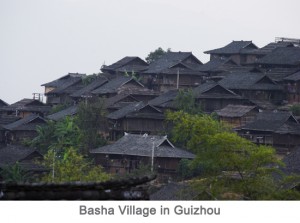

The Miao people have a reputation for living in mountainous areas and thus diaojiaolou make the perfect dwellings. Miao diaojiaolou spread up the sides of mountains and are built on very steep gradients. They are usually built by the villagers using local fir wood. The front of this type of diaojiaolou is held up by pillars but the rear of the house is suspended on wooden poles, making it level with the mountainside. This gives the Miao diaojiaolou their distinctive “hanging” appearance. The Miao villages of Basha, Xijiang and Langdeshang in Guizhou province have particularly stunning diaojiaolou. Xijiang is the largest Miao village in the world and has the widest showcase of Miao diaojiaolou.

The Miao people have a reputation for living in mountainous areas and thus diaojiaolou make the perfect dwellings. Miao diaojiaolou spread up the sides of mountains and are built on very steep gradients. They are usually built by the villagers using local fir wood. The front of this type of diaojiaolou is held up by pillars but the rear of the house is suspended on wooden poles, making it level with the mountainside. This gives the Miao diaojiaolou their distinctive “hanging” appearance. The Miao villages of Basha, Xijiang and Langdeshang in Guizhou province have particularly stunning diaojiaolou. Xijiang is the largest Miao village in the world and has the widest showcase of Miao diaojiaolou.

- Dong Diaojiaolou

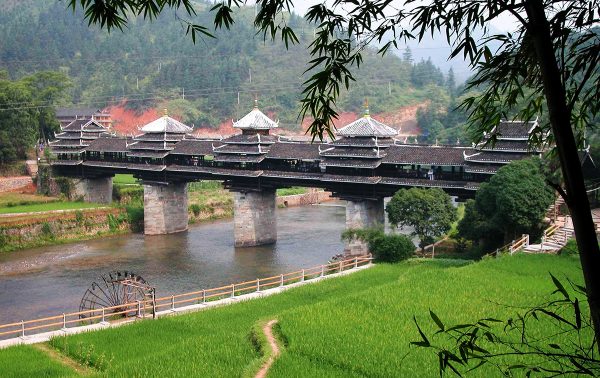

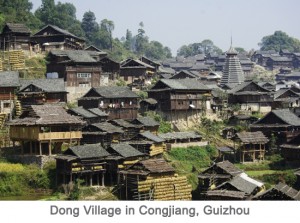

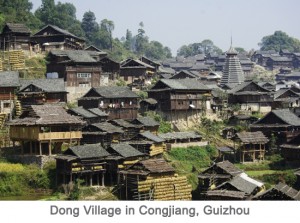

Most Dong villages are at the foot of a mountain or hill and all Dong settlements will be near to a stream or river, so stilted diaojiaolou are useful for building up the mountainside or building over the water. Since the Dong diaojiaolou are not built on a steep gradient, the “hanging” aspect of the upper floors is not as pronounced as it is in Miao diaojiaolou. Dong diaojiaolou are aesthetically magnificent, as the Dong people are skilful carpenters and love to adorn their buildings with intricate carvings of flowers, wild animals and mythical creatures. If you want to see the Dong style of diaojiaolou, we recommend visiting the villages of Zhaoxing and Xiaohuang in Guizhou province. Zhaoxing’s architecture is particularly spectacular, as it contains five Drum Towers of differing styles.

Most Dong villages are at the foot of a mountain or hill and all Dong settlements will be near to a stream or river, so stilted diaojiaolou are useful for building up the mountainside or building over the water. Since the Dong diaojiaolou are not built on a steep gradient, the “hanging” aspect of the upper floors is not as pronounced as it is in Miao diaojiaolou. Dong diaojiaolou are aesthetically magnificent, as the Dong people are skilful carpenters and love to adorn their buildings with intricate carvings of flowers, wild animals and mythical creatures. If you want to see the Dong style of diaojiaolou, we recommend visiting the villages of Zhaoxing and Xiaohuang in Guizhou province. Zhaoxing’s architecture is particularly spectacular, as it contains five Drum Towers of differing styles.

- Zhuang Diaojiaolou

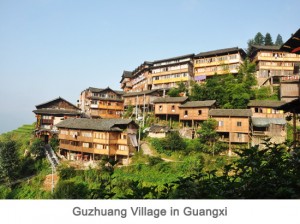

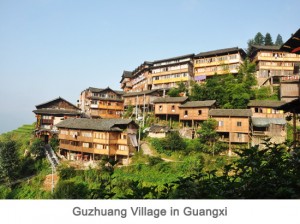

The exterior of the Zhuang diaojiaolou does not look dissimilar to that of the Dong diaojiaolou. However, the key difference is the interior, as they have a shrine at their centre which is used for ancestor worship. They also usually incorporate separate bedrooms for the husband and wife, which is an archaic Zhuang custom. The Zhuang villages of Ping’an and Guzhuang have wonderful diaojiaolou. Guzhuang village has the largest number of Zhuang diaojiaolou in China and some of these buildings date back over 100 years, making them some of the oldest diaojiaolou in the country.

The exterior of the Zhuang diaojiaolou does not look dissimilar to that of the Dong diaojiaolou. However, the key difference is the interior, as they have a shrine at their centre which is used for ancestor worship. They also usually incorporate separate bedrooms for the husband and wife, which is an archaic Zhuang custom. The Zhuang villages of Ping’an and Guzhuang have wonderful diaojiaolou. Guzhuang village has the largest number of Zhuang diaojiaolou in China and some of these buildings date back over 100 years, making them some of the oldest diaojiaolou in the country.

- Yao Diaojiaolou

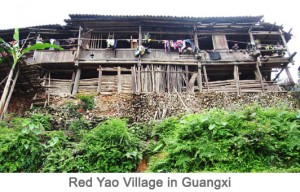

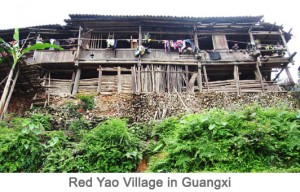

The Yao ethnic minority tend to live on flat land so Yao diaojiaolou are usually short and have wooden stilts of even heights. In some cases, the ground floor of a Yao diaojiaolou may have walls. The cluster of Yao villages near the Jinkeng Rice Terraces in Guangxi province is the perfect place to admire this style of diaojiaolou. One of these villages, known as Dazhai, even has some diaojiaolou that now function as hotels!

The Yao ethnic minority tend to live on flat land so Yao diaojiaolou are usually short and have wooden stilts of even heights. In some cases, the ground floor of a Yao diaojiaolou may have walls. The cluster of Yao villages near the Jinkeng Rice Terraces in Guangxi province is the perfect place to admire this style of diaojiaolou. One of these villages, known as Dazhai, even has some diaojiaolou that now function as hotels!

- Tujia Diaojiaolou

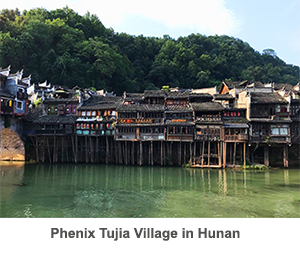

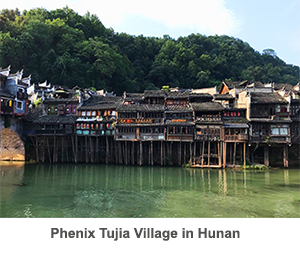

In contrast to the Miao people, the Tujia people prefer to live near mountains but close to or sometimes even over rivers or streams. Thus you’ll find that many Tujia diaojiaolou are either placed directly on the waterfront or hang over the water. The Tujia believe that these stilted houses embody the coexistence of God and man, so the designs of their diaojiaolou often reflect this. Tujia diaojiaolou are hard to come by, since the Tujia people are slowly abandoning their old settlements and assimilating into modern Chinese culture. The Tujia Folk Customs Park in Zhangjiajie, Hunan, is a large scale replica of a traditional Tujia village and features Tujia style Diaojiaolou. However, if you want a more authentic experience, we recommend visiting the Tujia village of Shuitianba in the Enshi Tujia and Miao Autonomous Prefecture of Hubei Province.

In contrast to the Miao people, the Tujia people prefer to live near mountains but close to or sometimes even over rivers or streams. Thus you’ll find that many Tujia diaojiaolou are either placed directly on the waterfront or hang over the water. The Tujia believe that these stilted houses embody the coexistence of God and man, so the designs of their diaojiaolou often reflect this. Tujia diaojiaolou are hard to come by, since the Tujia people are slowly abandoning their old settlements and assimilating into modern Chinese culture. The Tujia Folk Customs Park in Zhangjiajie, Hunan, is a large scale replica of a traditional Tujia village and features Tujia style Diaojiaolou. However, if you want a more authentic experience, we recommend visiting the Tujia village of Shuitianba in the Enshi Tujia and Miao Autonomous Prefecture of Hubei Province.

- Bouyei Diaojiaolou

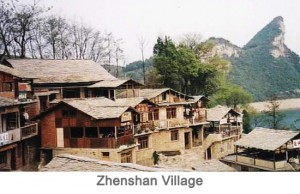

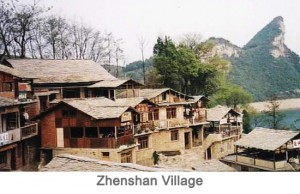

The Bouyei people are renowned more for their unique stone houses than for their diaojiaolou. Their diaojiaolou, though no less magnificent, are relatively typical and have few distinguishing features. The fame of the Bouyei stone buildings has tragically overshadowed their diaojiaolou and thus Bouyei diaojiaolou are difficult to find. Located about 21 kilometres away from the city of Guiyang, Zhenshan village in Guizhou province has a mixed community of Bouyei and Miao people, with Bouyei making up about 75% of its population. Though most of the buildings in Zhenshan are made of stone, a few are made of both wood and stone in the diaojiaolou style. Alternatively, some of the Bouyei villages near the Nanpan River in Yunnan province contain several diaojiaolou.

The Bouyei people are renowned more for their unique stone houses than for their diaojiaolou. Their diaojiaolou, though no less magnificent, are relatively typical and have few distinguishing features. The fame of the Bouyei stone buildings has tragically overshadowed their diaojiaolou and thus Bouyei diaojiaolou are difficult to find. Located about 21 kilometres away from the city of Guiyang, Zhenshan village in Guizhou province has a mixed community of Bouyei and Miao people, with Bouyei making up about 75% of its population. Though most of the buildings in Zhenshan are made of stone, a few are made of both wood and stone in the diaojiaolou style. Alternatively, some of the Bouyei villages near the Nanpan River in Yunnan province contain several diaojiaolou.

- Shui Diaojiaolou

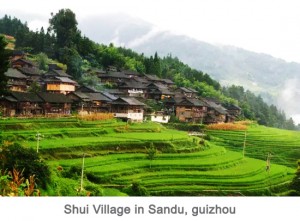

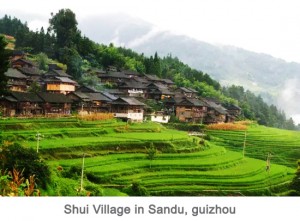

The Shui dwellings are not typical diaojiaolou and so are often referred to as “woodpile dwellings”. This is because the stilts on the ground level are very short and the ground level will usually have walls, meaning the house looks kind of like a woodpile. Shui diaojiaolou will only ever have an odd number of rooms, since there is a taboo on even numbers in Shui culture. There are some small Shui villages in Guizhou province is the perfect place to admire these quaint little “woodpiles”.

The Shui dwellings are not typical diaojiaolou and so are often referred to as “woodpile dwellings”. This is because the stilts on the ground level are very short and the ground level will usually have walls, meaning the house looks kind of like a woodpile. Shui diaojiaolou will only ever have an odd number of rooms, since there is a taboo on even numbers in Shui culture. There are some small Shui villages in Guizhou province is the perfect place to admire these quaint little “woodpiles”.

Join a tour with us to explore more about Diaojiaolou: Explore the Culture of Ethnic Minorities in Guizhou

A propitious day will then be chosen to erect the house and one month before this day a carpenter will prepare the house’s structure. When the day finally comes, a sacrifice will be made to Lu Ban, the God of Carpentry. The main beam, which is decorated with red silk, will then be carried from the father-in-law’s house to the building site and accompanied by an orchestra, as well as a team of acrobats. In other words, this beam gets a grander entrance than most celebrities! Once the beam has been fixed, a singing and dancing ceremony will take place, followed by a feast. After the festivities, a shrine dedicated to the family’s ancestors and the Kitchen God will be positioned in a central part of the new house.

A propitious day will then be chosen to erect the house and one month before this day a carpenter will prepare the house’s structure. When the day finally comes, a sacrifice will be made to Lu Ban, the God of Carpentry. The main beam, which is decorated with red silk, will then be carried from the father-in-law’s house to the building site and accompanied by an orchestra, as well as a team of acrobats. In other words, this beam gets a grander entrance than most celebrities! Once the beam has been fixed, a singing and dancing ceremony will take place, followed by a feast. After the festivities, a shrine dedicated to the family’s ancestors and the Kitchen God will be positioned in a central part of the new house. Funerals in Bouyei communities are notoriously complicated procedures. Once a person has died, their relatives bath them, comb their hair, and dress them. The corpse is then placed on a bed, where friends and relatives can pay their last respects. The funeral begins with a priest performing a ritual where he asks the dragon to help the deceased’s soul on its way to the underworld. Then a bull is slaughtered and its meat is shared by everyone except relatives of the deceased. The Bouyei believe that this bull will help the soul of the deceased plough fields in the underworld, although we dread to think what kinds of crops they grow down there!

Funerals in Bouyei communities are notoriously complicated procedures. Once a person has died, their relatives bath them, comb their hair, and dress them. The corpse is then placed on a bed, where friends and relatives can pay their last respects. The funeral begins with a priest performing a ritual where he asks the dragon to help the deceased’s soul on its way to the underworld. Then a bull is slaughtered and its meat is shared by everyone except relatives of the deceased. The Bouyei believe that this bull will help the soul of the deceased plough fields in the underworld, although we dread to think what kinds of crops they grow down there!

In contrast to the Miao people, the Tujia people prefer to live near mountains but close to or sometimes even over rivers or streams. Thus you’ll find that many Tujia diaojiaolou are either placed directly on the waterfront or hang over the water. The Tujia believe that these stilted houses embody the coexistence of God and man, so the designs of their diaojiaolou often reflect this. Tujia diaojiaolou are hard to come by, since the Tujia people are slowly abandoning their old settlements and assimilating into modern Chinese culture. The Tujia Folk Customs Park in Zhangjiajie, Hunan, is a large scale replica of a traditional Tujia village and features Tujia style Diaojiaolou. However, if you want a more authentic experience, we recommend visiting the Tujia village of Shuitianba in the Enshi Tujia and Miao Autonomous Prefecture of Hubei Province.

In contrast to the Miao people, the Tujia people prefer to live near mountains but close to or sometimes even over rivers or streams. Thus you’ll find that many Tujia diaojiaolou are either placed directly on the waterfront or hang over the water. The Tujia believe that these stilted houses embody the coexistence of God and man, so the designs of their diaojiaolou often reflect this. Tujia diaojiaolou are hard to come by, since the Tujia people are slowly abandoning their old settlements and assimilating into modern Chinese culture. The Tujia Folk Customs Park in Zhangjiajie, Hunan, is a large scale replica of a traditional Tujia village and features Tujia style Diaojiaolou. However, if you want a more authentic experience, we recommend visiting the Tujia village of Shuitianba in the Enshi Tujia and Miao Autonomous Prefecture of Hubei Province.